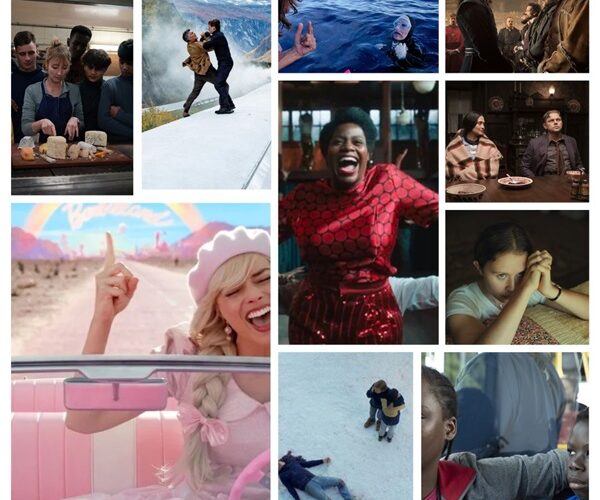

2023 Top 10

There was a lot of misery at the movies this year. Some of it was onscreen. A writer’s strike and actor’s strike didn’t exactly keep us devoid of new content, but they did seem to extend the desert between last year’s award season and the next. Causes for political, social, and environmental anxieties were probably no greater than they have ever been, but they might have seemed more prevalent when we didn’t have the escape of entertainment to distract us.

Since mine is a list of personal favorites rather than one of artistic judgments, I’ve largely avoided pronouncements from year to year about the ranking of cinematic seasons in comparison to earlier years. This year’s list felt less abundant, but perhaps that was because two local film festivals were postponed, leaving critics to try to catch up on scores of films in November and December through screening links and “For Your Consideration” screenings. First-world problem, I know, but that can lead to movie fatigue even when the slate of films isn’t as comprehensively downbeat as they appeared to be this year. Enough moaning; here’s my countdown.

10) Nyad

I find myself gravitating to negative reviews on Rotten Tomatoes these days. It’s not that criticisms are any more honest or better written, but they do more frequently prompt me to think about features of a story I might have glossed over at first glance. I largely agree with many of the criticisms of Nyad. It’s conventional. It downplays some of the more questionable aspects of Diana’s obsessive quest and the cost she is willing to demand others pay to enable her to pursue it. And I admit that after the fact, I wished for a braver film that might have examined the links, if any, between Diana’s reckless disregard for her life and the events that might have instilled that quality in her. Being tolerant of pain in the service of great accomplishments is one thing. Being driven by it to the extent that life itself becomes a chore to be endured rather than a journey to be embraced is something else. Which thing Nyad depicts is still not entirely clear to me, but I gotta love a film where people over sixty refuse to treat their aged life as insignificant. And I’m happy to see the refusal to go gentle into banal uselessness played for something other than laughs.

9) Tori and Lokita

For over a decade, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne have been some of my personal favorite filmmakers because they somehow, miraculously, manage to inject their films, grounded in the harsh modern world, with seeds of hope. For my money, the best essay on the Dardennes is Doug Cummings explanation of the significance of face-to-face communication, printed in Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema. But anyone following their filmography has probably noted that the Dadennes’s films have been a little harder in their depiction of life. The ending of Young Ahmed paralleled the ending of The Kid With a Bike in one climactic incident but deviated from it in the way that it imagined the consequences of that incident. The Unknown Girl showed how the modern world erects technical as well as emotional/spiritual barriers to face-to-face communication and how that often prevents the potentially transformative encounter with The Other from even happening.

Tori and Lokita are a pair of immigrants pretending to be brother and sister, hoping to fool Belgian officials long enough to get papers, which they assume are the passport to a normal life. In the meantime, they deliver pizzas, deliver drugs, and experience exploitation at every corner. One needn’t be a film expert to understand how vulnerable they are and all the ways their momentary equilibrium can be disrupted. But as late as the film’s closing minutes, when Lokita successfully waves at a passing motorist who stops to give her a ride, those who know the Dardennes might still be desperately hoping that they will find a way to give us an ending that is not tragic but still true. Whether they do so is open to interpretation; I’ve been argued out of misinterpretations of Dardenne films before. But I think we have in Tori and Lokita something closer to The Unknown Girl than to The Child or The Promise. We are told that even when we cannot rescue, we can still bear witness. If, increasingly, that does not feel as though it is enough, perhaps that pain in our hearts is the soul’s way of telling us something is wrong in the world and that one of our greatest dangers is that of becoming numb or resigned to the way things are.

