Our Man in Tehran (Taylor and Weinstein, 2013)

Our Man in Tehran releases on DVD this week over at First Run Features. My review initially ran at Christianity Today Movies & TV as part of a report on the 2014 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival. All rights reserved.

—

There is a moment in Our Man in Tehran, Drew Taylor’s and Larry Weinstein’s documentary about “the Iranian hostage crisis and Canada’s role in it,” when former hostage William Daugherty describes being tortured. His hands were bound together with wire to cut off the circulation and make them more sensitive and then beaten with a hose. Daugherty calls it the worst, most excruciating pain he has ever felt.

There is something humbling and haunting about approaching another human being in the place where he has been hurt the worst. An action as perfunctory as a handshake before or after an interview can remind you of how much power—to cause pain or to promote healing—there is in the human touch, how words and deeds have consequences that will be felt for years.

History is comprised of human lives, and one of the things that made Our Man in Tehran a highlight of the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival (held April 3-6 in Durham, North Carolina) was that while the personal narratives provided context for the broader historical narrative, they were never eclipsed by it. Co-director Larry Weinstein said he tries to shy away from voice-over narration partly because it can come across as spoon-feeding history. He prefers to let his film’s subjects talk directly to the audience—and they do.

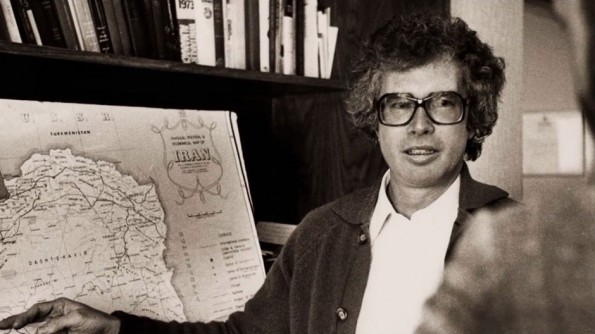

The “Man” of the title is Ken Taylor, the former Canadian ambassador to Iran who risked his own life and those of his countrymen to help six Americans who had fled the fallen embassy get out of Iran. Co-director Drew Taylor (no relation to Ken Taylor) told me the film was in the works before Argo and was categorically not meant as any kind of response to Ben Affleck’s film or attempt to capitalize on it.

The documentary was made because the hostage crisis was “a very important moment in Canadian history,” and also because the reticence of many who lived through the events, including Ken Taylor, meant that despite the great amount of archival news footage there were facts about the story that were not widely known. Among them are that Taylor helped the United States gather information to prepare for Operation Eagle Claw, and that Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark and Foreign Minister Flora MacDonald approved the historically unprecedented step of issuing passports for non-citizens which were handed over to the American government (and eventually used in operation Argo).

The remarkable thing about Our Man in Tehran is its ability (much like Rory Kennedy’s Last Days in Vietnam which also played at the festival) to take a complex situation and distill it without being reductive. The Americans first called John Sheardown, who in turn informed Ambassador Ken Taylor that he had accepted his American colleagues into his home. In an understated but remarkable scene, Taylor relates that rather than asking for permission before making a decision with international policy implications, he informed his Foreign Minister and Prime Minister of what he had done after the fact.

As Weinstein emphasized in an interview with me, Taylor, Sheardown, Clark, and MacDonald all speak of their actions as though they were neither particularly heroic nor exceptional. They simply asked, “What’s the right thing to do?” Integral to understanding the event and why it unfolded the way it did, Weinstein suggested, is that Prime Minister Joe Clark and President Jimmy Carter “were both highly moral men.” His directing partner, Drew Taylor, concurs, saying the film depicts people making “moral decisions” and using their “basic instincts” about right and wrong to guide their decision making.

During a panel discussion with the audience, former Ambassador Ken Taylor was asked if, in retrospect, he agreed with American decision to admit the Shah of Iran to the United States for medical treatment, an act which ended up being a catalyst for the hostage crisis. He said the act “reflected a U.S. value” and that if asked he would have encouraged the United States to “take him in.”

That answer provided important insight into the motivations of the participants. It was tempting while watching the film or interviewing the artists to wonder if such a value-driven form of decision making was specific to the time period or to Canada, because seeing people act in such a way challenges the viewers’ cynicism about politicians and statesmen.

When I asked Drew Taylor and Larry Weinstein if they shared my sense of wonder at that part of the story, they both said “no.” There are ample examples in our history and in our present of people—including but not limited to religious people—choosing to put others before themselves, choosing to do what they believe is right rather than what they know is safe. Our Man in Tehran provides several examples, and for that reason is an inspirational and encouraging film.