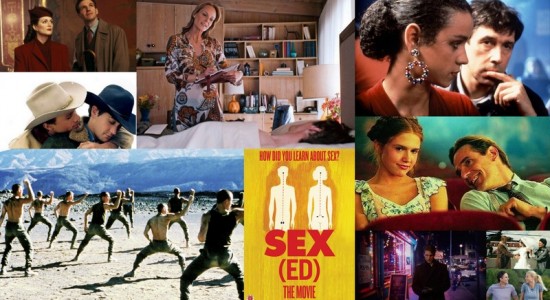

10 Movies about Sex that are Better Choices than 50 Shades of Grey

Ultimately indifference is a better critique of a movie than outrage. Sex is a legitimate subject for art, and there have been countless films that have explored human sexuality. Here then are some suggestions for films that might be better uses of your time than would be watching the one that opens this weekend. I tried to select films that were in some meaningful way about sex and not just ones that incidentally depicted sex.

10) Sex(Ed) the Move –Brenda Goodman

This crisp seventy-seven minute documentary chronicles the ways we have tried to educate ourselves about sex. Watching a teacher interact with elementary students after watching a sexual education video is instructive. The great, sad irony of our culture is that we are both saturated with sex and yet still intensely squeamish when talking about it. Is that squeamishness a function of innate modesty or the byproduct of natural curiosity trying to overcome shame? Watch the kids; they are interesting. As Christians we like to think attitudes towards sex are eternal–or at least shaped by eternal, unchanging truths. But if this documentary does nothing else, it prompts you to think about how you learned about sex and how your classroom–be it literal, domestic, or illicit–had a huge impact on the ideas you developed it in it. The film does go to Fox News as the easy (lazy) articulation of the straw-man opposition, but ultimately I liked it more as an historical document than a polemical argument. See also: And the Band Played On.

This crisp seventy-seven minute documentary chronicles the ways we have tried to educate ourselves about sex. Watching a teacher interact with elementary students after watching a sexual education video is instructive. The great, sad irony of our culture is that we are both saturated with sex and yet still intensely squeamish when talking about it. Is that squeamishness a function of innate modesty or the byproduct of natural curiosity trying to overcome shame? Watch the kids; they are interesting. As Christians we like to think attitudes towards sex are eternal–or at least shaped by eternal, unchanging truths. But if this documentary does nothing else, it prompts you to think about how you learned about sex and how your classroom–be it literal, domestic, or illicit–had a huge impact on the ideas you developed it in it. The film does go to Fox News as the easy (lazy) articulation of the straw-man opposition, but ultimately I liked it more as an historical document than a polemical argument. See also: And the Band Played On.

9) Beau Travail — Claire Denis

Of all the films on this list, this is the one I can most anticipate someone saying that it’s not “about” sex. At least not centrally. Denis transplants Herman Melville’s Billy Budd into a French Foreign Legion setting. Maybe it’s the fact that I know Billy Budd. A central theme in that novella is the inscrutable nature of Claggart’s hatred for Billy, one that many readers have attributed to repressed homoerotic desire. Beau Travail is a film some may find difficult for its indifferent commitment to narrative, a plotlessness that makes its casual but intense scrutiny of the male body all the more noticeable and arresting. The film concludes with an ecstatic solo dance from star Denis Lavant that has been interpreted every which way. Whether it symbolizes something sexual in the character or not is certainly open to dispute. That it is a powerful reminder that we are flesh as well as spirit is not.

Of all the films on this list, this is the one I can most anticipate someone saying that it’s not “about” sex. At least not centrally. Denis transplants Herman Melville’s Billy Budd into a French Foreign Legion setting. Maybe it’s the fact that I know Billy Budd. A central theme in that novella is the inscrutable nature of Claggart’s hatred for Billy, one that many readers have attributed to repressed homoerotic desire. Beau Travail is a film some may find difficult for its indifferent commitment to narrative, a plotlessness that makes its casual but intense scrutiny of the male body all the more noticeable and arresting. The film concludes with an ecstatic solo dance from star Denis Lavant that has been interpreted every which way. Whether it symbolizes something sexual in the character or not is certainly open to dispute. That it is a powerful reminder that we are flesh as well as spirit is not.

