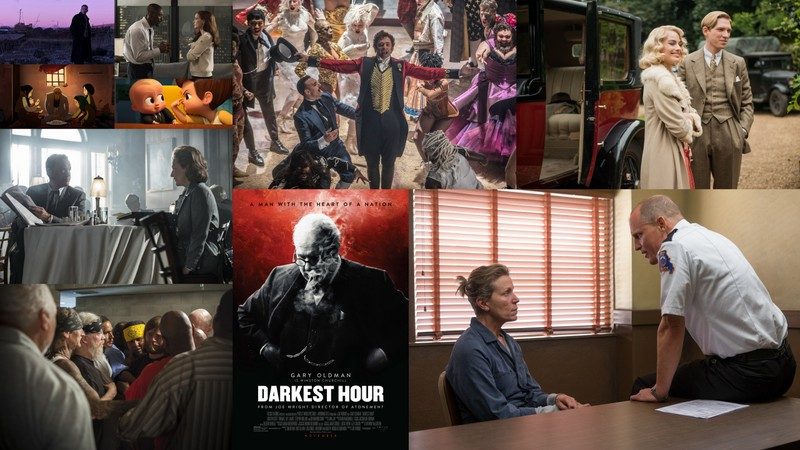

2017 Top 10

Choosing to list my favorite film experiences of the year rather than making some formal, aesthetic claim about which were the best films made my life a little easier in 2017, even if doing so invites push back.

The truth is, excepting for one film (which didn’t even get a wide release and is more likely to get consideration from others in 2018), I am sympathetic to the critiques of every entry on this list. That may make my praise sound muted and my compliments backhanded. For much of the year, that was how I felt about my favorites. But then I realized that in many cases, I loved these films not in spite of their flaws, but because of them.

In America, a contentious election in 2016 gave way to a divided and disgusted country in 2017. The #metoo trend has underlined that art is a reflection of the society it critiques and shapes, not always and only a diversion and distraction from it.

I won’t say that I don’t value art that reinforces my political ideology because we all do. But I value art that demands, seduces, or prods me to think again. Sometimes that means reassessing what I think I already know. At other times that means challenging me to articulate the truths I hold dear in a manner that is more compassionate, empathetic, or humble. The motto of this blog is “Inconspicuously Christian,” so I would like to think that a pursuit and love of truth — even when that truth isn’t pretty or pleasant — is what makes my heart skip a beat and keeps me coming back to the theater.

10) The Boss Baby — Tom McGrath

I commented on a discussion board I frequent, my tongue only half in cheek, that The Boss Baby was a better version of Darren Aronofsky’s Mother! Here the parents (rather than the husband) allegorically stand in for God, whose baffling preference for the latest household invaders prompt both an existential and practical crisis in the one who previously assumed a privileged status. If I prefer — fart jokes and all — Dreamworks’s unfairly maligned heartstring puller, it’s in part because elder sibling Tim kinda figures out on his own that love is not a zero-sum game rather than just taking that lesson as gospel from some higher authority. Also — and the film is intentional if not overt in this theme — we get to see that the Boss Baby is warped in large part due to the withholding of the very thing that Tim wants to keep for himself: nurturing love. His fear of puppies is Tim’s own existential fear writ large, showing that all God’s children struggle with same primal anxieties. God love us all equally…but me just a little more. “O Master, let me not seek as much to be consoled as to console, to be understood as to understand, to be loved as to love.”

I commented on a discussion board I frequent, my tongue only half in cheek, that The Boss Baby was a better version of Darren Aronofsky’s Mother! Here the parents (rather than the husband) allegorically stand in for God, whose baffling preference for the latest household invaders prompt both an existential and practical crisis in the one who previously assumed a privileged status. If I prefer — fart jokes and all — Dreamworks’s unfairly maligned heartstring puller, it’s in part because elder sibling Tim kinda figures out on his own that love is not a zero-sum game rather than just taking that lesson as gospel from some higher authority. Also — and the film is intentional if not overt in this theme — we get to see that the Boss Baby is warped in large part due to the withholding of the very thing that Tim wants to keep for himself: nurturing love. His fear of puppies is Tim’s own existential fear writ large, showing that all God’s children struggle with same primal anxieties. God love us all equally…but me just a little more. “O Master, let me not seek as much to be consoled as to console, to be understood as to understand, to be loved as to love.”

