2022 Top 10

Covid didn’t kill the movies, at least not for me. But as it did with most other non-work activities (especially sports viewing), it highlighted how much of that activity was based on habit rather than choice. I watched fewer movies in 2022 than I have in a long time, and it’s taken me until February to reconcile myself that my list of annual favorites isn’t going to change substantively.

That says more about me than it does about the quality of the movies released in the calendar year, so here’s the annual disclaimer that this is a list of personal favorites rather than an argument in support of a tenuous claim that the films here are the objectively best. I would think and hope that there is a correlation between the amount I enjoy a film and how good it is, but there are other factors in play.

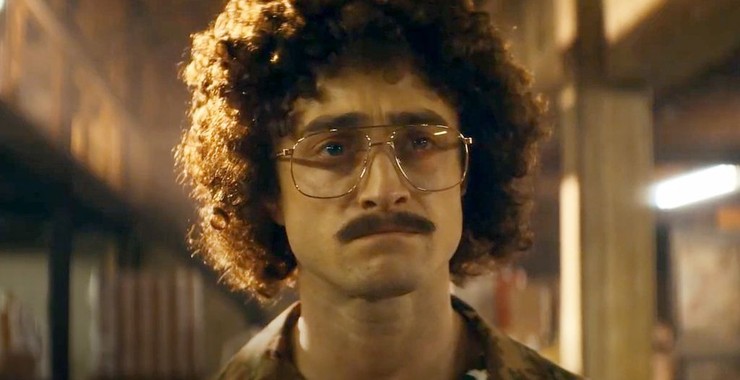

10) Weird: The Al Yankovic Story

The first adjective out of my mouth when describing Weird was “fun,” and I haven’t had fun at the movies in a long time. The film sent me to YouTube to revisit old favorites and catch up with later songs I had missed because I stopped knowing what Yankovic was parodying. I reached out to my 80s friends to reminisce about our own attempts to emulate the master with songs that live only and will die with us — “King of Tron” and “I’m Bill Scanlon.” I also found a wonderful interview with Coolio before he died recognizing he was wrong for his manufactured beef with Weird Al. That sent me to watch the video for “Gangsta’s Paradise,” which I realized, belatedly, is a pretty great song. I think Weird Al’s genius is that the parody was never hostile. In an age of Internet trolls and politically weaponized emotional cruelty, it was fun to be reminded of a time when it was okay to be silly and where we might even, on occasion, dare to be stupid.

9) Prey — Dan Trachtenberg

I didn’t watch this film until the end of the year, distracted by the inevitable, unsurprising (and wrong), complaints about wokeness or feminism or who knows what. Prey is a modest movie, but I very much appreciated that in an age where franchises churn out indiscernible duplicates of their predecessors, it manages to be faithful to that which came before while exploring new aspects of the story. I was particularly interested in the idea that the Predator was vulnerable because he didn’t see Naru (Amber Midthunder) as a threat. That idea that a superior force can be toppled by a combination of luck, determination, and the weakness of its own blind spots is culturally and historically ironic as we consider what is in store for Naru and her people and in what ways the Predator/Prey relationship is archetypal.

8) The Glass Onion — Rian Johnson

When I saw the Glass Onion at Filmfest 919, I invited Edward Brown to review it because I found myself indifferent. As the film collected buzz, I wondered if the viewing situation impacted me more than I had realized. Now that I am in my late 50s, doing three to four movies a day at a festival or a dozen in a week is a different proposition. What used to be a stimulus to a bored imagination becomes a drain on an already weary body. Here’s what I can say about the film for sure: it’s funny. Perhaps not side-splittingly so, but there is something deeply satisfying in seeing Edward Norton embody rich, smug, arrogance and be revealed to be rich, dumb, and arrogant. I know, too, that I’ll happily go see the next one. Perhaps it was Benoit Blanc’s admission that he, too, needs intellectual stimulation to keep from falling into a depression that won me over. The absence of movies for a period of our lives had more than just commercial and financial consequences. Welcome back Benoit; welcome back Rian.

7) The Inspection — Elegance Bratton

Sometimes you love a movie for a single scene. I’ve written about The Inspection before, and like several films on this list, it might be accused of being generic in the most precise sense of the word; it has many of the conventions of the boot camp genre. It also has some new twists, and those revitalize the genre and lend the story an authenticity that the outsider’s indulgence in genre conventions often lacks. For me, the scene in which, one by one, several candidates refuse an order from a bullying drill instructor is as thrilling as any cinematic example of the vulnerable defying the powerful. It is thrilling in part because the outcome is by no means assured and yet it is, in its way, entirely plausible. The rest of the film may not reach the same heights, but when it is at its best, The Inspection has the capacity to make us not just hate the abuser (that’s actually quite easy to do in movies) but also to love the acts of compassion and resistance.

6) After Yang — Kogonada

After Yang reminded me a lot of Ex Machina. Its strength is in the writing. I wanted to like it even more than I did, but I wished it had been slightly more . . . cinematic. The story of a patented artificial intelligence named Yang is all the more heartbreaking because, unlike A.I., it focuses on the humans who anthropomorphize it rather than on the artificial lifeform itself. As a result, there is a lot more emotion than one might expect. By raising questions about the nature and values of life outside of the question of abortion, After Yang revitalizes discussions (or even just contemplations) about what it means to be “pro-life.” Anyone who has ever lost something they love that is not human — an object, an animal, a relationship, knows that the pain surrounding death does not require the death of a living organism. It only requires the cessation of a bond between the survivor and the thing he or she loved.

