Favorite Film Series: Claire’s Knee (Rohmer, 1970)

Claire’s Knee is my favorite film from my least favorite year of film history.

Such pronouncements are tedious provocations, usually to be avoided. But it feels appropriate here since the fifth of Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales often feels as though it deliberately provokes and because many cinephiles find Rohmer as tedious as I find some of the more celebrated films of the era. Arthur Penn’s Night Moves has a jab, which I’ve often misattributed to Pauline Kael, equating looking at a Rohmer film to watching paint dry. Kael’s barb was to call Rohmer the director of “semicomic triviality.” As a fan of Rohmer’s, I don’t even find the Kael comment that far off. “Semicomic” is only a jab if someone is trying to be hilarious (see, for instance, Woody Allen), and “triviality,” I have to think, applies only really to Kael’s valuation of Rohmer’s aesthetic and not the (non-) importance of his subject matter.

Claire’s Knee is about desire, which is a timeless theme, and about how we justify acting on our desires, which is a very timely one.

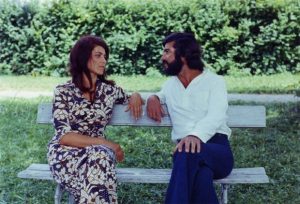

Jerome, perfectly played by Jean-Claude Brialy, looks and feels temperamentally the opposite of the introspective and insecure protagonists of film and literature who typically lust after underaged girls. He’s ruggedly handsome, direct and articulate about his feelings, and seemingly free of religious or social taboos surrounding who he has sex with. He’s engaged to be married but on a summer holiday and not at all concerned about fidelity. Within a day of meeting a former lover with a sexually curious and aggressive teenaged daughter, Jerome’s pronouncements about the impact of his engagement have shifted from “I don’t look at the ladies anymore” to “we’ve both had affairs.”

Laura, the teenager in question, isn’t exactly what Humbert Humbert calls a nymphet. For one thing, Nabokov’s character reserves that designation for girls between nine and fourteen. For another, Humbert claims for them an almost bewitching, demonic power that Laura doesn’t possess. She is frank, sexually curious, and appears herself intoxicated by sexual banter and anticipation. Her mom claims she is in love with Jerome, but he insists that she is just playing a “dangerous game.” It’s a game because she thinks she is in control but it is dangerous because she isn’t and because she doesn’t really know or understand her own desires, much less his. And by removing the social and moral taboos against their age difference, Laura and her mother are removing any safeguards, as feeble as they may be, against Jerome’s own lust should she change her mind…which, of course, she does.

Most films, I suspect, would end at this film’s half-way point. The arc of Laura’s and Jerome’s flirtation works as a self-contained story, and Jerome’s restraint at the point where Laura is most vulnerable, while not exactly a redemption arc, could be read as the victory of conscience over (post)modern amorality. But just when we think we’re almost done, Rohmer raises the stakes. Jerome’s attention shifts from Laura to her step-sister, Claire, and the interrogation of desire probes a bit deeper.

Most films, I suspect, would end at this film’s half-way point. The arc of Laura’s and Jerome’s flirtation works as a self-contained story, and Jerome’s restraint at the point where Laura is most vulnerable, while not exactly a redemption arc, could be read as the victory of conscience over (post)modern amorality. But just when we think we’re almost done, Rohmer raises the stakes. Jerome’s attention shifts from Laura to her step-sister, Claire, and the interrogation of desire probes a bit deeper.