8) Brokeback Mountain — Ang Lee

Here again I anticipate fans and critics alike complaining that the movie is about something other than sex, or, at least, more than sex. Some may say that its about love. But isn’t the main reason the film was so disturbing, both to some straight audiences and to the characters in it, was that it acknowledges that love seeks to express itself physically? Brokeback‘s threat to straight viewers (at least to the extent I understand it) has less to do with its homosexual content than its rejection of the cultural notion that Platonic love is a higher, more noble form of love than erotic love. It is the nature of love to seek to express itself fully; if we suggest it cannot do so, we on some level deny that it is love. At the very least we consign that “love”–consciously or not–to a lower status. I haven’t revisited the film lately, but I recall the sexual contact as being less explicit than I anticipated by today’s standards. So the film also contributes a comment about our double standards. We absorb a lot more heterosexual imagery in mass media than we realize, I think, and we often do so without batting an eye. See also: The Servant.

Here again I anticipate fans and critics alike complaining that the movie is about something other than sex, or, at least, more than sex. Some may say that its about love. But isn’t the main reason the film was so disturbing, both to some straight audiences and to the characters in it, was that it acknowledges that love seeks to express itself physically? Brokeback‘s threat to straight viewers (at least to the extent I understand it) has less to do with its homosexual content than its rejection of the cultural notion that Platonic love is a higher, more noble form of love than erotic love. It is the nature of love to seek to express itself fully; if we suggest it cannot do so, we on some level deny that it is love. At the very least we consign that “love”–consciously or not–to a lower status. I haven’t revisited the film lately, but I recall the sexual contact as being less explicit than I anticipated by today’s standards. So the film also contributes a comment about our double standards. We absorb a lot more heterosexual imagery in mass media than we realize, I think, and we often do so without batting an eye. See also: The Servant.

7) Thanks for Sharing — Stuart Blumberg

I had some issues when I saw Thanks for Sharing at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival. I still do. There’s more stress on the “addiction” part of sex addiction than on the “sex” par of it, and I do think the “B” story humor undercuts the moral seriousness of the movie more than it helps. But you know what? I’m willing to forgive a lot of the film’s deficiencies because of two scenes. The cultural work of Mark Ruffalo’s character steering his girlfriend (played by the never sexier Gwyneth Paltrow) away from a lap dance because its taking him to a “dark place,” is really important, I think. On the surface it may be misunderstood as simply drawing a line at certain practices, but I ultimately think it’s an admission that past actions–good and bad–affect our present state. In that way, it’s one of the more sobering warnings one will get in a sex film. One of the costs of casual, premature, or illicit sex is the potential loss of future (greater) pleasures. Also when Ruffalo’s and Paltrow’s characters argue that her “health nut” obsession is as much an addiction as his sex obsession, the film borders on a keen, necessary observation: a healthy attitude and understanding of sex is more than just the prohibition of certain practices. It can only exist where we have a correct, comprehensive theology of the body. Want to know why there have always been such intimate associations between lust and gluttony? Both are physical pleasures running amok.

I had some issues when I saw Thanks for Sharing at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival. I still do. There’s more stress on the “addiction” part of sex addiction than on the “sex” par of it, and I do think the “B” story humor undercuts the moral seriousness of the movie more than it helps. But you know what? I’m willing to forgive a lot of the film’s deficiencies because of two scenes. The cultural work of Mark Ruffalo’s character steering his girlfriend (played by the never sexier Gwyneth Paltrow) away from a lap dance because its taking him to a “dark place,” is really important, I think. On the surface it may be misunderstood as simply drawing a line at certain practices, but I ultimately think it’s an admission that past actions–good and bad–affect our present state. In that way, it’s one of the more sobering warnings one will get in a sex film. One of the costs of casual, premature, or illicit sex is the potential loss of future (greater) pleasures. Also when Ruffalo’s and Paltrow’s characters argue that her “health nut” obsession is as much an addiction as his sex obsession, the film borders on a keen, necessary observation: a healthy attitude and understanding of sex is more than just the prohibition of certain practices. It can only exist where we have a correct, comprehensive theology of the body. Want to know why there have always been such intimate associations between lust and gluttony? Both are physical pleasures running amok.

