The Criterion Collection: All That Heaven Allows

Ken’s Note: As most cinephiles could tell you, July is one of the month that The Criterion Collection offers its semi-annual 50% off sale. Given the label’s array of titles, taking advantage of that sale can be daunting. I’ve asked friends and colleagues to make write up one of their favorite or newly acquired Criterion discs. In this column, Colin Stacy weighs in on Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows.

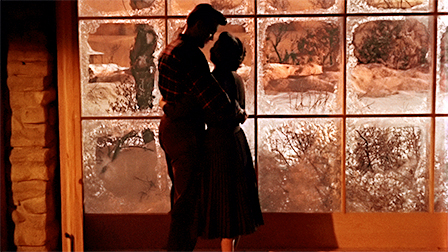

It’s hard to imagine a film more befitting of the careful touch of the Criterion Collection’s preservationists than Douglas Sirk’s Technicolor-blasted tale of forbidden love in the American suburbs, All That Heaven Allows (1955). A classic Hollywood melodrama, this film deals in the emotional currency of bold coloring, sumptuous lighting, and emphatic orchestral arrangements. Sirk pushes the boundaries of cinematic artifice by turning the theater (or living room) into a pulsing organ. Its pastels are meant to burst. Its light should glare while its shadows consume. The score is set to erupt often, with timely, flamboyant sentiment. As a document of the domestic time bomb that was America in the 50s, All That Heaven Allows’ visual syntax is perfectly unified. Sirk and cinematographer Russell Metty glean the emotional truth from every layer of the filmmaking process to create not only a reflective portrait of a now bygone time but an adroit text of unprecedented purity, an ode to craft.

It’s hard to imagine a film more befitting of the careful touch of the Criterion Collection’s preservationists than Douglas Sirk’s Technicolor-blasted tale of forbidden love in the American suburbs, All That Heaven Allows (1955). A classic Hollywood melodrama, this film deals in the emotional currency of bold coloring, sumptuous lighting, and emphatic orchestral arrangements. Sirk pushes the boundaries of cinematic artifice by turning the theater (or living room) into a pulsing organ. Its pastels are meant to burst. Its light should glare while its shadows consume. The score is set to erupt often, with timely, flamboyant sentiment. As a document of the domestic time bomb that was America in the 50s, All That Heaven Allows’ visual syntax is perfectly unified. Sirk and cinematographer Russell Metty glean the emotional truth from every layer of the filmmaking process to create not only a reflective portrait of a now bygone time but an adroit text of unprecedented purity, an ode to craft.

Throughout the many interviews included on this teeming Criterion set, Douglas Sirk regularly uses the word “handwriting” to convey his vision of filmmaking. In an excerpt from the BBC documentary Behind the Mirror: A Profile of Douglas Sirk, he mentions how poor of a story All That Heaven Allows was. It was nothing, he says, yet he was allowed the freedom to put a lot of his own “handwriting” into it. He expounds his philosophy even further on the French television program Cinéma cinémas saying that a film’s language is not found in the story but in the light[ing] and the touch. The handwriting is what counts. And as far as modern filmmaking goes, there aren’t many who have better utilized the medium like Sirk. Sure, there are those who can gab incessantly with the form, but Sirk’s language — romanticized and brash — avoids cinematic hyperbole. His “handwriting” is among the most precisely effective the medium has seen.

In All That Heaven Allows, Sirk and Metty’s detailing of the Northeastern suburban life of widowed Cary (an elegant and dignified Jane Wyman) is hyper-meticulous. Her house is possessed by the paraphernalia of the bourgeois, from the wet bar where her son crafts devastatingly inane martinis to the marbled mantlepiece where her late husband’s golfing trophy sits ensconced like a patriarchal throne. She rarely goes out to country club soirees with her housewife-bestie Sara. And as a widow of a certain age, she’s pursued — at snail’s pace — by a family friend, a romance that feels born of the obligatory desperation of a lonely gentleman looking at 70. Cary is entrapped by the mise-en-scene of residential malaise.

In All That Heaven Allows, Sirk and Metty’s detailing of the Northeastern suburban life of widowed Cary (an elegant and dignified Jane Wyman) is hyper-meticulous. Her house is possessed by the paraphernalia of the bourgeois, from the wet bar where her son crafts devastatingly inane martinis to the marbled mantlepiece where her late husband’s golfing trophy sits ensconced like a patriarchal throne. She rarely goes out to country club soirees with her housewife-bestie Sara. And as a widow of a certain age, she’s pursued — at snail’s pace — by a family friend, a romance that feels born of the obligatory desperation of a lonely gentleman looking at 70. Cary is entrapped by the mise-en-scene of residential malaise.

