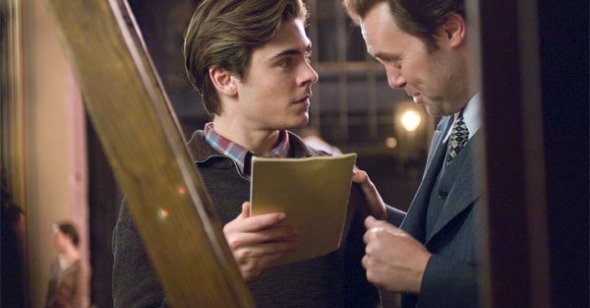

Me and Orson Welles (Linklater, 2008)

Most of my high school years were spent in and around the drama room at W.T. Woodson High School. Dramas in the fall (except, inexplicably my senior year when Mrs. B.—I could never quite forgive her—decided to do a second musical when I was ready to shoot for a dramatic lead), musicals in the spring, one-act play festival in between. The productions gave shape to the year, but it was the community that developed around the productions that gave shape to those years and what I actually remember more than stage business or particular performances. By my senior year, I was assisting in the introductory class while taking the advanced class. Over twenty-five years later, I still have the award given to one (and only one) graduating senior for outstanding contributions to the department. The friends I hung out with were almost all from the drama troupe. The girls I kissed (or wanted to kiss) were all in the drama troupe. My immersion and investment in that social group was such that being a writer, director, and actor was not something I considered my hobby or even my (eventual) vocation: it was my identity.

And somewhere in between May graduation and August enrollment at Mary Washington College (where the high school had performed the one-act festival and I had investigated the drama department before applying), I left that identity. I never enrolled in a drama class in college, never declared (nor even stated that I intended to declare) a drama major, never tried out for a production, never pursued it. To those who asked (and there were surprisingly few who did, excepting my parents), I shrugged and said neutral things. Not lies, exactly, but not the whole truth. The truth was I knew somewhere even in my eighteen year-old brain that the theater life was not the life I wanted. Because it was a life of narcissism and selfishness, of a kind of required self absorption and preoccupation. I should be careful and say that it wasn’t so much that way because of the people I shared it with, many of whom were and still are, good, generous, loving people whose friendship I treasured and (in some cases) continue to treasure. No, it was that way a bit by nature, because that’s what was required to be in it. It was the air you breathed, the food on which you sustained yourself. That life was, I realized even then, mostly a zero sum game. My gains were others’ losses. My disappointments were usually cause for celebration on the part of someone else. But it was also a life of exhilaration. The highs were genuine highs, born (for me, at least) out of accomplishments and possibilities and greater accomplishments rather than drugs and alcohol. The camaraderie of work was overlaid with the familiarity of school and almost (almost) passed for intimacy. There was nothing quite like being present when the great breakthrough happened. (All these years later, I still prefer David’s Clarence Darrow to Henry Fonda’s.) The moment when, in the midst of chaos, one gets a glimpse of the factors starting to come together, the feeling of reaching beyond what you have done before, and the thrill of succeeding to a greater degree than anyone thought possible were all serious highs. It was within such an environment where I first made meaningful choices about the sort of person I was and wanted to become.

It is to the credit of Me and Orson Welles that it managed to make me nostalgic for those days while also reminding me why I grew to move on from them. It is the best film I’ve seen about theater life (and make no mistake, it is about the theater and not the film community). Its pleasures and its insights into human relations are not dependant on a historic interest in Welles or the Mercury Theater, although it works on that level, too, I suppose.

Although the film is ultimately about Richard Samuels (Zac Effron), it is the representation of Welles (Christian McKay in one of those transcends-make-up-and-mimicry roles that usually garner statuette nominations for actors with major studio backing) that makes the film so emotionally resonant and ultimately satisfying. It is not just that Welles is a paradoxical combination of asshole and genius who forces the Faustian dilemma upon all who are intoxicated by the life he enables, though he certainly is. There have been plenty of films about audience surrogates who struggled with the question of what (and how much) to excuse from the rare genius who produced great art. (Amadeus is the archetypal example, but, really, name any great artist—literary, musical, visual, theatrical—and there is probably a biopic about him or her built around this conflict.) What strikes me as tonally different about this film is how self-aware (and intelligent) all those in Welles’s circle are. I would use the term “enablers” except that would imply a belief that the root behavior one is enabling is somehow wrong and that one’s support of it is something other than a matter of course. What is remarkable about the film’s construction is that as one person after another (Houseman, Cotten, Sonja) makes allowances for Welles’s increasingly despicable behavior. we (the audience) are both surprised at the lack of genuine moral indignation and surprised at our own surprise as we are constantly forced to think back through each incident of the film and wonder why we would or should expect any different.

That motif is most keenly felt in Samuels’s interactions with Sonja Jones, played in a remarkable performance by Claire Danes who must be ambiguous and transparent (no easy feat that), no different than anyone else and yet capable of making us feel as though she is. (I would have to watch the film again to really document this, but I certainly got the impression that Jones has a disproportionate number of face on or three-quarter close-ups, and that the quality I’ve called “transparency” has a lot to do with Danes’s ability and willingness to divest herself of actorly moments; it really is a remarkably mature and self-assured performance.) There’s a lot more I could say about the film that I haven’t really touched on. The script is remarkably clever without calling attention to itself and one could, I think, write a dissertation on the metafictive ways in which it instructs the audience in how to read it by having characters continually engage in acts of “reading” (or interpretation) themselves, from the opening “wouldn’t this be a good scene for a story?” meet cute between Samuels and Gretta Adler, to the “it was the bad luck part,” all the way through to the parroted lines of Wellesian praise that each recipient knows are simply recited lines but somehow manages to delude himself into feeling as though are personal messages sincerely constructed just for him. One could also talk about the film as a bildungsroman—I think it would make a very interesting comparison piece with Lone Scherfig’s An Education—or as a Richard Linklater auteur piece. (The combination of light, jazzy, surfaces and somber interior worlds makes me rethink Before Sunrise in terms of The Newton Boys rather than Slacker.) One could just focus on the triumph of the ensemble acting—Zac Effron, who’da thunk it? Is anyone firing on all cylinders right now more than Eddie Marsan? Ben freakin’ Chaplin! Get out of here. Heck, I even learned a few things about Julius Caesar. Anyway, it’s a marvelous film, that anyone who remembers the thrills of self-discovery can enjoy and that anyone who has ever been a part of a group—theater, work, sports, music–will appreciate all the more. Go see it.