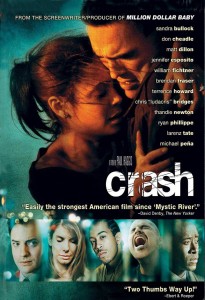

Crash (Haggis, 2005) — 10 Years Later

At some point in between the wee hours of March 5, 2006 (or March 6 if you were in the Eastern time zone), when Crash was anointed the best narrative film of the previous year and today…something happened.

What that “something” was is open to debate. Either the film had its flaws exposed or its audience had a drastic change of heart. Either way, Paul Haggis’s directorial debut is now seen as the poster child for bad Academy Awards choices. The Online Film Critics Society ranked it eighty-fifth out of eighty-six choices in its “Best of the Best Picture” poll in 2013. (Full disclosure: I am a member and voted in that poll). The film did only marginally better at Indiewire, coming in at eighty-one in that organization’s poll. (I’m a member there too, but I didn’t vote in that particular poll.) I get that critics aren’t Academy voters, but it does seem strange that a film can undergo that much a critical reassessment in the span of a decade.

Has it? Or was 2005 simply a bad year for nominated films? I set out to find out by reviewing Haggis’s film for the first time since its theatrical release.

What I Said Then

(from a review at Viewpoint, a precursor to this blog)

Crash is one of those films where occasional acts of transcendent kindness are supposed to be all the more poignant because of the pervasive hopelessness that surrounds the characters who make them. Those moments don’t lead to any epiphanies, though, and after awhile the relentless nature of the racism that pervades the film appeared to send the message that no epiphanies or progress were even possible. As a result of that view–more pessimism than cynicism–the small moments of faith and kindness didn’t really serve as a life preserver in a sea of hate, they simply got washed away in the tide with everything else.

At 113 minutes, Crash is both plodding and packed. It has a television show’s density; there is no room for development or rhythm, only repetition. Each scene has to be filled with significance, and, as one climactic resolution follows another, each must add another exclamation point to the themes that have already been bolded, underlined and practically shouted at us: racism is bad, people are an unpredictable mix of good and evil, we are more intimately connected to those we hate than we think and further separated from those we love than we admit.

This film is the first directed by Paul Haggis (he has directed for television previously) whose writing credits include–no, this is not a typo–Million Dollar Baby, L.A. Law, and The Love Boat, among others. One thread that ties these works together is the use of interlacing story lines. Million Dollar Baby was a compilation of several short stories, while Law, The Love Boat, and other television works often used the formula of intersecting story lines to reinforce the same theme. (Of course, to be fair, so did Hamlet and King Lear, so it’s not as though there is anything inherently wrong with that formula.) The down-side, for me anyway, of this structure is that it can reduce all the stories to a similar, shallow depth. The cast is excellent at fleshing out what are essentially not three dimensional characters but rather plot pawns, yet even the formidable talents of Don Cheadle, Thandie Newton, and Brendan Fraser can’t quite make them people. These characters emote–they don’t live.Another similarity to Million Dollar Baby is the tone of weary resignation. In fact, I thought of Million Dollar Baby and the choices made by the two protagonists a lot as I was watching the lives of various characters unravel at the end of Crash. If it is okay on an individual level to simply give up, to lose all hope that transformation is possible or that life is worth living, is it not equally possible to believe that the same may be true of a culture? If so, aren’t attempts to overcome adversity (from without and within) really just vain pursuits after the ecclesiastical wind

Crash begins with a thesis statement monologue about how crashing into one another has become the only way of achieving human contact. This speech is supposed to explain, at least partially, many of the characters’ proactive animosity. For me, however, Sandra Bullock’s character (Jean) delivers the truer thesis of the film, ironically, when she is on the phone to another character that is not present. “I wake up angry every day,” Jean says, “and I don’t know why.” Earlier this summer The Interpreter tried to pawn off vengeance as “lazy grief” — a cliché that didn’t quite work for me. Knowingly or not, this scene in Crash presents a fairly credible explanation for racism–it is lazy anger, lazy disappointment, or lazy frustration. It is the path of least resistance when we feel pain, disappointment, or fear. We could examine our feelings and try to understand how our situation is the product of myriad social, political, economic and social conditions, but how much easier to find a scapegoat–whether it be the dark skinned man that terrorizes us or the light skinned one that oppresses us?The film ends with a group of refugees being welcomed to America and the conclusion is supposed to be (I think) one of those moments that makes us appreciative of all that we take for granted–you know, the worst form of government except for all the others. America may be hopelessly mired in hatred, despair, and violence, but everyone wants to come here, so there must be something good that we’ve lost sight of, right?

Right?

What I Say Now

I gave Crash a “B-” ten years ago, and a second look didn’t make me want to alter that assessment.

If, perhaps, the structural device of interweaving story lines looks and feels a little more superficial now than it did in 2005, I attribute that at least in part to poorer imitators the film spawned . Not that it was the first film to offer such a structure, but it is such a cultural reference point in that regard. (I was at a set visit earlier this year and heard more than one film participant name-drop the title as a short-hand for describing the new film’s structure.)

