The Queen of Versailles (Greenfield, 2012)

Not just one of the best documentaries at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, Lauren Greenfield’s The Queen of Versailles deserves to be in the conversation as one of the best films of 2012.

What begins as a film about treasures—the largest home in America under one roof and the people and objects that occupy it—becomes a film to treasure, a complex, nuanced, funny, scary and oddly sympathetic look at what we value as a culture and the stories we tell ourselves to justify the ways we choose to live.

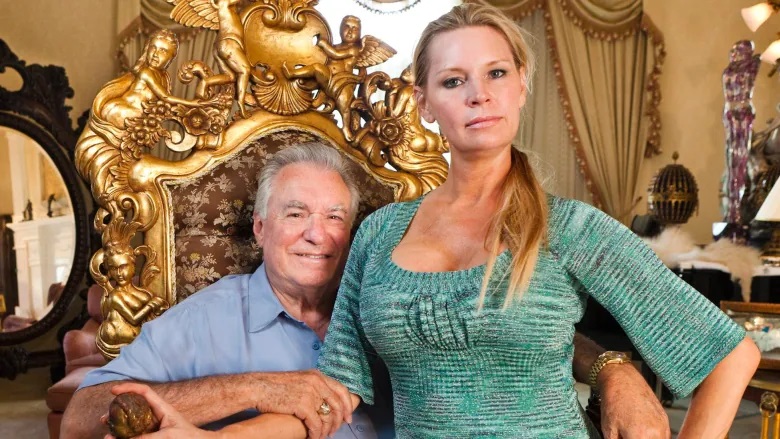

The film begins with a photo shoot presenting Jackie and David Siegel. They are happily married (his third, her second). She is forty-three, he is seventy-four. He says when he first saw her, he thought she was “gorgeous,” and he quickly continues that she has a “good heart” and is a “good mother.” She says it is nice to be adored. Siegel has accumulated a lot of wealth as founder of the largest and most successful time-share operation in the world. Neither claims to have set out to build the largest house in America. They both just started thinking about what they wanted and, by the time they had pooled their dreams, “it just sort of happened.”

What happens next—the global financial crisis of 2008—changes everything. Many great documentaries (Shut Up and Sing; My Kid Could Paint That) start out being about one thing and benefit from the fact that the documentarian is there when external circumstances change the story arc. Greenfield could have made this into a scathing indictment of people who, at times, appear jaw-droppingly oblivious to the implications of the words coming out of their mouths or of the cognitive dissonance most will feel when comparing their words to what is happening on screen. In a Q&A, Greenfield expressed discomfort at the practice of documentarians being self-reflexive and inserting themselves into the narrative. While her voice is heard at times, particularly in interviews with David, she clearly prefers to let the subjects speak for themselves. That’s not to say that the film is never editorial. Some of the edits are too on the nose not to be invite eye-rolling; Siegel’s adult son shares that his father’s creditors had the gall to suggest the family move into an “apartment” when Siegel’s CFO complains that he does not have enough money to make expenses and the film cuts to Jackie eating a $2,000 plate of caviar that she has “gifted” herself for Christmas. When David waxes about how one of the main reasons he loves Jackie is because she is such a good mother, the film cuts to the nanny giving one of the youngest children a bath.

While Greenfield does spotlight some of the more egregious examples of the Siegels’ obliviousness, she is too perceptive and probing to be satisfied with a caricature or celebrity hatchet job. The Siegels engender empathy to the extent they have what addicts–and Siegel himself uses the addiction metaphor to describe the relationship between consumers and easy credit—call moments of clarity. The rhetoric of self-justification and moral evasions is certainly present. “The bankers” forced them to lay off workers and refuse further loans, in Siegel’s mind, because they would prefer to collect the properties, particularly a Las Vegas time-share, that are under water but have significantly more equity tied up in them than what can be converted to liquid assets. They also, though, have moments of brutally honest self-criticism and self-doubt. Jackie admits that having kids without a nanny is a very different experience than having kids with a paid support system. When asked during a time of economic stress if he takes strength from his marriage David says, simply, “no.”

If The Queen of Versailles were merely a film about proud or foolish people getting their comeuppance, it might be pleasurable (to some) but it wouldn’t be great. And I would argue that it is great. Because, really, what it is about is something more universal. It is about living with the consequences of decisions made in the past. It is about how experience is, at times, a cruel and indifferent teacher. It makes all but the most blind or the most lucky more cognizant of the little lies we tell, the little rationalizations we make, the little compromises we hide, to convince ourselves that we are the people we want to be rather than the people that we are. One of the great spiritual dangers of money is that it allows us a great amount of freedom, and few of us, rich or poor, have developed the requisite maturity, intelligence, and self-discipline to exercise near absolute freedom without doing ourselves great harm. Perhaps one of the greatest dangers of the freedom that money provides is the way it can stunt the natural development of those qualities so that if that freedom is ever taken from us, the resulting circumstance are a purgatory felt more painfully or a prison more inescapable than it ever would be for the person who never had the money to begin with.

In June of 2015, Jacqueline shared the following update on Facebook:

“It is with great sadness that we ask you to respect our privacy during this tragic time and the loss of our beloved daughter, Victoria. Thank you all for your prayers and for your support.

As more information comes out the family will share it, until that time there is no comment.”