9) The Work — Jairus McLeary and Gethin Aldous

Those who are most traumatized, victimized, and abused, the ones with the deepest psychological and spiritual scars, are often the most allergic to bullshit. Deep pain can make us ruthlessly pragmatic; it can also free us from the layers of self-protection that too often keep us from probing, cleansing, and healing our deepest wounds. The Work is about a four day intensive, inmate-led, group therapy session at Folsom Prison. If you’ve been conned by a habitual sinner, hurt by an addict or ingrained abuser, or victimized by a violent criminal, I will excuse you for approaching these men with a high degree of suspicion and cynicism. Yet as the program and the film mix the therapy experiences of the inmates and the civilian volunteers, you might actually stop looking at them as a class — inmates — and start seeing them as individuals. Dark Cloud. Vegas. Kiki. In an astounding epilogue, the film claims that no inmate who has gone through the program and been subsequently paroled has returned. Is transformation possible? My religion says it is. It also claims that we are all made in the image of God, so the things I have in common with these men may be just as important — may be more important — than the differences that have helped propel us down different paths. My review at Christianity Today Movies & TV.

Those who are most traumatized, victimized, and abused, the ones with the deepest psychological and spiritual scars, are often the most allergic to bullshit. Deep pain can make us ruthlessly pragmatic; it can also free us from the layers of self-protection that too often keep us from probing, cleansing, and healing our deepest wounds. The Work is about a four day intensive, inmate-led, group therapy session at Folsom Prison. If you’ve been conned by a habitual sinner, hurt by an addict or ingrained abuser, or victimized by a violent criminal, I will excuse you for approaching these men with a high degree of suspicion and cynicism. Yet as the program and the film mix the therapy experiences of the inmates and the civilian volunteers, you might actually stop looking at them as a class — inmates — and start seeing them as individuals. Dark Cloud. Vegas. Kiki. In an astounding epilogue, the film claims that no inmate who has gone through the program and been subsequently paroled has returned. Is transformation possible? My religion says it is. It also claims that we are all made in the image of God, so the things I have in common with these men may be just as important — may be more important — than the differences that have helped propel us down different paths. My review at Christianity Today Movies & TV.

8) Goodbye Christopher Robin — Simon Curtis

During awards season, there seems to have been a push to get Margot Robbie recognition for I, Tonya. My response has been, “Right actress, wrong movie.” Robbie’s supporting turn as the depressed wife of the shell-shocked A.A. Milne elevates and complicates what would otherwise be a fairly conventional biopic. What fascinated me about Christopher Robin is the way it depicted various forms of depression and confronted us (or me) with the fact that we are socially and culturally far more tolerant and sympathetic of some rather than others. When someone who entertained us dies and we find out he struggled with depression, there is usually far more sympathy than understanding. That the cycle continues suggests that there are a far deeper connection than we care to admit between the individual human need for love and acceptance and corporate human stinginess in granting those things only to those who entertain us. Ken’s review at Christianity Today Movies & TV.

7) The Breadwinner – Nora Twomey

The Breadwinner is about a woman’s experience in a land so pervasively and horrifically misogynistic that it is frankly hard to watch at times. Yet it is also a film that is sympathetic to the men caught in that environment. An Afghan girl must disguise herself as a boy in order to buy bread when her father is imprisoned by the Taliban. Our collective memories and attention spans are dangerously short these days, and one of our most common errors is to assume the worst aspects of life are as they have always been…and hence, unsolvable. The father here tells his daughter that he remembers living in a time of peace. Like the flashbacks in Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, those memories are intensely painful. But we understand why the characters cling to them; they are the last, tenuous tethers to our assurance that what we are living through right now is not normal, much less inevitable. Memories of happier, healthier, and juster times are the greatest defense against despair and, hence, tyranny. And we are never more than one generation away from losing them.

The Breadwinner is about a woman’s experience in a land so pervasively and horrifically misogynistic that it is frankly hard to watch at times. Yet it is also a film that is sympathetic to the men caught in that environment. An Afghan girl must disguise herself as a boy in order to buy bread when her father is imprisoned by the Taliban. Our collective memories and attention spans are dangerously short these days, and one of our most common errors is to assume the worst aspects of life are as they have always been…and hence, unsolvable. The father here tells his daughter that he remembers living in a time of peace. Like the flashbacks in Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale, those memories are intensely painful. But we understand why the characters cling to them; they are the last, tenuous tethers to our assurance that what we are living through right now is not normal, much less inevitable. Memories of happier, healthier, and juster times are the greatest defense against despair and, hence, tyranny. And we are never more than one generation away from losing them.