Enter Rock Hudson’s town gardener, Ron Kirby. He’s young, hulking, and quiet. He’s been tending her yard for years, but she’s only noticing him now. Since her husband’s dead and all. What starts as a simple coffee-fueled conversation during a work day soon turns to love. Kirby, the tree-loving, stalwart trunk of a man whose sole religious tome is Thoreau’s On Walden Pond, pursues Cary like this good soapy suburban tale calls for. It’s the story of the widow and the gardener, the suburbanite bird and her evergreen tree. But soon the town is at the doorstep, ready to stand scandalized by the forbidden love.

While the story makes for great entertainment (though not as delicious as the pulpy psycho-violence of his next film Written On The Wind), the handwriting yields much more depth than typical soap fair. Sirk wanted to fill the cheap stuff with meaning, as he says in the BBC doc. He does so by literalizing the emotion of his characters while allowing what he was saying to play out more subtly. The desires of his characters are transmuted onto their clothing, the walls of their homes, and in the lighting shining upon them. But his camera moves in a more investigative way, at once observing these lives with simple neighborly fascination yet diving beneath the surface by pressing into the emotional cracks. As the sets, lighting, costumes, and objects tell the emotional tale, Sirk finds the meaning in the frames.

He thought of mirrors as a medium of getting to know oneself, which is why his films are filled with them. The mirrors and other frames in All That Heaven Allows allow us to peek into the interiors of his characters’ lives, most significantly Cary’s. One scene begins with the shot of a tree branch given to her by Ron. The camera slowly tracks backward to show it in a vase upon her vanity where she studies herself in the mirror. Instead of moving on as Cary’s attention is diverted, the camera stays fixed on the mirror as we see her children walking into the room to greet her. The life she desires sits upon the table in a vase while the one she is trapped in remains framed by an unmoving mirror. Later, it’s her reflection in a television screen which will epitomize her imprisonment, revealing that hers is an encaged life not just being viewed by the audience but by the entire town which holds her hostage in judgment.

He thought of mirrors as a medium of getting to know oneself, which is why his films are filled with them. The mirrors and other frames in All That Heaven Allows allow us to peek into the interiors of his characters’ lives, most significantly Cary’s. One scene begins with the shot of a tree branch given to her by Ron. The camera slowly tracks backward to show it in a vase upon her vanity where she studies herself in the mirror. Instead of moving on as Cary’s attention is diverted, the camera stays fixed on the mirror as we see her children walking into the room to greet her. The life she desires sits upon the table in a vase while the one she is trapped in remains framed by an unmoving mirror. Later, it’s her reflection in a television screen which will epitomize her imprisonment, revealing that hers is an encaged life not just being viewed by the audience but by the entire town which holds her hostage in judgment.

Maybe more resonant than its commentary on suburbia (which has been as effectively skewered since, in movies ranging from Blue Velvet to Gone Girl) is its studied vision of American womanhood. All That Heaven Allows’ theme of the societally defined worth of a woman feels as prescient as ever. Sirk’s subversion of the female’s assumed American domesticity is careful and loving. He’s a director who not only understood human emotion but also the feminine struggle of this time. He saw a woman’s worth and meaning more than defined by the man whose life hers sat adjacent to. In the suburban milieu, Cary is either widowed or scandalized; she is either the mother of two bratty, capricious children or she is the poor soul alone at the cocktail party. She’s allowed no agency in society, which is why her desperation for freedom finds hope of absolution in her relationship with Kirby, a man who represents the life loosed from society. Sirk gives her agency by telling her story, yet he also keeps the intrinsic social perception constricting.

Criterion clearly loves the art of criticism equally as much as the medium. Without their inclusion of one of the finest audio commentaries I’ve ever heard by film scholars John Mercer and Tamar Jeffers-McDonald and essays (in booklet) by critic Laura Mulvey and the German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who took up Sirk’s mantle, I’d have not known how to navigate the depths of the Sirkian melodrama. The final embrace of two lovers was enough to categorize me into the studio’s target audience, yet the criticism included insightfully reveals the falseness of the “happy ending.” Maybe Cary is freed in the end by her relationship with Ron, yet the penultimate shot has her still trapped within a man’s house. At that final moment, she peers out of the biggest frame of the entire film. Like a lipsticked message on a mirror, Sirk’s handwriting precisely reveals the tension of life’s bold emotions and the image which lies beneath.

—

Colin Stacy lives with his wife Heather and son Everett in Dallas, TX where he works for local medical waste company RedAway. His writing can be found at Reel Spirituality and Movie Mezzanine.