The Queer Beauty of Vision Quest

“To be sure, male writers also ‘swerve’ from their predecessors, and they too produce literary texts whose revolutionary messages are concealed behind stylized facades.” — The Madwoman in the Attic; Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar.

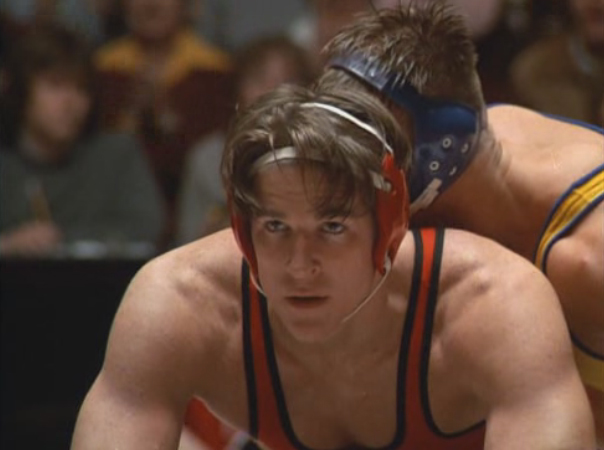

I would hardly be the first critic to suggest that its rote sports-movie structure and the presence of Linda Fiorentino as an implausibly available older woman masks Vision Quest‘s strange homoerotic subtext. On the surface, Harold Becker’s 1985 guilty pleasure about a high-school wrestler (Matthew Modine) who wants to drop two weight classes so he can take on the most feared and fearsome champion in the state has a sexual sensibility one step removed from Porky’s or Class. In retrospect, however, one of the oddest features of the film is how uninterested it is in presenting or developing Louden Swain’s thoroughly uninteresting infatuation with tough New Jersy hottie, Carla.

I would hardly be the first critic to suggest that its rote sports-movie structure and the presence of Linda Fiorentino as an implausibly available older woman masks Vision Quest‘s strange homoerotic subtext. On the surface, Harold Becker’s 1985 guilty pleasure about a high-school wrestler (Matthew Modine) who wants to drop two weight classes so he can take on the most feared and fearsome champion in the state has a sexual sensibility one step removed from Porky’s or Class. In retrospect, however, one of the oddest features of the film is how uninterested it is in presenting or developing Louden Swain’s thoroughly uninteresting infatuation with tough New Jersy hottie, Carla.

That the film goes out of its way not only to announce but to underline Louden’s heterosexual attraction to Carla could easily be construed as an example of the lad protesting too much. But I don’t think Carla is ultimately meant as a beard for either Louden or the film. He’s presented, I think, as “questioning” rather than gay. That seems ahead of the curve, because I don’t even remember that term as being part of my teen, straight lexicon in the mid 80s.

I suppose if one wanted to do a Celluloid Closet reading of Vision Quest, one might first notice the parallel ways in which Carla and Brian Shute, the male wrestler Louden longs to get on the mat with, are introduced. When we first see Carla, she is in a see-through shirt and is chastising oglers at the car dealership where Louden’s father (Ronny Cox) works. Dad gives Carla a shirt to cover up and Louden a few buck to take her to the diner while he works on her car. In other words, the sexualized male gaze is repressed. In contrast, when Louden and his friend Kuch (Michael Schoeffling) go over to Shute’s high school to watch him work out — Shute climbs stadium steps while carrying a giant log on his back — the male gaze is allowed to linger. Shute’s body, like Carla’s, is hardly contained by its clothes, but it is not treated as something that is shameful and must be covered. As Louden and Kuch stare admiringly at Shute’s physique, the rival wrestler expresses his hope that Louden will make the weight and be able to compete with him. While Carla spends most of the film rejecting Louden’s advances, Shute makes it clear that he welcomes the prospect of competing with Louden.

I suppose if one wanted to do a Celluloid Closet reading of Vision Quest, one might first notice the parallel ways in which Carla and Brian Shute, the male wrestler Louden longs to get on the mat with, are introduced. When we first see Carla, she is in a see-through shirt and is chastising oglers at the car dealership where Louden’s father (Ronny Cox) works. Dad gives Carla a shirt to cover up and Louden a few buck to take her to the diner while he works on her car. In other words, the sexualized male gaze is repressed. In contrast, when Louden and his friend Kuch (Michael Schoeffling) go over to Shute’s high school to watch him work out — Shute climbs stadium steps while carrying a giant log on his back — the male gaze is allowed to linger. Shute’s body, like Carla’s, is hardly contained by its clothes, but it is not treated as something that is shameful and must be covered. As Louden and Kuch stare admiringly at Shute’s physique, the rival wrestler expresses his hope that Louden will make the weight and be able to compete with him. While Carla spends most of the film rejecting Louden’s advances, Shute makes it clear that he welcomes the prospect of competing with Louden.