I think it was Gene Siskel and not Roger Ebert who observed that films with alternate story lines are only as interesting as each individual story line would be on its own. The same might be said of films with multiple story lines. It’s not as though Haggis’s script doesn’t have a talent for drawing me into individual scenes…the traffic stop in which Matt Dillon’s racist cop fondles Thandie Newton’s character goes from zero to sixty in a heartbeat. But I agree with my earlier comment about repetition. We get one (or two?) more scenes between Newton and Terence Howard (as her husband) before we’re off to the accident where Dillon pulls an hysterical Newton from the burning wreckage. The general lack of development between set up and payoff means the latter lacks the emotional power it should have were it the focal point of its own movie. (The same could be said of payoff scene between Michael Peña’s locksmith and the daughter whose fears he soothes by giving her an imaginary, invisible cape to protect her.)

Maybe one place that I softened slightly on the film had to do with its relentless portrayal of negative timing. Characters always show just the worst side of themselves at just the wrong time–that is, at just the time that will have maximum dramatic flashiness and maximum negative impact on others. Earlier this summer, I made the same comment about Boyhood. Having spent more time on the Internet in the last decade, I’m willing to cut the film some slack here. Whereas I thought this was about structural irony and the ripple effect of hatred, I’m willing to at least entertain that notion that a broad percentage of our society lives in a state of simmering anger, needing less and less to tip them over the edge into full-scale meltdown. Even so, some of Crash‘s scenes, such as the one in which Dillon’s character tries to shame an African-American clerk with snide insinuations that she is an affirmative-action hire, play more like stand-alone audition scenes than fully integrated snapshots of a consistent character. Only in the Pulp Fictionesque banter of two carjackers and in one day-after fight between Newton’s and Howard’s characters do we see characters get any push back for their rants.

Maybe one place that I softened slightly on the film had to do with its relentless portrayal of negative timing. Characters always show just the worst side of themselves at just the wrong time–that is, at just the time that will have maximum dramatic flashiness and maximum negative impact on others. Earlier this summer, I made the same comment about Boyhood. Having spent more time on the Internet in the last decade, I’m willing to cut the film some slack here. Whereas I thought this was about structural irony and the ripple effect of hatred, I’m willing to at least entertain that notion that a broad percentage of our society lives in a state of simmering anger, needing less and less to tip them over the edge into full-scale meltdown. Even so, some of Crash‘s scenes, such as the one in which Dillon’s character tries to shame an African-American clerk with snide insinuations that she is an affirmative-action hire, play more like stand-alone audition scenes than fully integrated snapshots of a consistent character. Only in the Pulp Fictionesque banter of two carjackers and in one day-after fight between Newton’s and Howard’s characters do we see characters get any push back for their rants.

The Verdict

Is it possible that Crash was just everyone’s second choice? Perhaps Brokeback Mountain and Caopte were perceived as too gay, Good Night and Good Luck as too Clooney, and Munich as too Spielberg. Or perhaps all those films were just fine but appealed to different demographics, splitting the votes of people who didn’t care for Crash. Maybe the film rode its associations to Million Dollar Baby. (Despite that film’s success, Haggis missed out on a screenplay Oscar when Alexander Payne took the prize for Sideways.)

Whatever the reasons for the backlash, it does feel more like backlash than reassessment. Crash isn’t a bad movie, and perhaps if it hadn’t been trumpeted as loudly as it was, we would be more willing to concede its modest virtues. Dillon has never been better, and Sandra Bullock, still five years away from her own Oscar, begins to break away from the light comedy she had been typecast in and towards the more serious roles that she is, quite frankly better at. Haggis the director fell back to earth pretty quickly: The Valley of Elah and Third Person were not met with the same enthusiasm as Crash, but perhaps the backlash had already begun? He did go on to write the script for Casino Royale, so I might argue that he was more influential than anyone except Daniel Craig in revitalizing the Jame Bond character.

I guess what I’m saying is that if one wants to to argue that time has revealed Crash as a fraud, there’s ammunition for that argument to be found, but I would understand the vitriol better if I thought it was a legitimately bad film or if it had caused some masterpiece to get slighted. I had Capote and Munich rated higher, and one could argue that the arcs of Hoffman’s and Miller’s careers have improved the former’s reputation. Those films are not without their flaws either, though, and while my respect for Crash is begrudging, it is nevertheless sincere.

What say you, readers? Do you think Crash gets a bad rap–or does the mere mention of the title set your teeth on edge?

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=durNwe9pL0E[/youtube]

I was actually thinking about Crash the other day as I was browsing my movie collection and noticed its presence. I never thought it was a *bad* film, only a semi-decent film that had a lot of emotional fervor behind it in 2005, which quickly waned (akin to Slumdog Millionaire). It is interesting that the themes of Crash–racism, latent anger, the interconnectedness of all things–are still prevalent in both present-day films and culture, but are much more interesting. There are other 2005 films beyond the Best Picture nominees I find compelled to revisit 10 years layer, including The New World, A History of Violence, Pride and Prejudice, Batman Begins, The Proposition, and Cache.