6) The Sessions — Ben Lewin

Again, this is not a perfect movie. Todd Truffin and I podcast about this film in 2012, but we focused on the representation of the priest (played by William H. Macy). One of those “inspired by a true story” films, The Sessions is about a man in an iron lung who hires a sex surrogate (Helen Hunt in an Oscar-nominated role) to help him lose his virginity. It is evident early on, though, that the man wants something more than mercantile sex. His surrogate can’t give him those things; she can only really do what she does if she maintains strict boundaries about the number of sessions they have and the nature of their relationship. On one level, the way The Sessions plays out its conflicts is fairly conventional. Still, I thought it was important to have on this list because 50 Shades of Grey is (marginally) about bondage and control. The ways in which sex gets interwoven with issues of power, dominance, and control, isn’t exactly articulated in The Sessions, but those issues are unquestionably present. Because of the man’s physical incapacity, the woman is in complete control of the sexual elements of their relationship. What the film is honest about is that no amount of physical dominance or control ensures psychological or emotional control as well. See also: She’s Lost Control.

Again, this is not a perfect movie. Todd Truffin and I podcast about this film in 2012, but we focused on the representation of the priest (played by William H. Macy). One of those “inspired by a true story” films, The Sessions is about a man in an iron lung who hires a sex surrogate (Helen Hunt in an Oscar-nominated role) to help him lose his virginity. It is evident early on, though, that the man wants something more than mercantile sex. His surrogate can’t give him those things; she can only really do what she does if she maintains strict boundaries about the number of sessions they have and the nature of their relationship. On one level, the way The Sessions plays out its conflicts is fairly conventional. Still, I thought it was important to have on this list because 50 Shades of Grey is (marginally) about bondage and control. The ways in which sex gets interwoven with issues of power, dominance, and control, isn’t exactly articulated in The Sessions, but those issues are unquestionably present. Because of the man’s physical incapacity, the woman is in complete control of the sexual elements of their relationship. What the film is honest about is that no amount of physical dominance or control ensures psychological or emotional control as well. See also: She’s Lost Control.

5) Breaking the Waves — Lars von Trier

The cresting of 50 Shades of Grey as a cultural phenomenon will undoubtedly send some critics back to von Trier’s Nymphomaniac as a safer-for-your-reputation-to-recommend-because-it-is-by-a-serious-director alternative. I found von Trier’s latest to be repetitive and somewhat facile. It seemed to strive too hard to recapture the genuinely shocking impact of his earlier masterpiece, Breaking the Waves. Not for the faint of heart–what von Trier film is?–Waves tracks the downward sexual spiral of a newlywed wife (Emily Watson) who (maybe) thinks her idle prayer brought calamity on her husband. When his injuries make him unable to perform sexually, he suggests the next best thing would be for her to sleep with other men so that he can at least experience sex vicariously. Like most of the better films about sex, this one touches on additional themes. How the wife’s church community rejects her can be read as a glib condemnation of the church’s hypocrisy. Maybe it is. I prefer to think it is about how ill equipped the church is (how ill equipped we all are, really) to handle problems we don’t understand. I’ve never quite gotten on board with the interpretation of Watson’s character as a Romantic happy idiot; her sexual frustrations and brokenness seem to predate her husband’s accident. But in that, too, the film is perceptive. In subcultures that deal with sex simply by telling people to wait until marriage, people often enter into marriage ill equipped to handle the transition into fully realized sexual beings. (I’m not arguing that abstinence before marriage is bad advice, just that it is insufficient advice.)

