The Way We Speak (Ebright, 2024)

When I was a college undergraduate in the mid-1980s, I participated in a “debate” with the campus Atheist. I didn’t particularly want to do it– at least I don’t remember wanting to do it — but I convinced myself that refusing to participate would “send the wrong message” to …someone.

I remember winning rather handily, by which I mean that all the people who came to hear me stand up for what they already believed told me I did. I would not be at all surprised if my antagonist believed the same for the same reasons. Years later, I had a private conversation with the same guy, and he shared some private things about his past that confirmed my developing opinion that such debates are seldom about theology and even more seldom successful in accomplishing the stated goals of the participants.

Last year’s Freud’s Last Session was the latest attempt to make a movie out of the theological debating game, and while it had a better pedigree, I thought it suffered from some of the same problems as God’s (Not) Dead and the Left Behind franchise. Any depiction of such debates that doesn’t show one side as clearly winning and the other as clearly hypocritical will be received by both sides as unfair and inaccurate. There are a lot of great films about sincere religious people. There are a lot of great films about hypocrites using religion. But rarely are those who are pro-religion clear-eyed enough to concede any flaws in their avatars’ arguments or executions. And rarely are those who are anti-religious fair-minded enough to concede that religious arguments and those who make them could be anything other than idiocy.

“What if she’s smarter than you?” someone asks Simon Harrington (Patrick Fabian) about the young Christian author and speaker who is called on to debate him at the beginning of the movie. “Not a chance in hell!” is his closed-minded reply. To be religious is to be dumb. To be religious and not admit that you are dumb is to be intellectually dishonest.

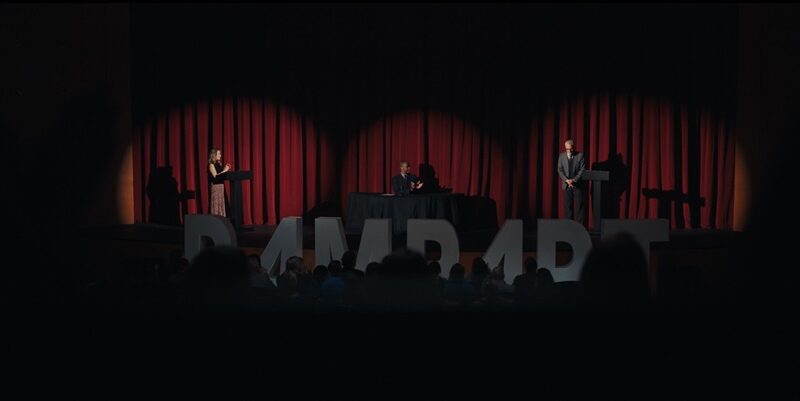

At this point, I was ready for either of two things to happen. Either the film would reveal him to be the intellectually dishonest hypocrite who did not play fair and used specious debate logic to vent his personal feelings or she would be revealed as a charlatan. The only thing traditional movies are less comfortable with than a clear winner in an Atheist/Christian debate is a muddy line between victim and victimized. But to his credit, writer/director Ian Ebright gives us something other than just characters (who we may or may not agree deserve it) getting a forensic comeuppance. If there is a dramatic weakness on display, it may be that the “pox on both your houses” perspective seems unlikely to be embraced by either side as entertaining, even if there may be a target audience out there who is tired of both these camps.

When I made a comparison to Best of Enemies on my Letterbox’d page, Ebright (or someone claiming to be him) affirmed that the documentary was an inspiration for this film. Given that The Way We Speak begins with a Gore Vidal quote, is shaped around a series of debates, and climaxes with a viciously crass personal insult by one of the debate participants, this reference wasn’t too hard to spot. What might be less immediately apparent to those watching the film (but is born out by Ebright’s comments, especially in the press kit), is that he is more interested in political divisions than religious or theological ones.

That’s probably why the film worked for me. Divisiveness and polarization are human traits that are hardly limited to discussions of religion. Too often, we act as though the fact that religious discourse leads to hateful rhetorical or uncivilized action as saying more about it than the people who wield it. Maybe there is a grain of truth in that stereotype since some topics provoke emotions lying closer to the surface and thus more quickly spiral out of control. Don’t talk about religion or politics at the dinner table.

But the problem with just making some topics off limits for debate in polite society is that it simply represses the aggressiveness, arrogance, and hypocrisy of humans rather than addressing them. These are humanity’s besetting sins, not found to a greater or lesser degree in Christians, Atheists, or agnostics. Maybe that’s a backhanded knock on Christians (shouldn’t we be better if the love of God is in us?), but it may even be plausible to read one of the characters in the film as better than the other just so long as we don’t try to suggest that that moral, emotional, or civil decency correlates in any way to intellectual acumen.

It’s been a long time since I’ve quoted scripture in a movie review, so I’ll just conclude by saying that I appreciated the title, The Way We Speak. The political polarization of our era is built on and fueled by the way we speak to and about one another. James 3:6 says, “[No] human being can tame the tongue. It is a restless evil, full of deadly poison.” The older I get, the more I am struck by the discrepancy I perceive between which “sins” the Bible classifies as being most insidious and destructive and which sins some Christian cultures choose to emphasize. Speech, whether it is deceitful, harmful, or both, seems to me to be treated far more seriously in the Bible than we treat it when we hear our poets, priests, and politicians abuse it.

One principal reason for this is that speech is often fueled by anger, and anger is the emotion that most often allows us to justify to ourselves things we know are wrong. Ebright’s film understands this all too well. Both of the characters, I think, know they are wrong when they say the things they say. It turns out that allowing some imperfect people room to reflect on their imperfections is more dramatically (and spiritually) interesting than debating which of them is more imperfect than the other.