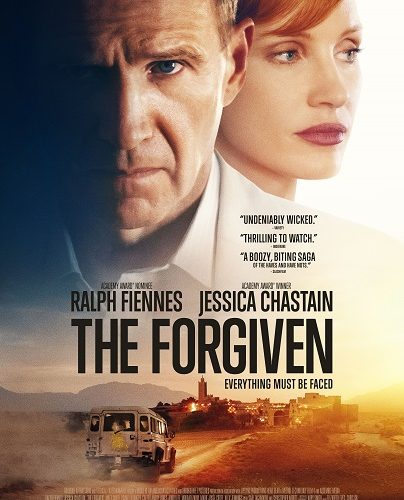

The Forgiven (McDonagh, 2021)

Had I seen The Forgiven without opening credits, I probably would not have immediately associated it with John Michael McDonagh’s Calvary. It’s a long way from the coasts of Ireland to the desert of Morocco.

But the movies are thematically similar, examining the intersection between private and corporate oppression. There are, of course, differences. In Calvary, the underlying trauma of a boy raped by a Catholic priest is representative of a broader problem. In The Forgiven, the plot revolves around an automobile “accident” in which a colonial driver kills a Moroccan local. The most important difference, however, lies in the culpability of the protagonists. In Calvary, the priest is not personally guilty of the underlying crime. He is pursued and punished for the sins of the larger group he represents. In The Forgiven, the driver (Ralph Fiennes) does kill the boy. To paraphrase his own confession — he was distracted (arguing with his wife), reckless (driving too fast), and impaired (drinking).

There are also differences in the films in terms of who is seeking acknowledgment for wrongdoing and what such acknowledgment would signify. At their core, though, both films present men whose individual actions (or inactions) become inflection points for understanding the rage of an entire class of victims.

Calvary is the better film of the two — by a wide margin. The introspection and erudition of its central character lend themselves to the gravitas of the material more than do the qualities of an outwardly flippant, debauched pseudo-vlllain who turns out to have more principles than some of his peers who talk gentler but whose racism or diffidence runs deeper.

But one need not make the near-perfect the enemy of the good. If the worst thing I can say about The Forgiven is that it is not as good as Calvary, the best thing I can say is that it is nevertheless a serious film about conflicted characters wrestling with moral questions — something we could always use a bit more of these days.