The cresting of 50 Shades of Grey as a cultural phenomenon will undoubtedly send some critics back to von Trier’s Nymphomaniac as a safer-for-your-reputation-to-recommend-because-it-is-by-a-serious-director alternative. I found von Trier’s latest to be repetitive and somewhat facile. It seemed to strive too hard to recapture the genuinely shocking impact of his earlier masterpiece, Breaking the Waves. Not for the faint of heart–what von Trier film is?–Waves tracks the downward sexual spiral of a newlywed wife (Emily Watson) who (maybe) thinks her idle prayer brought calamity on her husband. When his injuries make him unable to perform sexually, he suggests the next best thing would be for her to sleep with other men so that he can at least experience sex vicariously. Like most of the better films about sex, this one touches on additional themes. How the wife’s church community rejects her can be read as a glib condemnation of the church’s hypocrisy. Maybe it is. I prefer to think it is about how ill equipped the church is (how ill equipped we all are, really) to handle problems we don’t understand. I’ve never quite gotten on board with the interpretation of Watson’s character as a Romantic happy idiot; her sexual frustrations and brokenness seem to predate her husband’s accident. But in that, too, the film is perceptive. In subcultures that deal with sex simply by telling people to wait until marriage, people often enter into marriage ill equipped to handle the transition into fully realized sexual beings. (I’m not arguing that abstinence before marriage is bad advice, just that it is insufficient advice.)

4) Lolita — Adrian Lyne

Settle down Kubrick fans, I’ll get to Stanley in a second. The truth is that no film could probably do justice to Vladimir Nabokov’s hypnotic, unblinking portrait of a soul in torment. If I prefer Adrian Lyne’s attempt it is only because Jeremy Irons does such a good job of reading Nabokov on the audio book that I tend to think of him as Humbert Humbert. And if you can only get one aspect of the story spot-on, capturing the essence of the confessional but unrepentant pedophile is probably the one you want to choose. That’s not to say other aspects are horrible. The central problem any adaptation faces is that it must pick an actress to play Delores who is old enough to defend the film’s makers from themselves abusing a minor and yet not so old that the film plays out as a May-December romance rather than as the rape of a child. It’s an acting cliche these days that nobody, not even Hannibal Lecter, thinks of himself as a monster. Ultimately, I don’t think Humbert does either. But he sure knows the world will think him one, and one of the many, many insights about sex the story offers is that in this arena, what the world thinks of you may actually be more important than what you are. There are a lot of really intelligent critiques of Lolita. Some complain that Dolores gets symbolically annihilated, that we never see her as a real person, only as the object of Humbert’s obsession. That’s only really true if you fall prey to Humbert’s hypnotic prose. The scariest thing about Lolita is not that predators exist. You can turn on the evening news any day of the week and be reminded of that fact. The scariest thing about Lolita is just how much power words have, even to the point of making us look past what is right under our nose. Even to the point of making us doubt that those sounds we hear are really the muffled cries of little girls. See also: Girl Model, Hardcore.

Settle down Kubrick fans, I’ll get to Stanley in a second. The truth is that no film could probably do justice to Vladimir Nabokov’s hypnotic, unblinking portrait of a soul in torment. If I prefer Adrian Lyne’s attempt it is only because Jeremy Irons does such a good job of reading Nabokov on the audio book that I tend to think of him as Humbert Humbert. And if you can only get one aspect of the story spot-on, capturing the essence of the confessional but unrepentant pedophile is probably the one you want to choose. That’s not to say other aspects are horrible. The central problem any adaptation faces is that it must pick an actress to play Delores who is old enough to defend the film’s makers from themselves abusing a minor and yet not so old that the film plays out as a May-December romance rather than as the rape of a child. It’s an acting cliche these days that nobody, not even Hannibal Lecter, thinks of himself as a monster. Ultimately, I don’t think Humbert does either. But he sure knows the world will think him one, and one of the many, many insights about sex the story offers is that in this arena, what the world thinks of you may actually be more important than what you are. There are a lot of really intelligent critiques of Lolita. Some complain that Dolores gets symbolically annihilated, that we never see her as a real person, only as the object of Humbert’s obsession. That’s only really true if you fall prey to Humbert’s hypnotic prose. The scariest thing about Lolita is not that predators exist. You can turn on the evening news any day of the week and be reminded of that fact. The scariest thing about Lolita is just how much power words have, even to the point of making us look past what is right under our nose. Even to the point of making us doubt that those sounds we hear are really the muffled cries of little girls. See also: Girl Model, Hardcore.

