Feel “Better” Movies — What to Watch When the News is Bleak

The news has not been good this week.

I’d contextualize that statement, but I realized that in a month or two or six, today’s senseless horrors will probably have given way to others and that such a statement may be equally apt, even if it has a different antecedent.

“If it bleeds, it leads,” is a cynical but seemingly indisputable description of how media (mainstream and social) gets our attention. The psychological effects of being constantly asked to focus on the world’s problems is paradoxically well documented and perhaps only peripherally understood. (I recommend The Culture of Fear for a better articulation of those costs than I can give here.)

I wanted to write a post about films I turn to when I just can’t take the bad news any more, when I’m fed up with human nature, or when my capacity to respond productively to the “real” world is exahausted. Here’s the thing, though: I dislike the term “feel good” as a label for grand art. For me, it connotes something chippy, chirpy, maybe even facile. The films that help me most in such times are seldom cheerful, never superficial. They do, however, remind me that while we as a race are capable of great evil, a catalog of our worst atrocities is not a sufficient description of who we are.

Here are five films that make me feel better when I’m feeling bad about…everything else.

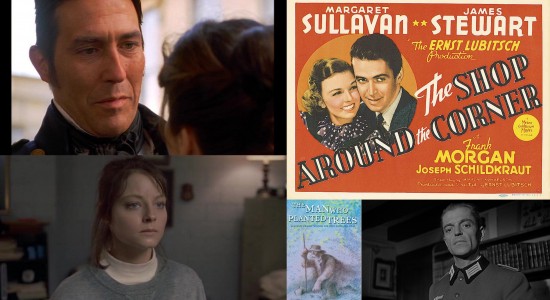

5) The Silence of the Lambs

The most counter-intuitive film on my list, Jonathan Demme’s adaptation of Thomas Harris’s violent-crime novel is about an admittedly dark subject: serial murder. It’s also spawned a host of imitators that have cluttered our movie screens and television sets with violent images, predominantly of horrors perpetrated against women. And yet…Clarice Starling and Jack Crawford never fail to inspire me in the way they pursue saving victims of monsters no matter the personal cost. I also tend to think–and in this I realize I am both politically incorrect and in the minority in this view–that the monster, Buffalo Bill, engenders just the tiniest sliver of compassion. Not in a politicized “they made him” kinda way. Not really in any way that suggests there is any viable option other than putting him down. But his actions seem to come from a place of pain, and self-loathing, and confusion that even he does not understand. In the years that followed, all of us (including Harris himself I think) fell in love with the character of Hannibal Lecter, forgetting Crawford’s admonition to not let him in your head. Finally there is Clarice who chooses to identify with the victim–who chooses a share of suffering for a chance to alleviate that of others. That her suffering is psychological rather than physical makes her sacrifice no less moving. Rare are the heroes who win by having the strength to be vulnerable rather than by stifling the best parts of themselves.

The most counter-intuitive film on my list, Jonathan Demme’s adaptation of Thomas Harris’s violent-crime novel is about an admittedly dark subject: serial murder. It’s also spawned a host of imitators that have cluttered our movie screens and television sets with violent images, predominantly of horrors perpetrated against women. And yet…Clarice Starling and Jack Crawford never fail to inspire me in the way they pursue saving victims of monsters no matter the personal cost. I also tend to think–and in this I realize I am both politically incorrect and in the minority in this view–that the monster, Buffalo Bill, engenders just the tiniest sliver of compassion. Not in a politicized “they made him” kinda way. Not really in any way that suggests there is any viable option other than putting him down. But his actions seem to come from a place of pain, and self-loathing, and confusion that even he does not understand. In the years that followed, all of us (including Harris himself I think) fell in love with the character of Hannibal Lecter, forgetting Crawford’s admonition to not let him in your head. Finally there is Clarice who chooses to identify with the victim–who chooses a share of suffering for a chance to alleviate that of others. That her suffering is psychological rather than physical makes her sacrifice no less moving. Rare are the heroes who win by having the strength to be vulnerable rather than by stifling the best parts of themselves.

4) The Shop Around the Corner

I introduced my essay on Tom Tykwer in Volume II of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema by quoting the German director trying to define the famous “Lubitsch touch.” He says: “To me, the most distinctive aspect of the Lubitsch touch is always the principle of hope. After watching his films, I felt optimistic. As if I could go through life and smile about the insanity that rains down on us. That’s why the films have a medicinal effect” (212) . In what is arguably Lubitsch’s best known film, the hope is that two people who love each other and are well suited for one another will break out of their painful habits long enough to receive the happiness the universe would just assume give them. The backdrop against which the domestic drama plays is admittedly smaller than that of To Be or Not to Be, but there are strands of larger sociological conflicts weaved into the personal story. The Shop Around the Corner ends on Christmas Eve, a setting, perhaps, that subtly reminds us that most of the good things in life are gifts we’ve been given rather than wages we have earned. Give every man what he deserves, Hamlet once said, and none of us would escape whipping. Or to paraphrase C. S. Lewis, the true generosity of God is that He so often gives us what we really want rather than what we have demanded or asked for.

I introduced my essay on Tom Tykwer in Volume II of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema by quoting the German director trying to define the famous “Lubitsch touch.” He says: “To me, the most distinctive aspect of the Lubitsch touch is always the principle of hope. After watching his films, I felt optimistic. As if I could go through life and smile about the insanity that rains down on us. That’s why the films have a medicinal effect” (212) . In what is arguably Lubitsch’s best known film, the hope is that two people who love each other and are well suited for one another will break out of their painful habits long enough to receive the happiness the universe would just assume give them. The backdrop against which the domestic drama plays is admittedly smaller than that of To Be or Not to Be, but there are strands of larger sociological conflicts weaved into the personal story. The Shop Around the Corner ends on Christmas Eve, a setting, perhaps, that subtly reminds us that most of the good things in life are gifts we’ve been given rather than wages we have earned. Give every man what he deserves, Hamlet once said, and none of us would escape whipping. Or to paraphrase C. S. Lewis, the true generosity of God is that He so often gives us what we really want rather than what we have demanded or asked for.