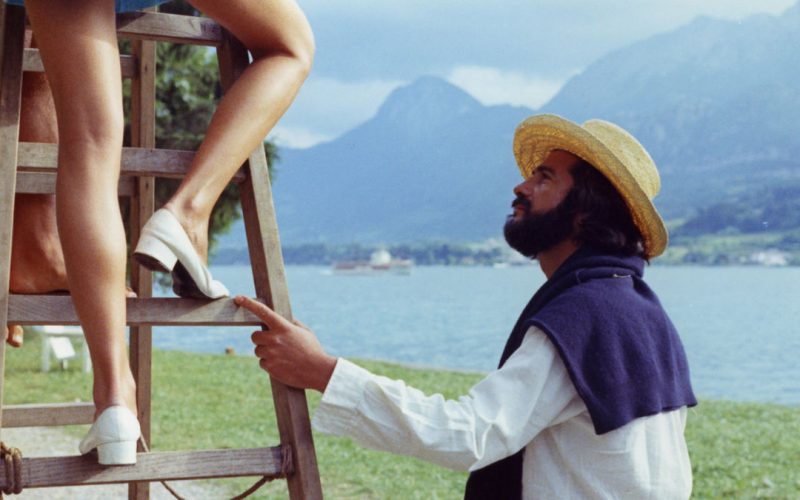

The most obvious difference between Jerome’s flirtation with Laura and his desire for Claire is that Laura is a knowing and (to the extent any teenager can be) willing participant while Claire is not. Jerome’s unwanted advances towards Claire are sexual even if they don’t involve intercourse, and they render suspect his justifications (such as they are) of his conduct with Laura. With Claire, Jerome is reduced to Humbert-like protestations of the bewitching, irresistible power of Claire’s body and his desire to touch it.

That Jerome is aware of just how traumatic his caress of Claire’s knee is can be heard in his recounting of the event to her step-mother, Aurora. The text is from Rohmer’s prose novella, included with the Criterion Collection set of Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales:

“So I put my hand on her knee; it was a rapid, assertive gesture that gave her no time to react. All she did was look at me–indifferently, I think; in any case, with hardly any hostility. But she said nothing. She didn’t remove my hand; nor did she move her leg. Why, I couldn’t say. I don’t understand. Or maybe I do. You see, if I had tried to caress her hair or forehead, she would certainly have reacted with some classic, instinctive gesture of self-defense. But what I did took her by surprise. She probably assumed it was the initial tactic of an assault that was to follow. And when it didn’t, she was reassured. What do you think of that explanation?”

There’s a lot to unpack in this paragraph. I will start with the somewhat banal observation that a film is not a text and vice-versa. In Rohmer’s film version of his own text, we don’t simply have Jerome’s account of the event, we have the camera’s actual record of it. And Claire’s look is in no way indifferent. She has been, and is, weeping due to Jerome’s cruel flaunting of the fact that her boyfriend is cheating on her. When he caresses her knee, she looks at him and stifles another sob. The look may not be hostile but it is certainly miserable and is in no way indifferent. In the text, Jerome, who prides himself on his cavalier, brutal honesty, equivocates greatly. He immediately qualifies “indifferently” with “I think,” admitting she “said nothing” to indicate what she was feeling. The “hardly any” that qualifies “hostility” directly contradicts the claim made in the previous sentence that she was indifferent.

The most damning phrase, though, is “assumed it was the initial tactic of an assault that was to follow.” Jerome justifies the caress because it stops short of being a familiar enough form of assault to provoke a “classic” gesture of “self-defense.” He doesn’t see the grope itself as an assault–though he acknowledges it was unwanted touching of a sexual nature–much less does he see anything wrong with the emotional battering and manipulation that precedes it.

That Rohmer presents Jerome as a cad and the sexual liberation of his and Aurora’s generation as a destructive lie, is enough for me to favor Claire’s Knee over scores of films that champion sexual freedom and blame human unhappiness on the puritanical taboos themselves rather than on the taboo actions that for generations were almost universally condemned. But the film has a final scene which extends beyond the simple binary of victims and victimizers and hints at deeper and more complicated moral questions.

After Jerome leaves, Aurora overhears snippets of a conversation between Claire and Gilles, the boyfriend whose lies Jerome used to break down Claire’s emotional defenses. Rohmer writes in the text that “Gilles’ explanations seem little by little to get the better of Claire’s accusations.” He concludes the novella with the observations that “the boy’s left arm is around Claire’s shoulder, and his right hand is caressing her knee.” (In the film, the pair is seated on a bench, and we cannot actually see the caress.