3) The Crying Game — Neal Jordan

Has enough time past that I can talk about the film without giving away the twist? Consider this your spoiler alert, since I really can’t talk about the film in this context without talking about the twist. The first act of the film is a political thriller, with Fergus (Stephen Rea), an IRA terrorist/soldier assigned to guard Jody (Forest Whitaker in what I think is his best performance), a kidnapped British solider. When Jody is killed, we think that is the twist, so when Fergus looks up Jody’s “woman,” Dil (Jaye Davidson), we are perhaps distracted enough to not notice her Adam’s apple until she reveals other, harder to ignore, parts of her anatomy. If one were so inclined, one could knock The Crying Game for its use of Dil as a straight guy’s urban legend nightmare. I’m not so inclined. The film gets most interesting to me after the big reveal. Fergus, as repulsed as he is, can’t turn his back on Dil, and I would argue that part of the reason why is that sex binds you to another person regardless of whether you understood what you were doing when you did it. The film can’t quite figure out what to do with its set up or how to develop its themes. The end, like the beginning, retreats to the safety of its genre frame’s conventions. That’s okay, though, because that middle is so subversive, so emotionally complex, that its ripples carry right through to the end. For some of us–straight, middle-class American males of a certain age, Dil was the first transgender character we met at the movies…and I am grateful that first portrait was of a person who was presented as a fully realized human being rather than a comedic target (Rocky Horror Picture Show) or psychopathic serial killer (The Silence of the Lambs).

Has enough time past that I can talk about the film without giving away the twist? Consider this your spoiler alert, since I really can’t talk about the film in this context without talking about the twist. The first act of the film is a political thriller, with Fergus (Stephen Rea), an IRA terrorist/soldier assigned to guard Jody (Forest Whitaker in what I think is his best performance), a kidnapped British solider. When Jody is killed, we think that is the twist, so when Fergus looks up Jody’s “woman,” Dil (Jaye Davidson), we are perhaps distracted enough to not notice her Adam’s apple until she reveals other, harder to ignore, parts of her anatomy. If one were so inclined, one could knock The Crying Game for its use of Dil as a straight guy’s urban legend nightmare. I’m not so inclined. The film gets most interesting to me after the big reveal. Fergus, as repulsed as he is, can’t turn his back on Dil, and I would argue that part of the reason why is that sex binds you to another person regardless of whether you understood what you were doing when you did it. The film can’t quite figure out what to do with its set up or how to develop its themes. The end, like the beginning, retreats to the safety of its genre frame’s conventions. That’s okay, though, because that middle is so subversive, so emotionally complex, that its ripples carry right through to the end. For some of us–straight, middle-class American males of a certain age, Dil was the first transgender character we met at the movies…and I am grateful that first portrait was of a person who was presented as a fully realized human being rather than a comedic target (Rocky Horror Picture Show) or psychopathic serial killer (The Silence of the Lambs).

