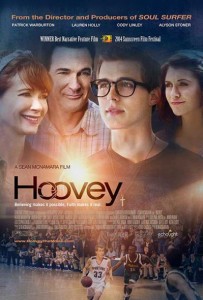

Hoovey (McNamara, 2015)

Hoovey (★★) is not a particularly good film, but it is a safe film.

It is the sort of film about which a youth pastor or sleep-over-host parent can skim a capsule summary and know exactly what he or she is getting. If it never surprises, neither does it provoke. For those who prefer their entertainment with a Christian flavor and an easy to discern moral lesson, it suffices.

The title refers to the nickname of high-school basketball star Eric Elliott (Cody Linley), whose idealized, Midwest family looks and talks like it came to life from a P. Buckley Moss painting. Mom (Lauren Holly) defiantly bites into a carby breakfast in front of her astonished daughter, Jen (Alyson Stoner), shrugging that “swimsuit season is over.” Dad (Patrick Warburton) manages to take breaks from yard work, farming, and fire-and-rescue volunteering to play one-on-one with his son. The Elliotts are the sort of family who are so loving that even the father-son basketball trash-talking is tinged with endearments and affirmations.

We get one scene with the generically inspiring tough-but-loving coach to set up Hoovey’s love of the game–and the presence of a sullen African-American prima donna threatening to ruin team chemistry–before our hero starts having blurred vision and headaches as portentous as Camille’s first cough. It may be coincidental or even biographical that every time Eric’s health is in serious jeopardy it is an African-American who delivers the hard foul on the court or threatens physical violence off of it; either way, the film’s racial politics are one of many areas where one suspects the it is somewhat oblivious to how it might be perceived by those not already predisposed to adore it.

Eric’s got a brain tumor, and the middle section of the film could have swapped second reels with Heaven is For Real and I’m not sure anyone would have noticed. We get a race against time to the hospital (complete with a voice-over explicating the meaning of the sudden appearance of help immediately after Jeff’s prayer), and grim prognostications of financial ruin due to hospital bills. Nothing so serious that will keep dad from getting his daughter a car, though, or that can’t be solved by mowing a couple of lawns on the weekend. The Elliotts are a plucky, resilient bunch who let their light shine by facing life’s challenges with can-do gumption and unswerving faith in God’s goodness.

Eventually, it’s time for Hoovey to get back on the court, because what good is a sports film if you can’t have a climactic big-game? One indication that the film is uncertain regarding what it’s about: it spends twenty of its eighty-plus minutes giving us a back-and-forth chronicle of a game that–by its own admission–is essentially meaningless. The only thing really at stake in the game is Hoovey’s life, and if that seems like a strange sentence to read, well…

Still, we get the obligatory shot of the clock winding down to twenty-three seconds, followed by a cut to Hoovey who dribbles once or twice and fires a desperation shot. At this point, the clock over the basket reads “35.” (Perhaps Eric is also one of the kids in Project Almanac?) The ball mysteriously stays in the air for 34 seconds, though, because the clock is reading 00:01 as Eric’s rainbow descends.) Eric is fouled, of course. By an African-American player, of course. Banging his head in just the right spot, of course. I don’t want to be accused of spoilers, but if I told you at this point that the ball clanks harmlessly off the rim giving the other team the victory, that Eric goes into cardiac arrest and dies, and that his Christian parents eventually divorce over arguments regarding who thought it was a good idea to go against their son’s brain-surgeon’s advice because they’ve prayed about it and are convinced all things work for the good, would you believe me?

Until Christian films have better writing, their success will most likely be limited to their ability to appeal those who care less about the quality of the production than they do about the orthodoxy of its themes. They will also be largely dependent on star-talent to elevate the material. Warburton is so congenial that he carries large portions of the film, and his scenes with Stoner actually made me wish for a subtler, smarter movie that was focused on Jen rather than Eric. It’s worth noting, for example, that the Elliotts justify letting Eric play ball (at the risk of his life) because we are told (via another intrusive voice-over) that the alternative to letting your child pursue his passion is watching his soul shrivel and die. Yet when Jen wants to quit the track team and act in the school play, mom asks why she can’t do both and dad says maybe next year, since “we are not quitters.” If the film is aware of a parental double-standard, it certainly doesn’t show it. As is the case with Hoovey’s African-American teammate, the script occasionally brushes up against ambiguity or complexity at its fringes, but whenever it does so, it turns and flees faster than Joseph in the clutches of Potiphar’s wife.

Hoovey was the second film I’ve seen in as many years (with Heaven is for Real) that depicts Christian parents making a long, slow, retreat from the precipice of financial ruin, and I confess it bugs me that neither of those films seriously explored (or even more than broadly acknowledged) that part of that process was the marketing of its own story. I don’t begrudge the Elliotts their TED talks nor the Burpos their book, and (speaking as someone who has faced family tragedies) I wouldn’t go through what they endured for any amount of money. But I also wouldn’t begrudge any Christian viewer facing financial hardship hearing the advice to buckle down, work harder, and have confidence that God will provide at least a twinge of envy that their own flirtations with bankruptcy aren’t quite so soon-to-be-a-major-motion-picture sexy.

Marketing and reviewing Christian films has become a matter of identity politics, so I guess it behooves me to anticipate rebuttal and hasten to add evidence of my good-faith. Sean McNamara has made a Christian film I enjoyed; it was called Soul Surfer. I was also one of only four critics to give EchoLight’s The Christmas Candle a marginal “fresh” rating. So I don’t hate everything, much less everything Christian. I didn’t even hate this film. Not really. I just wanted it to be better.

Maybe not as good as Friday Night Lights–that would be a tall order–but at least as good as The White Shadow.

Is that asking too much? You tell me.