What are we to make of this repetition? It’s hard for me to avoid the implication that sexual boundaries are learned behaviors and now that Jerome has broken that boundary Claire finds it easier to repeat the pattern of letting a disingenuous male define the terms of their relationship. The scene reminds me of an early exchange in Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity (later made into a movie by Stephen Frears). In it, one of Rob’s former girlfriends explains the reason she had sex with a subsequent boyfriend and not him was not that she loved the other boy more but because Rob’s constant attempts to have sex with her gradually drained her resistance and she eventually found it easier to simply capitulate in her next relationship.

The use of the term “boy” in the text is striking, because if we are to insist that Laura’s earlier complicity is irrelevant to Jerome’s culpability because she is (socially and emotionally if not biologically) still a “girl” then are we not also forced to excuse Gilles on the grounds that he is only a boy? More dicey still are the implications of acknowledging that Claire’s behavior in the present moment might be rooted in behavior learned and trauma received in the past. But if that is true of Claire, is it not equally true of Jerome and Aurora? Are not their sexual attitudes socialized? Do we care what happened to them that made them the way that they are?

In the novella, Aurora asks two questions that seem to me to lie at the heart of Rohmer’s narrative: “As for what she thought, what does it matter to you? I see you there in the semidarkness of the boathouse, a couple sculpted for all eternity. Who gives a damn about your thoughts?”

The first question is directed to Jerome: why does it matter to him what Claire thought? If sexual taboos are just remnants of repressed culture and there is no proscribing God to judge him, what difference does it make whether Claire was feeling hostility or not? If he justifies his own conduct to himself by saying he is psychologically (or even evolutionarily) unable to control his lust, then of what consequence are the consequences of his actions? If God is dead, everything is permissible.

The first question is directed to Jerome: why does it matter to him what Claire thought? If sexual taboos are just remnants of repressed culture and there is no proscribing God to judge him, what difference does it make whether Claire was feeling hostility or not? If he justifies his own conduct to himself by saying he is psychologically (or even evolutionarily) unable to control his lust, then of what consequence are the consequences of his actions? If God is dead, everything is permissible.

The second question is also directed to Jerome, but it has wider implications for the reader/viewer. Do motives matter? Do reasons matter? Or are actions the only things that count? Aurora is probably pretty confident–as am I–that Claire would not give a damn about Jerome’s “thoughts.” On an abstract level, a victim may be aware that the person victimizing her has his perverse reasons for doing so, but hardly ever does that awareness rise to the level of understanding or excuse. The victim just wants the perpetrator to stop. (Here, I confess, I think not of High Fidelity but of Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady: words, words, words / I’m so sick of words / I get words all day through / First from him / Now from you / Is that all you blighters can do?)

Just as Jerome’s equivocations in his speech hints at a repressed but still existent guilt that no amount of social license can expunge so too does Aurora’s reply suggest a repressed but deep-seated anger at the cultural misogyny in which she participates and to which she is shepherding her daughters. I suspect that for some critics and viewers, Aurora will represent the projection of a male author’s wish fulfillment — she is a beautiful, available woman who tells herself she is in control and tells men that they are free to gratify their own desires however they wish so long as she may do the same. The more I watch Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales, however, the more I tend to see his female characters as complicated and complex rather than simply interchangeable objects of male desire. For one, they seem less self-deluded then the men even if they are no less unhappy. For another, they resist in countless ways both big and small, the male attempts to define them. Jerome can say what he wants about Claire, her tears are a real, observable fact, which like the sobs of Delores Haze that Humbert Humbert hears through the bedroom door, tell a very different story about what she is thinking than the one that a male narrator weaves about her.

One Reply to “Favorite Film Series: Claire’s Knee (Rohmer, 1970)”