3) The Silence of the Sea

Of the making of World War II films there is no end. Because Nazis are such an easy metaphor for absolute evil, every generation finds in them a type of its own figures of depravity. The Silence of the Sea is about resistance. A Frenchman and his niece, forced to house a German officer, capitulate, but they refuse to speak. The psychological effects, both on the German and on the protesters, is profound. It is customary to describe the powerless as voiceless, and by making that metaphor literal the film invites us to meditate on how much we use words as weapons and more words as armor. Like The Silence of the Lambs, this film has a sadness about it that I ultimately find more palliative than the exuberance of more triumphant heroes. Plus the scope of evil often makes us feel as though there is nothing we can do; films about normal people responding to impossible demands are always more gripping than ones about alien superheroes or costumed mutants. Here as well we have an antagonist who, while not sympathetic enough to change our allegiances, reminds us that the deepest divides sometimes separate people on both sides who haven’t yet stopped questioning. If a Frenchman could admit this much about a German in 1949, is it really impossible for us to believe today that there might yet be those we fight whose consciences have not yet been extinguished?

Of the making of World War II films there is no end. Because Nazis are such an easy metaphor for absolute evil, every generation finds in them a type of its own figures of depravity. The Silence of the Sea is about resistance. A Frenchman and his niece, forced to house a German officer, capitulate, but they refuse to speak. The psychological effects, both on the German and on the protesters, is profound. It is customary to describe the powerless as voiceless, and by making that metaphor literal the film invites us to meditate on how much we use words as weapons and more words as armor. Like The Silence of the Lambs, this film has a sadness about it that I ultimately find more palliative than the exuberance of more triumphant heroes. Plus the scope of evil often makes us feel as though there is nothing we can do; films about normal people responding to impossible demands are always more gripping than ones about alien superheroes or costumed mutants. Here as well we have an antagonist who, while not sympathetic enough to change our allegiances, reminds us that the deepest divides sometimes separate people on both sides who haven’t yet stopped questioning. If a Frenchman could admit this much about a German in 1949, is it really impossible for us to believe today that there might yet be those we fight whose consciences have not yet been extinguished?

2) Persuasion

Who doesn’t love a good love story? And nobody does a love story better than Jane Austen.

Who doesn’t love a good love story? And nobody does a love story better than Jane Austen.

Persuasion is not my favorite Austen novel; that would be Emma. Neither is the Root-Hinds film my favorite adaptation; that would be Pride and Prejudice. What Persuasion does have over those other works, though, is a pair of themes that act as a balm to the heartbroken soul. It is a film about second chances. Sometimes the things we do seem right or necessary at the time but have blow back that makes us wish we could choose differently. Second, the film is about hope. A special kind of hope, actually. The hope strong enough that its very memory sustains us after it has been absent so long that we think it is dead. “It is such a happiness when good people get together,” Austen writes in another novel. “And they always do.” Austen’s world is one in which good things invariably happen for good people. Maybe it’s naive to believe that such is always the moral nature of our own world, but maybe it’s not. Maybe that’s the underlying moral fabric of the universe and we only catch glimpses of it occasionally because we see through a glass, darkly.

1) The Man Who Planted Trees

Canadian animator Frédéric Back created a short film that is every cliche in the superlative dictionary: a timeless masterpiece, a labor of love, and an immersive experience. Based on Jean Giono’s book of the same title, this short film is a consummate example of the marriage of form and style. The story is about a man who salvages a ruined ecosystem through meticulous labor. The film, like the shepherd’s landscape, begins somewhat bare. The drawings are minimal, with little detail. Gradually, as Eleazar Bouffier greens the landscape, the settings are rendered more vibrantly, but the transformation is so gradual that it is often imperceptible. There are many films and stories about heroes who make one big sacrifice or one grand gesture. Because we are impatient in our souls, we look for those grand gestures and so often look past those whose years of diligent, faithful service bear fruit in the tiniest increments.

Canadian animator Frédéric Back created a short film that is every cliche in the superlative dictionary: a timeless masterpiece, a labor of love, and an immersive experience. Based on Jean Giono’s book of the same title, this short film is a consummate example of the marriage of form and style. The story is about a man who salvages a ruined ecosystem through meticulous labor. The film, like the shepherd’s landscape, begins somewhat bare. The drawings are minimal, with little detail. Gradually, as Eleazar Bouffier greens the landscape, the settings are rendered more vibrantly, but the transformation is so gradual that it is often imperceptible. There are many films and stories about heroes who make one big sacrifice or one grand gesture. Because we are impatient in our souls, we look for those grand gestures and so often look past those whose years of diligent, faithful service bear fruit in the tiniest increments.

One of the most encouraging themes of The Man Who Planted Trees is that one person–a shepherd, a beekeeper, a storyteller, an animator–can make a difference. The power of compound interest is as latent in our labor as it is with our money. It is true that sometimes our work is unappreciated and unrecognized. It is true that sometimes the stupidity of war, the blindness of politicians, and the brokenness of our neighbors, hinders and thwarts us in our attempts to promote the public good. But it is also true–and we should never forget–that while the span of a man’s life is as brief as the wind, the good he can do in that span is nothing short of miraculous.