2) Eyes Wide Shut — Stanley Kubrick

I’ve written a lengthy review of Eyes Wide Shut which I re-posted at this blog, so rather than trying to condense my comments to a paragraph, I will link to my full analysis. For now I’ll just remind readers with more curated sensibilities and who might have been living in a cave for the last two decades that there is a lot of sex and nudity in the film. None of it is erotic. Not the ritualized orgy that Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) attends nor the routine sex he has with his wife, Alice (Nicole Kidman), during which she and he sense he is not really present. The most erotic sex in the film is actually the sex Bill sees in his head after Alice confesses a lustful fascination with a naval officer. It seems to me that a major theme in the film is the increasingly broadening gap between our unrealistic and unrealized fantasies of what great sex should be and the more mundane experiences of what sex is–or becomes–for most people. It’s also worth reiterating a conclusion I come to in my full review: for a film as explicit as it is in depicting sex, Eyes Wide Shut is actually fairly conventional in its attitudes towards the subject. Bill (definitely) and Alice (maybe) are not so much acting out repressed desires as they are trying to find their way in a world that doesn’t conform to their expectations or internalized teachings regarding what sex is. We’re not exactly rooting for Bill to act out sexually–at least I wasn’t–but some of us might end up hoping that the couple can integrate into their own relationship the things that Bill as yet doesn’t even know how to articulate, much less ask for. Based on Alice’s last line, there is reason to hope they might.

I’ve written a lengthy review of Eyes Wide Shut which I re-posted at this blog, so rather than trying to condense my comments to a paragraph, I will link to my full analysis. For now I’ll just remind readers with more curated sensibilities and who might have been living in a cave for the last two decades that there is a lot of sex and nudity in the film. None of it is erotic. Not the ritualized orgy that Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) attends nor the routine sex he has with his wife, Alice (Nicole Kidman), during which she and he sense he is not really present. The most erotic sex in the film is actually the sex Bill sees in his head after Alice confesses a lustful fascination with a naval officer. It seems to me that a major theme in the film is the increasingly broadening gap between our unrealistic and unrealized fantasies of what great sex should be and the more mundane experiences of what sex is–or becomes–for most people. It’s also worth reiterating a conclusion I come to in my full review: for a film as explicit as it is in depicting sex, Eyes Wide Shut is actually fairly conventional in its attitudes towards the subject. Bill (definitely) and Alice (maybe) are not so much acting out repressed desires as they are trying to find their way in a world that doesn’t conform to their expectations or internalized teachings regarding what sex is. We’re not exactly rooting for Bill to act out sexually–at least I wasn’t–but some of us might end up hoping that the couple can integrate into their own relationship the things that Bill as yet doesn’t even know how to articulate, much less ask for. Based on Alice’s last line, there is reason to hope they might.

1) The End of the Affair — Neal Jordan

Neal Jordan’s pitch-perfect adaptation of Graham Greene’s veeeeery loosely autobiographically-inspired novel is one of those rare films that improves a good book. (I would argue that most movies that are better than the books they adapt–Jaws, The Godfather–are so because the books were pretty mediocre to start with.) The story follows Bendrix (Ralph Fiennes), the Greene avatar who hires a private detective to spy on his former mistress, Sarah (Julianne Moore). She broke off their affair without explanation, and while Bendrix thought he was over her, rumor that she has taken a new lover spurs his jealousy. What the investigation reveals is the true reason for her refusing to see him. I consider Greene one of the great novelists of the twentieth century, but if I have a qualm about his prose, its that he often uses his considerable Jesuit-honed intellect as a shield. When the film hones and prunes the plot, it usually does so to reduce some of the speechifying between the we-think-he-doth-protest-too-much-Atheist author and the representatives of the Christian faith. Of course, the biggest, most unanswerable evidence of God’s existence is Sarah herself. While Bendrix has no trouble throwing away the soul he doesn’t believe he has, he perhaps intuits that to get Sarah to repudiate her soul would be to fundamentally alter the object of his love. Like so many films on this list, The End of the Affair is about more than sex, but it is more about sex than some viewers might realize. I say that because it is not just about whether or not characters will have sex as it is about what happens when they do. And by that, I don’t just mean what the consequences are of having sex (though that is part of it) but also what the metaphysical meaning of sexual union is. If I close my eyes, no matter how long it has been since I last saw the film, I can still hear Maurice lashing out with his famous, “I hate you God…I hate you as though you existed.” It’s a thin line between love and hate, and nothing quite blurs it or carries us over it like sex. Of course we can’t have sex with God, but for all the things Maurice is wrong about, there is a profound truth that he is more in touch with than are many Christians. You can’t love what doesn’t exist, and it’s near impossible to love an abstraction. For a materialist, that means sex is the highest form of love, because a person only exists as a body. Sarah’s insistence that she can love apart from sex is a threat not just to Bendrix’s pleasure, but to his whole world view.