5) Holy Spider — Ali Abbasi

Yes, this film is bleak, but you know what, maybe that’s why I respect it. I would not be the first person to point out in some review of the serial killer genre that the total amount of time the average male spends watching females victimized in screen images is horrific to even contemplate. The very repetition numbs us and in the loss of our ability to be shocked, disgusted, or afraid (of what we might see), we lose a part of ourselves. For the last several years I have taught a lot of Early American Literature, and so I have thought a lot about the interrelationship between patriarchy, religion, and violence. I’ve thought a lot about how frequently violence is preceded by dehumanization. The formal feature I admire in Holy Spider is that it refuses to dehumanize the victims by turning them into only characters. The actual assaults, the actual killings, have a snuff-film effect, but in refusing to cut away from violence after its beginning, the film ceases to feel safe to watch. What a horrible thing it must be to not feel safe — to never feel safe. A film that can make us feel how deeply demoralizing that must be makes it impossible to not feel at least some empathy for those in the film (and in our lives) that we look past, whose suffering is too often invisible because we fail to see their bodies even whey they are alive.

4) She Said — Maria Schrader

Remember when Spotlight won Best Picture but Tom McCarthy was slighted for Best Director because it was assumed that there wasn’t anything visually interesting about a journalistic procedural? I actually think there are few things in life more dramatic than people talking, few instances more pregnant with potential than one person in possession of truth and another seeking it. I was not a fan of Promising Young Woman, but I have been a fan of Carey Mulligan dating back to seeing An Education at TIFF. She and Zoe Kazan do something remarkable and underrated in this film. They act with their bodies and not just their voices. They act by and through listening. The weight of the words they hear is conveyed not through the eloquence of the dialogue but through the toll it takes on those who receive it and become responsible for what they do with it. I saw She Said before I saw Holy Spider. I will resist the temptation to compare them as an intellectual exercise because such formal comparisons are too often intellectual evasions. What I will say by means of comparison — and I mean this a compliment to She Said — is that the most obvious difference between the two films (women being killed as opposed to women being assaulted) felt less material than the many similarities (women dehumanized, ignored, silenced, marginalized, disbelieved, and denied an equal status even when it comes to being deserving of human dignity.)

3) Good Night Oppy — Ryan White

There are a lot of downer films on my list, so this little documentary that could, like the robot of its title, brought a disproportionate amount of joy by exceeding expectations. There are large portions of American culture that make science the enemy. We are dismayed by its applications (bombs and biowarfare) and somehow lose sight of its ability to inspire and challenge us. Parallels abound between this film and After Yang, and it was only after watching this film that I warmed to the drama. Because I cared about a rover. Because I saw it not as human but as a symbol of something human — determination, courage, the miraculous ability to take another step even when we don’t know where we are going or suspect that there is no way we could ever get there. Good Night Oppy evokes some of my favorite life lessons. Don’t despise the little things. The accumulation of small habits can result in great changes. Failure is change reaching for success. Like Prey, this movie suggests that our beliefs and values are passed on through generations and that key moments in our lives happen not just at the end of journeys when our lives are poured out but at the moments when we embark, deciding what it is worth pouring our lives out for.

2) The Woman King — Gina Prince-Bythewood

Like She Said, The Woman King reminds us eloquently that strength and pain can coincide. It is one of life’s greatest mysteries that the quality we most often desire is that which allows us to endure more of what we would gladly do without. Viola Davis is remarkable here, and — I cannot stress this enough — credible. The very first review I ever wrote (for my college newspaper) was for James Cameron’s Aliens, and I argued in it that Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley was more human and thus more relatable than Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo. Perhaps that is why I find myself appreciating films with female warriors more than male ones. The latter are often idealized. In their indestructible nature, we might find wish fulfillment or fantasy. But they aren’t real. In the coexistence of strength and pain, I find something equally aspirational but also something hopeful because it seems possible.

1] The Banshees of Inisherin — Martin McDonagh

What if you woke up one day and the person you thought of as your best friend said they wanted nothing more to do with you? That you were unworthy of their friendship and an impediment to their personal or professional life goals? Friendships don’t come with the legal sanctions of marriage nor the institutional expectations of family. Would you be hurt? Angry? Would you fight for the friendship or simply fight back? The Banshees of Inisherin is a cynical film, and I confess on first viewing I mostly misread it. I wanted it to be an allegory about how we try to refuse God’s presence in our lives and how the Hound of Heaven will not be sent away. Perhaps it could be made into that, but the film’s last act makes such a reading all but impossible. The better Biblical allusion, if Biblical allusions there must be, is to the book of Ecclesiastes, which suggests that whatever we are tempted to put at the center of our lives — family, friends, work, art, pleasure, reputation — will ultimately fail us. This can make us bitter, as it does Colin (Brendan Gleeson). It can push us to despair, as it perhaps does to Pádraic (Colin Farrell) or it can force us to reevaluate the place of the good things in our lives that were never meant to be at the center. I want to be clear about one thing. For all its dark humor, The Banshees of Inisherin is an effing tragedy. I say that because Colin is ill and others refuse to confront that fact, instead categorizing his sickness as cruelty, eccentricity, or some sort of dumb wisdom. The closest the film gets to holiness, at least for me, is a speech in which Pádraic extolls the virtues of being “nice.” It is uncomfortably near the truth, so it is, of course, ignored and parried with easy intellectual jibes and rhetorical philosophizing. At the heart of The Banshees of Inisherin is a portrait of sin and ugliness in many forms. We are comfortable with that word when applied to sadists like Tony Soprano or Hannibal Lecter, and many a tragedy has been filmed about potentially good people who were warped by their vices into cruel parodies of themselves. Fewer have been filmed that depict those warped by their virtues, wrongly applied or understood. Perhaps this is one of them.