God & Country (Partland, 2024)

For nigh on ten years now, I have been telling all of my friends, most of my acquaintances, and anyone else who would listen: “This isn’t Christianity. This is not what I believe. This is not what most Christians I know and interact with believe.”

So why am I not more enthused about a film that finally echoes that sentiment? That shouts it at the top of its lungs so that everyone can hear?

I wish I knew.

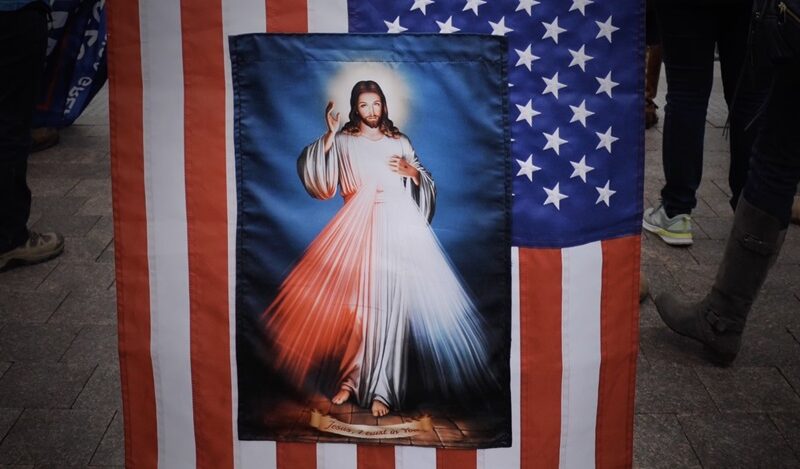

I suspect part of the answer is that while God & Country is relentless and emphatic in answering the question “Is Christian Nationalism actually Christian?” (spoiler alert: no), it is less interested in offering a response to it or an explanation for it. We get that the Christian Nationalists used to be a fringe element of the Republican party and have now taken it over. But what allowed for or expedited that evolution is less clear. Easier by far to wring our hands yet again at those who sincerely believe the distortions and obfuscations than to name names when talking about those who recognized the gulf between Donald Trump’s ideology and that of New Testament Christianity and chose to support him anyway.

There are a couple of new tidbits here, even if most of the film’s points are fairly self-evident. I had not heard, for example, of the so-called “Cyrus Anointing” that equated Donald Trump with an Old Testament Persian ruler who liberated the Israelites by conquering Babylon. It makes some sense, maybe, I guess, to look for Biblical precedence of a ruler who is sympathetic to God’s chosen people even if he isn’t one of them. Though as with all providential worldviews (those that hold that all or certain events are ordained by God), the question of why a deity who is all-powerful and can do whatever He wants is unable to raise up or appoint a godly ruler to look over His people is never really a question broached.

The film also does a credible job of laying out the argument that it was school segregation, not Roe v. Wade, that galvanized the prototypes for Christian Nationalism. But honestly, here the film veers a little too close to oversimplifications and the sorts of either/or thinking that it mocks its targets for preaching.

Ultimately, though, I think the real source of my ambivalence was that I could not fathom who the movie was for or what it hoped to accomplish. Those who practice Christian Nationalism are shown, pretty damningly, as incapable of even hearing, much less responding to cogent arguments. Those who don’t most likely need far less persuasion that Christian Nationalism is wrong than that Christianity still exists as a viable social and cultural force for good in America, capable of not just speaking out against Christian Nationalism but offering an alternative to it.

I’ve long insisted that a film or filmmaker is not required to solve a problem as a condition of being allowed to document it. So I can’t fault God & Country for simply shining a light on an inconvenient truth about the state of religious practice in the current cultural moment. But neither can I get particularly excited about yet another dire warning about how close we as a nation or world are to losing democracy. It’s not that I think the warnings are overhyped, but absent a call to action, what is the difference between an alarm siren and a canary in a coal mine?

When I was in my young adulthood, I heard a sermon illustration many times about a famous preacher who gave the exact same sermon to his congregation several weeks in a row. When the congregants complained and asked the preacher when he would give a new sermon, his reply was that he would preach something new when they demonstrated that they had heard and acted on the old. Jesus is reported in the New Testament as saying that the greatest commandment is to love God with all our hearts, souls, strength, and minds, and that the second, equally important, is to love our neighbors as ourselves. What does that have to do with the film? Not much, really. Just didn’t want to let this review of what Christianity is not go by without offering up an opinion about what Christianity actually is.

I found Bad Faith (also released this year) to be a bit more fleshed out than God & Country. There’s so overlap, for sure, but the context Bad Faith provided was more impactful for me.