Neal Jordan’s pitch-perfect adaptation of Graham Greene’s veeeeery loosely autobiographically-inspired novel is one of those rare films that improves a good book. (I would argue that most movies that are better than the books they adapt–Jaws, The Godfather–are so because the books were pretty mediocre to start with.) The story follows Bendrix (Ralph Fiennes), the Greene avatar who hires a private detective to spy on his former mistress, Sarah (Julianne Moore). She broke off their affair without explanation, and while Bendrix thought he was over her, rumor that she has taken a new lover spurs his jealousy. What the investigation reveals is the true reason for her refusing to see him. I consider Greene one of the great novelists of the twentieth century, but if I have a qualm about his prose, its that he often uses his considerable Jesuit-honed intellect as a shield. When the film hones and prunes the plot, it usually does so to reduce some of the speechifying between the we-think-he-doth-protest-too-much-Atheist author and the representatives of the Christian faith. Of course, the biggest, most unanswerable evidence of God’s existence is Sarah herself. While Bendrix has no trouble throwing away the soul he doesn’t believe he has, he perhaps intuits that to get Sarah to repudiate her soul would be to fundamentally alter the object of his love. Like so many films on this list, The End of the Affair is about more than sex, but it is more about sex than some viewers might realize. I say that because it is not just about whether or not characters will have sex as it is about what happens when they do. And by that, I don’t just mean what the consequences are of having sex (though that is part of it) but also what the metaphysical meaning of sexual union is. If I close my eyes, no matter how long it has been since I last saw the film, I can still hear Maurice lashing out with his famous, “I hate you God…I hate you as though you existed.” It’s a thin line between love and hate, and nothing quite blurs it or carries us over it like sex. Of course we can’t have sex with God, but for all the things Maurice is wrong about, there is a profound truth that he is more in touch with than are many Christians. You can’t love what doesn’t exist, and it’s near impossible to love an abstraction. For a materialist, that means sex is the highest form of love, because a person only exists as a body. Sarah’s insistence that she can love apart from sex is a threat not just to Bendrix’s pleasure, but to his whole world view.

— Love doesn’t end, just because we don’t see each other.

— Doesn’t it?

— People go on loving God, don’t they? All their lives. Without seeing Him.

— That’s not my kind of love.

— Maybe there is no other kind.

That’s about as Christian a pronouncement as you are likely to hear in a mainstream, studio-distributed, American film, isn’t it?

Like 1More Film Blog on Facebook:

Although I haven’t seen 50 Shades, I would think both Shame and Don Jon could be on this list.

Don’t recall too much about Shame. I wasn’t a huge Don Jon fan (http://www.patheos.com/blogs/1morefilmblog/don-jon-gordon-levitt-2013/), though I agree it is a more serious film than 50 Shades, which is something. Might lump it in with Thanks for Sharing since it’s a bit more about addiction (pornography) than sex, imo. Thank you for the feedback.

You left out Last Tango in Paris. It must beat at least one of the above ten?

Frank, I concede that Tango is a better choice than 50 Shades and a better movie overall than some on this list. I don’t mean to suggest the list is comprehensive. I found Tango a bit labored, but I saw it many years ago, and I suspect the impact of some of these films is as much about when one sees them than about the overall quality of the film itself.

Thanks for the reply, Ken. I know that any best-of list has to split hairs…mainly wanted to call it to your readers’ attention. I concede that I didn’t specify which one in your list that it beats is that I haven’t seen any of them. 🙂