Janis: Little Girl Blue (Berg, 2015)

I tend to think of Amy Berg as an underrated director, which is an admittedly odd statement to make about a woman whose most recent documentary, Janis: Little Girl Blue (★★★) is over 90% “fresh” at Rotten Tomatoes.

Berg, though, tends to pick topics that people are passionate–and passionately informed–about: the West Memphis Three, a pedophile priest, child exploitation in Hollywood, Janis Joplin. If you know Janis better than I know Janis, you probably think that I don’t know Janis at all.

Guilty as charged. Beyond singing “Me and Bobby McGee” on Rock Band and knowing the singer overdosed at a relatively young age, I am mostly ignorant of her biography and body of work. Why is she (musically) important? What were her influences and who influenced her? I’m still not sure I could answer those questions with much erudition. That’s okay, though. Since when is a single documentary supposed to transform a relatively uninformed viewer from a curious consumer into an academic expert?

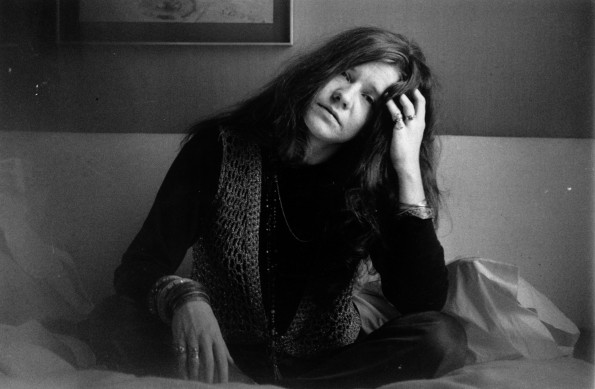

What the film does do well is convey an emotional portrait of the troubled singer. Berg juxtaposes generous amounts of concert and performance footage with excerpts of Joplin’s letters read (performed?) by Cat Power. Yes, the depressed artist searching for love in all the wrong places is itself a bit of a stereotype, but here’s what always fascinates me about documentaries (and biopics) about geniuses: did they know? Or were they so busy convincing themselves and the world, so busy making art or computers or music, that they never caught a glimpse of their own incandescent brilliance?

What the film does do well is convey an emotional portrait of the troubled singer. Berg juxtaposes generous amounts of concert and performance footage with excerpts of Joplin’s letters read (performed?) by Cat Power. Yes, the depressed artist searching for love in all the wrong places is itself a bit of a stereotype, but here’s what always fascinates me about documentaries (and biopics) about geniuses: did they know? Or were they so busy convincing themselves and the world, so busy making art or computers or music, that they never caught a glimpse of their own incandescent brilliance?

Joplin’s letters, which interest me as much if not more than the performance footage, reveal a woman who seemed capable of finding some measure of happiness in her own talent, even if it didn’t always emerge and develop in ways she wanted. (When does it ever?)

I am sympathetic to Alan Scherstuhl’s review in The Village Voice: “Berg’s assemblage of home movies, performance footage, and vintage interviews is marvelous, but there’s not an idea in the movie’s head except she suffered, she sang, maybe heroin kept the hurt away.”

Okay, fine, I’ll concede that maybe the portrait painted of Joplin is neither particularly new (I wouldn’t know) nor particularly complex (maybe the fact that she suffered, sang, and took heroin is the film’s idea). But the construction of that sentence is also telling. Why is the “marvelous” assemblage of “home movies, performance footage, and vintage interviews” dismissed so summarily? For those, like me, who have never seen the footage before, who are being introduced to Joplin’s biography rather than picking over it, the film serves perfectly well.