2015 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, Day 3: Outsider Art, Afghan Archeology, African Democracy, and the Black Panthers

I started my final day at Full Frame with a pair of short documentaries. The first one, Abandoned Goods, covers a lot of ground in its lean 36 minutes. In telling the story behind the Adamson Collection, several thousand artworks completed by institutionalized psychiatric patients in England, this film also contains a miniaturized history of mental health care across the Twentieth Century.

All of the drawings, paintings, and sculptures in the collection were created by residents of the Netherne Hospital in Southeastern England. When this facility opened in the early 1900’s, its lovely brick buildings, complete with an indoor swimming pool, epitomized the move towards the humane treatment of long-term sufferers of mental illness both in America and Europe.

Alas, the number of patients outstripped resources, and eventually they were crammed together into spaces designed for far fewer individuals. As the century progressed, the residents were subjected to faddish, ineffectual treatments such as lobotomies and other psychosurgeries. By the end of the century, deinstitutionalization was in full swing, and the doors finally shut on Netherne Hospital for good in 1993.

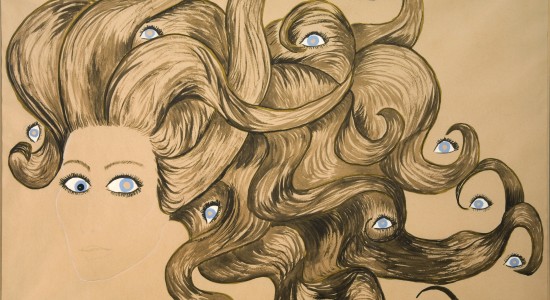

The co-directors and writers of Abandoned Goods, Pia Borg and Edward Lawrenson, have structured their film in a fascinating manner. Closeups of selected artworks alternate with photos and video footage of patients and doctors across the years, all backed by an eerie solo organ score. The art itself is a curious mishmash of childlike sketches, primitive pastorals that resemble work by Grandma Moses, and highly sophisticated, Bosch-like hells.

To the directors’ credit, they avoid overt editorializing as they chronicle the migration of this outsider art from neglected storeroom to Parisian gallery. I don’t know if Borg and Lawrenson intended this, but it’s definitely troubling to see this work travel from clinical scrutiny in search of psychopathology, to the aesthetic gaze of art criticism. Questions of patient confidentiality and compensation for artwork completed in dire, deprived circumstances also went unanswered in this uneasy film.

While Abandoned Goods circles around art lost then recovered, the second short tells us of history found and now in danger of obliteration. Saving Mes Aynak is the somber tale of a great archaeological find outside of Kabul, threatened by Chinese mining interests and the Taliban.

Mes Aynak was a key stop along the ancient Silk Road, the trade route that connected the Mediterranean with China and India. However, its settlement dates back as far as 3000 BCE, with evidence of early copper mining and numerous Buddhist monasteries.

Unfortunately, we may never discover all of the history and beauty currently buried at this site. A Chinese government-run company wants to convert this Pompeii-sized locale into an open copper mine. This is bad news for the villagers in Mes Aynak’s environs, too, given the abysmal track record of such businesses for polluting the land and poisoning the water. And contented Afghan politicians, strongly suspected to be recipients of generous bribes, can’t be counted on to intervene.

Swimming against this overwhelming tide of short-sighted cupidity is the hero of Saving Mes Aynak. Lead Afghan archeologist Qadir Temori not only contends with the ticking countdown to this site’s closure, but faces Taliban death threats, unreliable paychecks, and condescending European colleagues.

Director Brent E. Huffman deserves a medal of his own for braving the Taliban to create this film. As such, I wish I could give his completed product an unqualified thumbs up. Unfortunately, Saving Mes Aynak needed tighter editing of some superfluous filler, as well as fuller explanations in other places. We’re shown many stunning examples of the discoveries made here so far: statues of Bodhisattvas, gold coins, a copper-stained skeleton. However, more details about the significance of these finds and the history of the dwellers of Mes Aynak would’ve turned these appetizers into a filling meal.