Locker rooms are easy short hand symbols for male intimacy, in part because they allow men to inhabit the nebulous emotional and sexual regions between dressed and undressed, between intimacy and normalcy. In one early scene after Carla moves into the house with Louden and his dad, the curious teen picks up and smells her panties that are in a laundry basket only to have the guest walk in on him in the midst of an embarrassing moment. By contrast, when Louden is initially deemed to be over the 168 pound weight limit, he strips completely, removing his own underwear in order to lighten himself enough to make the weight. In other words, Louden gets naked before a room full of men to show symbolically and literally how much he wants to wrestle Shute. Here again the film reverses typical straight messaging. Louden’s sexual desire for Carla — or at least the way it is expressed — is portrayed as embarrassing and humiliating, but within the context of wanting to wrestle Shute his nakedness before other men is portrayed as normal and appropriate.

Locker rooms are easy short hand symbols for male intimacy, in part because they allow men to inhabit the nebulous emotional and sexual regions between dressed and undressed, between intimacy and normalcy. In one early scene after Carla moves into the house with Louden and his dad, the curious teen picks up and smells her panties that are in a laundry basket only to have the guest walk in on him in the midst of an embarrassing moment. By contrast, when Louden is initially deemed to be over the 168 pound weight limit, he strips completely, removing his own underwear in order to lighten himself enough to make the weight. In other words, Louden gets naked before a room full of men to show symbolically and literally how much he wants to wrestle Shute. Here again the film reverses typical straight messaging. Louden’s sexual desire for Carla — or at least the way it is expressed — is portrayed as embarrassing and humiliating, but within the context of wanting to wrestle Shute his nakedness before other men is portrayed as normal and appropriate.

None of this necessarily means Louden is gay. He’s not. He’s straight. At least he thinks he’s straight. He (eventually) has sex with Carla. And in an early scene, while working at hotel as a bellboy, he rejects an overture from an apparently gay man who is practicing Tai Chi. Louden writes an editorial for the school newspaper on the clitoris, claiming he wants to be a gynecologist so that he might look into women and better understand the power they have over him. All of these are overt signals of his heterosexuality. But other than Carla, the power women have over him seems more stated than illustrated. Mom is absent, and Louden has no apparent interest in girls his own age, like Margie (Daphne Zuniga). As an aside, when Margie runs Louden’s essay on the clitoris, the school gives them both detention, yet another example where intimations of heterosexuality are responded to in a shaming way.

None of this necessarily means Louden is gay. He’s not. He’s straight. At least he thinks he’s straight. He (eventually) has sex with Carla. And in an early scene, while working at hotel as a bellboy, he rejects an overture from an apparently gay man who is practicing Tai Chi. Louden writes an editorial for the school newspaper on the clitoris, claiming he wants to be a gynecologist so that he might look into women and better understand the power they have over him. All of these are overt signals of his heterosexuality. But other than Carla, the power women have over him seems more stated than illustrated. Mom is absent, and Louden has no apparent interest in girls his own age, like Margie (Daphne Zuniga). As an aside, when Margie runs Louden’s essay on the clitoris, the school gives them both detention, yet another example where intimations of heterosexuality are responded to in a shaming way.

I wouldn’t pick a fight with anyone who wants to claim Louden is gay and that this pattern of overt attempts at public heterosexuality is a common trope for closeted or troubled homosexuals. Emotionally, though, Louden doesn’t appear to fit this pattern. He does not seem to be particularly troubled with expressing himself emotionally, nor does he appear to be particularly scared by his sexual feelings. He tells Kuch that he was freaked out by the hotel guest grabbing his “wad,” but one of the remarkable things about this scene is the relative calm with which a straight high-school male rebuffs an overt homosexual overture. In other films we might expect Louden to express contempt or disgust at this prospect — or self-doubt about whether he was putting out scent — but here Louden simply leaves the hotel room, telling the guest to deposit the room service tray in the hall when he is done.

