The Theory of Everything (Marsh, 2014)

This review originally appeared at Christianity Today. Reprinted by premission. All rights retained.

Warning: This review contains plot spoilers for those that do not know the biography of Steven Hawking.

“Everything” is a big word. In its pristine, unfallen condition, it is a word full of spectacle and wonder. It suggests majesty, mystery, and scope beyond measure. In its pristine condition.

These days “everything” has also come to serve as a lazy synonym for “no one thing in particular.” “What did you like—or not—about the film?” Everything. “What did you not understand about the homework assignment?” Everything. Even, “What do you love about your spouse?” It’s a non-answer, when used that way. And while that usage may not describe Steven Hawking’s theory of everything, it certainly does fit the movie about his life.

The Theory of Everything premiered at The Toronto International Film Festival, the September extravaganza that has managed to schedule the film that went on to win Best Picture for as long as I can remember going there. Last year felt like an early showdown between 12 Years a Slave and Gravity, and indeed both of those films rode strong festival buzz all the way through an increasingly long awards season. There does not appear to be a studio favorite this year. The most anticipated films are from a Frenchman (Godard), a Turk (Ceylan), a Swede (Andersson), and a pair of Belgians (Dardennes). Everything’s director, James Marsh, lacks the prestige of any of those auteurs, but he does have a biopic with the sorts of elements – a selfless and loving spouse, great accomplishments in the face of adversity, a handicapable hero – that the Academy generally loves. And he has already won a golden statute for Man on Wire. I wasn’t enthusiastic about the film, but at least it swung for the fences.

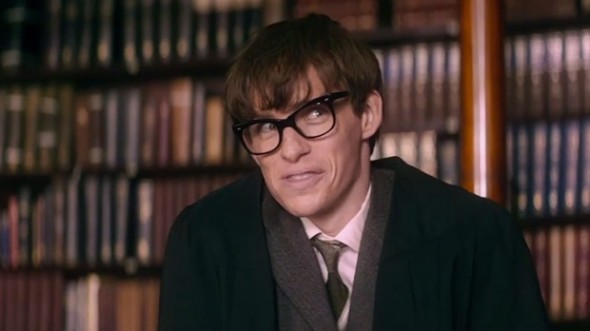

For the first forty-five minutes or so, the film is an inspiring if conventional biopic. Eddie Redmayne finds an actual human being in the legend, and I appreciated that his embodiment of the physicist, while acknowledging some social awkwardness, avoided science-geek clichés. If Steven’s trembling hand seemed as ominous as Camille’s first cough, there was still something fresh and interesting in the way his girlfriend, Jane (Felicity Jones) defied his friends and her family to try to keep her from marrying him. He loves her. She loves him. And she’s stronger than people think.

That is all well and good, but when Steven outlives his two-year life expectancy, “until death do us part” takes on a whole new meaning. I hate to spoil the second half of the film for those who don’t know Hawking’s biography and don’t care to look up his Wikipedia page, but it’s hard to be specific about the film’s weaknesses without focusing on the last act. Suffice it to say that the screenplay is based on Jane Hawking’s book, Traveling to Infinity: My Life With Steven Hawking. While acknowledging the biographical facts that would technically qualify the narrative as a “warts and all” telling, the screenplay bends over backwards to excuse both Jane and (later?) Steven for the choices that end their marriage. He understands that she needs help and occasional relief from being a caretaker. She realizes that he is proud and that fame is a powerful aphrodisiac, particularly to the wounded.

The film leads us up to some monumental domestic choices but then looks away. Jane is left outside the tent of her friend, calling to him. But we do not see her go in. Steven’s eyes wander pointedly to his assistant when she shows him a pornographic magazine and asks if he wants to see more. But we do not see her response.

Should we? In both cases, the culmination of the scenes can be inferred from subsequent actions, just as the presence of Pluto could be known by astronomers before it was actually seen. But if believing is possible without seeing, seeing is something more than believing. These characters have been lionized so much in their own movie, their love proclaimed so vehemently, that these elisions feel like a failure of nerve. Does the film fear we will be shocked? No longer see anything to admire in Jane or Steven? Or does it sense, rightly, that absent an ability to show us Steven working (we see him write one sentence), the second half of film, like Hawking’s career, has been mostly spent disproving the first half? The story in the second half of the film is interesting in its own right, but it gets in the way of the overall story the film has decided to tell in its first act.

By the end, the film has tried so hard to make these characters admirable that it ends up applauding them the most when they are at their worst. The atheist throws his longsuffering wife a bone right before he leaves her by acknowledging God’s existence, but he then meets with his colleagues and says, no, we’re just slightly advanced primates. Still, he insists, we can make little kids in our own image, so we’re sort of god-like ourselves, and that’s almost as good, isn’t it? The film’s centerpiece explanation of cosmology comes in the form of a metaphor regarding peas and potatoes that Jane uses to explain the alleged conflicts between quantum physics and relativity. (Yeah, I have no idea what that sentence means either.) Einstein’s famous quote about God not playing dice with the universe is cavalierly dismissed as evidence that he wasn’t smart or brave enough to face the implications of quantum physics. And Jane recites Genesis 1, leaving God out of it and proclaiming that “In the beginning was [were?] the heavens and the earth…”

It’s not exactly the atheist response to God’s (Not) Dead, but those two films share a condescending smugness towards their competing worldviews that makes me wonder if Christian audiences will much care that the believers in this movie—warts and all—actually act more lovingly than they typically do in the films designed to showcase how superior Christians are to everyone else.

Caveat Spectator

The Theory of Everything gets aPG-13 rating for “suggestive material.” At one point Hawking’s assistant shows him a Penthouse magazine, with a brief flash of images from the magazine on the scene. Adultery is implied but not shown. There is some anti-God talk, primarily in the form of denials and denunciations from the physicist. In at least one scene, this probably rises to the level of mockery. (Steven calls God a “celestial dictator.”) The film is geared towards adults in its subject matter but is not particularly explicit in its stylization.