(I’m frustrated, too, because Huffman offered several tasty facts during his Q&A that would’ve only enhanced his film. For instance, the director was persona non grata at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, very likely because the Americans want to wash their hands of the mess they’re leaving behind, and for fear of upsetting the Chinese government. Curiously, too, the Dalai Lama has refused to condemn the pending destruction of Mes Aynak, despite its religious significance.)

The themes of the third film of the day, Incorruptible, are just as boldly humanistic, but stronger in their execution. Remarkably, this was also the second new documentary by director Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi screened at Full Frame. (The first one, the gripping and delightful Meru, was co-directed with her mountain-climbing husband Jimmy Chin.)

With remarkable access to all of the key players in the story, Incorruptible documents the 2012 presidential election in Senegal. This was a year the wheels threatened to fly off the democracy of this West African nation. The current president, Abdoulaye Wade, was flagrantly violating his country’s constitution in running for a third term.

In his dozen years in office, Wade had plundered hundreds of millions from his country’s treasury, used the police as his personal security force, and shamelessly schemes for his son to follow him in office. In the meantime, unsurprisingly, Senegal wallows in poverty, malnutrition, and high unemployment rates.

Squaring off against Wade are multiple candidates, including a former Wade lackey named Macky Sall (who professes to have seen the error of his former ways) and, astonishingly, the musical legend Youssou N’Dour.

In the streets, a youth movement called Y’en a Marre (Enough is Enough) has coalesced under the leadership of journalists and socially conscious rappers. They refuse to back a single candidate, but cry out for reform at their rallies. The street protests threaten to become fully anarchic, with burning barricades and rock throwing. Courageously, director Vasarhelyi and her camera crew capture all of this, even as the police respond with tear gas, bullets, and water cannons.

There’s a curious religious element to these political machinations as well. President Wade pays off a Sufi Muslim leader to throw his considerable influence behind his incumbency. If progressive Americans shudder at the Election Day influence of the religious right, James Dobson and Billy Graham are a belch in a hurricane compared to the apparent power of Cheikh Bethio over his sheep, who bleat in unison that they’ll do whatever the Cheikh orders them to do.

By way of contrast, Y’en a Marre partisans are children of the Enlightenment, proclaiming that they will not yield to the temptation of the herd instinct. They confidently commit to obey reason, rather than sway to the emotional seduction of politicians and religious persuaders.

Watching Incorruptible, I longed for more biography, history, and context for the efforts of Y’en a Marre, but props are due Vasarhelyi for shaping a taut chronicle about a neglected corner of the world, prompting concern for fellow humans who normally garner little media coverage.

The last film of the evening – The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution – is the latest by esteemed director Stanley Nelson. Having made a name for himself with other documentaries about key aspects of black history, as well as accounts of Jonestown and Wounded Knee, I suspect this new work will become the definitive video account of the Black Panther Party.

Nelson succeeds in placing us at the founding of the Black Panthers in 1966 in Oakland, originally as a self-defense organization, later becoming concerned with social justice both far-ranging (employment for all) and short-term (feeding hungry schoolkids). He takes us through the organization’s confrontations with L.A. and Chicago police, stoked by J. Edgar Hoover’s loathing and mistrust, and ultimately to the Black Panthers’ dissolution.

All of this is told expertly, through a proficient synthesis of historical footage, news broadcasts of the era, and present-day interviews with key figures inside and outside of the movement. Nonetheless, I felt as if the storytelling was a bit detached, while the portion telling of the group’s demise dragged on too long. I was left fatigued rather than galvanized by the film’s end, admiring rather than loving Nelson’s work.

Abandoned Goods: 4 out of 5 stars

Saving Mes Aynak: 3.5 out of 5 stars

Incorruptible: 4 out of 5 stars

The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution: 3.5 out of 5 stars