I wouldn’t pick a fight with anyone who wants to claim Louden is gay and that this pattern of overt attempts at public heterosexuality is a common trope for closeted or troubled homosexuals. Emotionally, though, Louden doesn’t appear to fit this pattern. He does not seem to be particularly troubled with expressing himself emotionally, nor does he appear to be particularly scared by his sexual feelings. He tells Kuch that he was freaked out by the hotel guest grabbing his “wad,” but one of the remarkable things about this scene is the relative calm with which a straight high-school male rebuffs an overt homosexual overture. In other films we might expect Louden to express contempt or disgust at this prospect — or self-doubt about whether he was putting out scent — but here Louden simply leaves the hotel room, telling the guest to deposit the room service tray in the hall when he is done.

One of Louden’s most endearing features is curiosity, and his curiosity about Tai Chi is perhaps misunderstood as sexual curiosity. But Louden is sexually curios, too. And that’s different from being sexually avaricious. In the film’s opening monologue, Louden states that he is eighteen and hasn’t done “anything.” His name, “Swain,” can mean “young lover” but it can also mean “country youth” (i.e. inexperienced). In perhaps the film’s most pointed and telling exchange, he tells Carla he is a virgin and asks if that makes him weird or strange. She says it simply makes him who he is, which is something that “by the way” she thinks is “pretty terrific.” Carla eschews sexual orientation categories, suggesting that each person’s sexuality is unique. In doing so, she gives him permission to think of himself as an individual and to not have to worry about which box to check or which category to place himself in.

Louden’s concluding voice-over is similarly more effective at framing the film as a sexual coming-of-age story than a sports story. He says:

But all I ever settled for is that we’re born to live and then to die, and… we got to do it alone, each in his own way. And I guess that’s why we got to love those people who deserve it like there’s no tomorrow. ‘Cause when you get right down to it – there isn’t.

Certainly the “live like there is no tomorrow” line foreshadows the “carpe diem” message of Dead Poet’s Society (1989) and acts as the exclamation point for the sports story. In Nike terms, Louden just does it. But, really, what does all this talk of dying alone and loving people who deserve it have to do with Louden’s vision quest?

Perhaps the wrestler’s dream of conquest is simply the universal human dream of excelling. When Louden’s co-worker, Elmo, explains why he is taking a day off work to see Louden wrestle Shute, he cites Pele’s famous bicycle kick as a “glorious” example of an individual uniting disparate people and cultures and allowing them to momentarily feel and rejoice in their shared humanity.

Perhaps the wrestler’s dream of conquest is simply the universal human dream of excelling. When Louden’s co-worker, Elmo, explains why he is taking a day off work to see Louden wrestle Shute, he cites Pele’s famous bicycle kick as a “glorious” example of an individual uniting disparate people and cultures and allowing them to momentarily feel and rejoice in their shared humanity.

Sports can do that, absolutely. But I think it is telling — and beautiful — that Louden himself, having proven that humans can surmount seemingly impossible obstacles when they live fearlessly and pursue their dreams purposefully, underlines that the message learned by his quest is to love the people you love like there is no tomorrow.

All of us, gay or straight, have trouble loving fearlessly. Expressing our true selves, even to ourselves or to God, much less to the people we desire, can be terrifying. The queer beauty of Vision Quest is that it allows us, gay or straight, to identify the best, bravest versions of ourselves, with a young man who chooses to pursue his heart’s deepest longing rather than that which he has been told is more socially acceptable. Ultimately, perhaps the sports story isn’t a cover for the sexual bildungsroman so much as a metaphor for it. Certainly the quest to achieve the seemingly impossible will have certain resonances for gay viewers, just as it will resonate in other ways for straight viewers. Narrative is more interesting than allegory precisely because it can be appropriated rather than merely decoded.

Would a sequel set ten years later reveal that Louden came to realize he is gay? (Or bisexual?) I guess the best possible answer to that question is, “who cares?” I certainly don’t.

Notice how after the incident where the hotel guest grabs Louden’s wad, the next time we see Louden leave work, he’s got a brand new pair of red wrestling shoes slung over his shoulders… exactly what the wad grabber, a sports gear salesman, promised he could give Louden.

You’re right Jay Dog

Jay Dog it’s the most overtly homosexual reference in the whole movie, and missed by the author of this piece. How or more accurately, what did Louden have to do to get those shoes?