6) The Greatest Showman — Michael Gracey

There is joy here, which is in precious short supply at the movies these days. But there is also a fascinating tension between the simple Romantic assertion of self in “This is Me” and the recognition of the God-shaped holes in our souls in “Never Enough.” As is most clearly articulated in Ecclesiastes, we try to fill that hole with fame, money, pleasure, family…you name it. All human work is for the mouth, yet the soul is not satisfied. Some may expect or even want Barnum to be something he is not. He collects the Oddities and just as quickly exploits them, revealing his own embarrassment and disgust. Take your pick: his early treatment of Tom Thumb and Lettie Lutz is pure humbug, or it is a sincere but weak assertion of his truest, deepest self. Either way, it is significant that “This is Me” is their song, not his, and it is prompted by his rejection of them rather than being an anthem he teaches them to sing. Barnum’s experience is more thematically linked to Jenny Lind’s aria, and in a magical way, the tension between the two songs makes both immensely more poignant. Take your pick: “From Now On” is the vacuous promise of addicts and narcissists whose moral resolve will eventually crumble in the face of the next test, or it is growing (yet still weak) assertion, prompted by the grace of the Oddities, of our collective best selves, longing, even more than it longs for success or happiness, to be better than we are today.

There is joy here, which is in precious short supply at the movies these days. But there is also a fascinating tension between the simple Romantic assertion of self in “This is Me” and the recognition of the God-shaped holes in our souls in “Never Enough.” As is most clearly articulated in Ecclesiastes, we try to fill that hole with fame, money, pleasure, family…you name it. All human work is for the mouth, yet the soul is not satisfied. Some may expect or even want Barnum to be something he is not. He collects the Oddities and just as quickly exploits them, revealing his own embarrassment and disgust. Take your pick: his early treatment of Tom Thumb and Lettie Lutz is pure humbug, or it is a sincere but weak assertion of his truest, deepest self. Either way, it is significant that “This is Me” is their song, not his, and it is prompted by his rejection of them rather than being an anthem he teaches them to sing. Barnum’s experience is more thematically linked to Jenny Lind’s aria, and in a magical way, the tension between the two songs makes both immensely more poignant. Take your pick: “From Now On” is the vacuous promise of addicts and narcissists whose moral resolve will eventually crumble in the face of the next test, or it is growing (yet still weak) assertion, prompted by the grace of the Oddities, of our collective best selves, longing, even more than it longs for success or happiness, to be better than we are today.

5) Darkest Hour — Joe Wright

I don’t set out to be deliberately contrarian even if one of my go-to maxims is “Nobody ever gained a reputation as a film critic by shouting ‘me too!'” I know I am not the only movie critic in the world who preferred Joe Wright’s Churchill portrait to Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk. It just feels that way at times. Aside from Gary Oldman’s remarkably fresh performance, the thing that impressed me the most here is that Darkest Hour made me feel like the outcome was in doubt in a way that Dunkirk never did. That’s not to downplay Nolan’s achievement. I esteemed Dunkirk, and for much of the year, it hovered in and around my Top 10. I am also not unsympathetic to those who might be put off by attempts to appropriate the film and/or Churchill’s legacy. The irony of that fact is that this film, at least as I see it, is hardly a valentine to Churchill. His stubbornness and refusal to compromise make him not all that different his peers; he just happens to be right. And by right I don’t even necessarily mean right about Hitler. Right about the need to listen to the population he is leading. Right that one can only exercise true authority by earning the consent of the governed rather than imposing one’s will on them.

