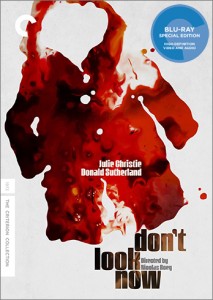

The Criterion Collection: Don’t Look Now

Ken’s Note: As most cinephiles could tell you, July is one of the month that The Criterion Collection offers its semi-annual 50% off sale. Given the label’s array of titles, taking advantage of that sale can be daunting. I’ve asked friends and colleagues to make write up one of their favorite or newly acquired Criterion discs. First up is Evan Cogswell:

—

Don’t Look Now (★★★★½) is one of the rarest types of films. Not only is it an unnerving thriller saturated with supernatural themes concerning grief, deceptive appearances, ESP, and acceptance of death, but it is also one of the few films to improve on its excellent source material, the 1971 short story of the same title by Daphne du Maurier.

The film is a pretty faithful, if slightly fleshed out, adaptation of du Maurier’s short story about a British couple staying in Venice after the death of their young daughter, Christine (Sharon Williams). While there, the wife Laura (Julie Christie) befriends two sisters (Hilary Mason and Clelia Matania), the first of whom is blind and claims to have second sight. She informs Laura that Christine is with them and warns them to leave Venice, much to the skepticism of Laura’s husband, John (Donald Sutherland). Both the film and the story are infused with an aura of dread and mystery, but the film heightens that aura through its masterful use of color schemes, cinematography, and editing.

In the new Criterion release from this past February, Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 horror film looks absolutely gorgeous. The Blu-ray transfer highlights Roeg’s decision to use almost no red at all in the sets and costumes, other than the little girl’s raincoats worn by Christine when she drowns and by the child John chases through the streets of Venice. According to a critical essay by David Thompson included with the Criterion release, the use of red was Roeg’s idea. However, it was so effective that in a 1987 republishing of the short story with watercolor illustrations by Michael Foreman, the red raincoat was reused.

The opening shots of the film bring the tragedy and horror to the center. The camera zooms in on rain falling on a pond, drawing the viewer’s attention to the water which will drown Christine and the water which will surround John and Laura in Venice as they cope with Christine’s death. Following the close-up of the pond, the film dissolves to the darkened interior of a church, suggesting the air of supernatural mystery which haunts John and Laura. The next scene develops Roeg’s use of red. As John examines a photo of a church with a girl in a red coat sitting in a pew, he spills a glass of water on it, and a close-up of the photo reveals the red ink bleeding over the photo. Simultaneously, Christine falls into a pond and drowns, clearly connecting the color red to danger.

The brilliant editing by Graeme Clifford brings all the themes together in an eerie atmospheric film. The juxtaposition of certain images and the cross cutting between scenes weave parallels throughout the film that are not found in the more linear written presentation of the story. Clifford and Roeg’s choice to alternate the shots of young Christine happily running in a bright red raincoat before she drowns with the shots of John chasing the child in a bright red raincoat by the Venetian canals adds unity to the film, gives credence to the supernatural visions of the blind sister, and makes the final reveal all the more tragic and shocking. Additionally, the chronological jumping adds a sense of uncertainty to the film, making the sense of horror and tragedy more overwhelming.

As the British couple who have suffered the death of their daughter, Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie are very convincing in their portrayal of a couple deeply in love, yet suffering from grief. Those mixed emotions come to a climax in a frequently discussed scene in which John and Laura renew their marital union. Underscored by the same music which accompanied Christine’s carefree playing before her death, and intercut with shots of them getting dressed afterward, the portrayal is one of a couple deeply in love trying to normalize their lives after a tragedy. An interview with Roeg which is included on the Criterion blu-ray reveals that Daphne du Maurier, upon seeing the film, sent Roeg a letter complimenting him on the casting of Sutherland and Christie, specifically praising the way they portrayed the troubled couple in love that she created.

As part of the Criterion edition of Don’t Look Now, interviews with Roeg, Sutherland, Christie, editor Graeme Clifford, cinematographer Anthony Richmond, co-screenwriter Allan Scott, and composer Pino Donaggio are all included as bonus features, a couple of which have a red-hooded figure in the background as a reference to the film. A major focus of several interviews is Clifford’s editing, which he believes is the best of his career, and considering how his superb editing makes Don’t Look Now as good as it is, it is difficult to argue with that sentiment. Another topic of the interviews is Roeg’s interest in what he considers a major theme of the movie: nothing is what it seems.

That theme is highlighted by the carefully controlled editing by which Roeg and Clifford manipulate what the viewer sees and does not see, and it is even referenced by the title, which appears in quotes during the opening credits. John selectively looks at what he sees, unaware of anything beyond the ordinary. Sutherland reveals in his interview that he initially did not care for the ending of the film. What he possibly failed to realize was that his character is too caught up with remembering the past and not looking at what is before him.

The Criterion release of Don’t Look Now preserves the beauty of Roeg’s film, and the bonus features provide worthwhile insight into the process of adapting du Maurier’s short story. The detail that went into Roeg’s presentation of this supernatural, grief-ridden story is incredible, and knowing that detail makes the film even more rewarding.

—

Evan Cogswell blogs about film at Catholic Cinephile.