8) Kitchen Brigade

I sometimes joke that the first film you see in any given year is, by definition, the best film of the year until you see a better one. I saw Kitchen Brigade last January, in that proverbial wasteland month where junk gets released between the end of awards qualifications and the giving out of awards. It wasn’t the best film I saw all year, but it did manage the impressive feat of staying on my annual Top 10 the whole year. I’ve linked to the full review, so there is no need to repeat what I said there. It is a modest film, admittedly formulaic. But it is executed to perfection. Like Tori and Lokita, this film deals with the harsh reality facing immigrants in today’s cultural and political landscape. But Kitchen Brigade is more aspirational and more hopeful. Does that make it more or less realistic? Maybe we live in a world where both realities can be true. If so, that means that maybe we can still try to make the part of the world we occupy more like the one we would prefer to live in. I know which one I am choosing.

7) Killers of the Flower Moon

Along with Terence Malick, Martin Scorsese is the recognized genius whose films I have the hardest time enjoying. I can, and do, appreciate them aesthetically, acknowledging their artistic accomplishments and marveling at the skill and vision required to make them. But they leave me cold in a big way. So what is it about Killers of the Flower Moon that overcame my general antipathy to the director’s work? Perhaps it is the film’s kinship to The Godfather, one of my all-time favorites. Leonardo DiCaprio kept me uncertain to the very end whether his character was in over his but trying to cling to the last piece of his soul, or whether he genuinely (and stupidly) thought that he could separate his own love and marriage from the murderous community he was embedded in. Because of DiCaprio, this is one of the few Scorsese characters who generated a modicum of pity amidst all of my revulsion.

6) The Color Purple

Honestly, I’ve never been a fan of the Spielberg film, so my appreciate for this reimagination caught me by surprise. It managed to find (or convey, if you prefer) an emotion I found sorely lacking in both the book and the more heralded film adaptation: joy. Perhaps Fantasia Burrino’s career arc as a singer better equips her to embody the gradually emboldened Celie as well as the battered and bruised Celie. Perhaps it is just the nature of music to provide more uplift. When another character says of Celie’s kindness that it is evidence of God, I was reminded, too, that the story has a spiritual core that is often missed or overlooked.

5) The Three Musketeers – Part I: D’Artagnan

Despite a Rotten Tomatoes score in the high 90s, this film seems to have come and gone without leaving much of a mark. Perhaps it was the subtitles? Given the rise of Christian Nationalism in the United States, I found something more timely in this iteration of The Three Musketeers than in other versions I’ve seen. It is nice to see a film in which characters recognize shared values despite those values being inculcated by differing religious traditions. The contrast between personal and political loyalties as a theme also landed a bit more strongly than the same material might have had this same film been made ten years ago. There’s action to spare, but it is of the type that is bounded by gravity, which makes it somehow more impressive and entertaining than the FX hijinks of costumed superheroes.

4) Anatomy of a Fall

One need not say much to justify a Palme D’Or winner on one’s list of personal favorites. Justine Triet’s writing and Sandra Hüller’s delivery are more than the some of this family melodrama’s parts. When her husband dies from a fall, Sandra suddenly finds every detail of her life under the sort of intense scrutiny that we all assume we would hold up under…until it becomes real and relentless. Structurally, we’ve seen this method of storytelling in dozens of episodes of Law & Order, but the difference here is that there is ample time to know these people, to care about their fate. Also, we won’t get the eleventh-hour evidence that sells us a certainty that rarely exists in the “real” world.

3) Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part I

The title is a mouthful, and the movie is an eyeful that’s for sure. I don’t consider myself a fan of the franchise, but this entry timed the market very well, especially by channeling the angst about AI permeating the year. By having Ethan (Tom Cruise) wanting to destroy power rather than channel it into particular hands, the film demonstrated that there was room within a pure genre flick for thoughtful ideas regarding how the world has changed. The stunts were spectacular, and I found myself appreciating the ensemble of performers in what used to just be a Tom Cruise vehicle.

2) The Starling Girl

There are a lot of films about the damaging effects of toxic religious communities. My appreciation of these is usually in proportion to the degree I think they are able to differentiate between the core, historical beliefs and teachings of the religion itself and the toxic, often abusive practices of the communities that identify themselves with that religion. In my original review, I noted that director Laurel Parmet made it a point of emphasis to not mock or condescend to all audiences in Christian communities. Those might very well include people like the titular character who have left particular communities but may not be ready to leave the faith itself. Yes, this is a virtuoso performance by Eliza Scanlen, but Jem Starling is not the only one here who is scarred by the environment she was forged in. This is a film about patriarchy that shows how it twists and mutilates the souls of men, too.

1) Barbie

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie is a little miracle of a movie. Alternately angry (America Ferrara’s speech) and understanding (“not every night has to be girl’s night”), it manages to thread an impossibly thin needle while never ceasing to be funny. Margot Robbie trusts the script enough to not ironically detach herself from the character, and Ryan Gosling manages to be adorable even when if is oblivious. Barbie is, in fact, several movies that have no business working well when rolled into one — a deconstruction and a celebration of the gender roles that have shaped and continue to shape us. By taking a both/and rather than an either/or approach, Gerwig allows us to feel the pain of confinement while also celebrating the joy of self-love.