I don’t set out to be deliberately contrarian even if one of my go-to maxims is “Nobody ever gained a reputation as a film critic by shouting ‘me too!'” I know I am not the only movie critic in the world who preferred Joe Wright’s Churchill portrait to Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk. It just feels that way at times. Aside from Gary Oldman’s remarkably fresh performance, the thing that impressed me the most here is that Darkest Hour made me feel like the outcome was in doubt in a way that Dunkirk never did. That’s not to downplay Nolan’s achievement. I esteemed Dunkirk, and for much of the year, it hovered in and around my Top 10. I am also not unsympathetic to those who might be put off by attempts to appropriate the film and/or Churchill’s legacy. The irony of that fact is that this film, at least as I see it, is hardly a valentine to Churchill. His stubbornness and refusal to compromise make him not all that different his peers; he just happens to be right. And by right I don’t even necessarily mean right about Hitler. Right about the need to listen to the population he is leading. Right that one can only exercise true authority by earning the consent of the governed rather than imposing one’s will on them.

4) The Post — Steven Spielberg

Nothing quite screams status quo like Spielberg, Hanks, and Streep. And did I mention that no critic ever made a reputation by saying, “me too”? I think that can lead to a market overcorrection and a devaluing of what is a conventional but superbly executed tale. Once the DVD is out, I hope to do a 3 Screenshots column to make a small contribution to the defense. There is nothing wrong with liking direction that is a bit showier, but I also like the way Spielberg’s screen compositions promote the film’s themes without always calling attention to themselves. Yes, the script can be on the nose at times. We get at least three different speeches framing Kay’s dilemma. But when the decisive moment comes, everything has to be communicated by Kay’s face rather than her words, and in that moment Streep delivers like Kirk Gibson in the World Series. As I said a few years ago with Two Days, One Night, sometimes you do know what you’ve got before it’s gone. Let us resolve to enjoy Spielberg, Hanks, and Streep while we have them.

Nothing quite screams status quo like Spielberg, Hanks, and Streep. And did I mention that no critic ever made a reputation by saying, “me too”? I think that can lead to a market overcorrection and a devaluing of what is a conventional but superbly executed tale. Once the DVD is out, I hope to do a 3 Screenshots column to make a small contribution to the defense. There is nothing wrong with liking direction that is a bit showier, but I also like the way Spielberg’s screen compositions promote the film’s themes without always calling attention to themselves. Yes, the script can be on the nose at times. We get at least three different speeches framing Kay’s dilemma. But when the decisive moment comes, everything has to be communicated by Kay’s face rather than her words, and in that moment Streep delivers like Kirk Gibson in the World Series. As I said a few years ago with Two Days, One Night, sometimes you do know what you’ve got before it’s gone. Let us resolve to enjoy Spielberg, Hanks, and Streep while we have them.

3) Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri — Neal McDonagh

We think we are so clever. Okay, I think I’m so clever. We complain about it, but there is a secret joy to being smarter than a movie and knowing exactly where it is going before it gets there. There’s an even greater joy in being wrong. Three Billboards is one of those rare gems where at least a dozen scenes end very differently than I anticipated. That’s a sign of brilliant writing, especially in a film about the very real emotional, physical, and (yes) spiritual dangers of being surer of ourselves than we have cause to be. I don’t believe in perfect movies, but I do believe in perfect scenes, and Three Billboards is one of three films that come quickly to mind when I’m asked to name a film that has a perfect ending. (The other two are Two Days, One Night and The Purple Rose of Cairo.) What starts out threatening to be a facile and card-stacked depiction of righteous anger against evil sloth gradually turns into a horror story, like The Godfather, of how easy it is to become the thing we swore we would never be. Hey did I just compare Three Billboards to three of my favorite films of all time? Yes, it’s that good.

We think we are so clever. Okay, I think I’m so clever. We complain about it, but there is a secret joy to being smarter than a movie and knowing exactly where it is going before it gets there. There’s an even greater joy in being wrong. Three Billboards is one of those rare gems where at least a dozen scenes end very differently than I anticipated. That’s a sign of brilliant writing, especially in a film about the very real emotional, physical, and (yes) spiritual dangers of being surer of ourselves than we have cause to be. I don’t believe in perfect movies, but I do believe in perfect scenes, and Three Billboards is one of three films that come quickly to mind when I’m asked to name a film that has a perfect ending. (The other two are Two Days, One Night and The Purple Rose of Cairo.) What starts out threatening to be a facile and card-stacked depiction of righteous anger against evil sloth gradually turns into a horror story, like The Godfather, of how easy it is to become the thing we swore we would never be. Hey did I just compare Three Billboards to three of my favorite films of all time? Yes, it’s that good.

2) Molly’s Game — Aaron Sorkin

Other films on this list are probably aesthetically better, but if I had to pick one to rewatch right now, I would go back to Molly’s Game. Sorkin’s writing is virtuoso good, and the pleasure of hearing it delivered by Chastain and Elba, each seemingly at the peak of their craft, is considerable. Beyond stylistic preferences, it is not lost on me that many of the films on this list — Goodbye Christopher Robin, Three Billboards, The Greatest Showman, The Post — are incidentally or primarily about women trying to survive in male-dominated environments that are downright hostile towards them. In that sense, this film feels to me more of the moment than timeless, and this year at least, I’m okay with that. Also, from a Christian perspective, there is something profoundly counter-cultural, perhaps even subversive (or, in the technical sense of the word, perverse) about Molly’s final plea. The film invokes The Crucible, but the more apt parallel may be to The Scarlet Letter. Here is a woman caught in sin who proves, perhaps, to have a far better handle on morality than does the puritanical culture that condemns her.

Other films on this list are probably aesthetically better, but if I had to pick one to rewatch right now, I would go back to Molly’s Game. Sorkin’s writing is virtuoso good, and the pleasure of hearing it delivered by Chastain and Elba, each seemingly at the peak of their craft, is considerable. Beyond stylistic preferences, it is not lost on me that many of the films on this list — Goodbye Christopher Robin, Three Billboards, The Greatest Showman, The Post — are incidentally or primarily about women trying to survive in male-dominated environments that are downright hostile towards them. In that sense, this film feels to me more of the moment than timeless, and this year at least, I’m okay with that. Also, from a Christian perspective, there is something profoundly counter-cultural, perhaps even subversive (or, in the technical sense of the word, perverse) about Molly’s final plea. The film invokes The Crucible, but the more apt parallel may be to The Scarlet Letter. Here is a woman caught in sin who proves, perhaps, to have a far better handle on morality than does the puritanical culture that condemns her.

1) First Reformed — Paul Schrader

After its successful run through the festival circuit, Paul Schrader’s film was bought last September by A24, so there’s a good chance that it may get wider distribution — and maybe an awards push — in 2018. But nothing in life is guaranteed, so when listing my favorite experiences for the year, I tend to err on the side of including festival films rather than waiting. In 2016, I esteemed The Unknown Girl and After the Storm but held off including them assuming they would garner more attention upon being commercially released. They didn’t, really. So I won’t miss any opportunity to say again what I said at Christianity Today Movies & TV: this is the Paul Schrader film I’ve been hoping most of my adult life to see. Rather than repeat what I wrote there, I’ll just add a personal observation. In 1988, I was one of those young, know-it-all Christians who called Universal to complain about The Last Temptation of Christ and even refused to buy the E.T. home video. One of the things I didn’t understand then is that movies are made by people, and people grow, develop, and change. As you grow, develop, and change, you may come to appreciate the insights and observations of those whose experiences (and hence perspectives) are different from yours. Thirty years later, I still don’t think very much of Last Temptation, but I am very grateful for Paul Schrader, appreciative of all the art he has made, and a little embarrassed by my youthful infatuation with arrogance, righteousness, and intolerance.

After its successful run through the festival circuit, Paul Schrader’s film was bought last September by A24, so there’s a good chance that it may get wider distribution — and maybe an awards push — in 2018. But nothing in life is guaranteed, so when listing my favorite experiences for the year, I tend to err on the side of including festival films rather than waiting. In 2016, I esteemed The Unknown Girl and After the Storm but held off including them assuming they would garner more attention upon being commercially released. They didn’t, really. So I won’t miss any opportunity to say again what I said at Christianity Today Movies & TV: this is the Paul Schrader film I’ve been hoping most of my adult life to see. Rather than repeat what I wrote there, I’ll just add a personal observation. In 1988, I was one of those young, know-it-all Christians who called Universal to complain about The Last Temptation of Christ and even refused to buy the E.T. home video. One of the things I didn’t understand then is that movies are made by people, and people grow, develop, and change. As you grow, develop, and change, you may come to appreciate the insights and observations of those whose experiences (and hence perspectives) are different from yours. Thirty years later, I still don’t think very much of Last Temptation, but I am very grateful for Paul Schrader, appreciative of all the art he has made, and a little embarrassed by my youthful infatuation with arrogance, righteousness, and intolerance.

One Reply to “2017 Top 10”