Forgiving Dr. Mengele (Hercules, 2006)

I approached writing a review of this film with some trepidation. The act of reviewing carries with it a strain of judgment, and when reviewing a documentary it is hard not to feel as though one is judging the subject and not just the artists’ presentation of him or her. Which of us would dare judge Eva Moses Kor?

In a ceremony commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, Kor read a statement forgiving and offering amnesty to the Nazis that had tortured her, murdered members of her family, and attempted to exterminate her race. Kor describes forgiveness as an act of self-healing and self-liberation. In recollecting the event, she describes her act of forgiveness as prompting a “feeling of complete freedom” from the “burden” that carrying the pain of her experiences had placed upon her.

Jesus told his followers “If you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you” (Matthew 6:13). Because the topic of forgiveness is one that comprised such an important part of Jesus’s teaching and ministry, any film that deals with that topic intelligently and honestly is surely a worthy one for Christians to contemplate. Forgiving Dr. Mengele is both intelligent and honest, so I recommend it for Christian viewers. I’ve been around enough Christians, though, to know that some will bristle at Kor’s claim that forgiveness has “nothing to do with any religion” and that others will look with inherent suspicion upon someone from a faith tradition that does not recognize Jesus as the Messiah but nevertheless is able to enact some of his teaching at a deeper level than those who do.

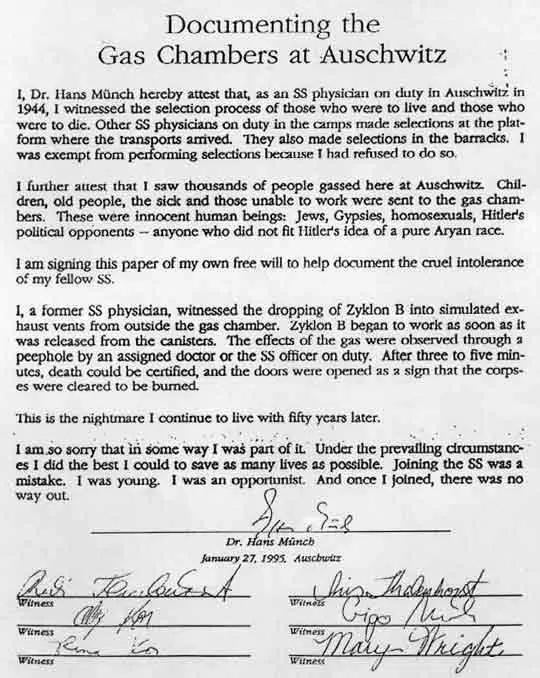

One truth about forgiveness that is amply illustrated in the film is that it is a process. The film does not present Kor as setting out to forgive Mengele. She first approaches another physician from the camp, Dr. Hans Munch, and asks him to read a testimonial refuting Holocaust deniers by attesting to what he witnessed. After learning that Munch is plagued by nightmares about his camp experiences, Kor gave Munch a letter of forgiveness. This intermediate step helped her to process and understand the dynamics and effects of forgiveness and prompted her to widen her circle of forgiveness to include those she did not initially think she could.

Another truth that is less explicit but still illustrated in the documentary is that forgiveness is rarely a one-time occurrence. Anger, resentment, and bitterness are fed by pain and fear, emotions that do not always evaporate when one faces them squarely. To the extent that Kor stresses the purpose of forgiveness as that of liberating the victim, it appears as though there is a need to reaffirm forgiveness in order to remain free of anger and bitterness .

Much of the film depicts Kor interacting with her detractors or questioners, particularly with their attempts to define the parameters within which forgiveness is either possible or morally justified. Most of us require some form of apology, restoration, or atonement on the part of the other party before we feel we are obligated to forgive. Kor, with her emphasis on the effects of forgiveness upon the victim, does not see apology or atonement as being necessary, a stance that angers many of her fellow survivors since forgiveness can be construed as applying to the unrepentant. To forgive those who have not repudiated their actions, Kor’s detractor’s argue, is to betray the oppressor’s other victims and to increase the likelihood that others may suffer the same fate.

Michael Berenbaum, identified in the film as a Holocaust scholar and author, offered one of the more dispassionate critique’s of Kor’s philosophy: “So the question is what you do…in order to get a certain sense of atonement or innocence. And for that I demand and I require gestures, acts, deeds of enormous significance. And I’m against, in every field, cheap grace. I understand where Eva’s coming from, but to my mind there’s something formulaic about it and therefore inadequate about it.” His critique is followed by an exchange between Kor and Jona Lake, another victim of Mengele’s experiments, to whom Kor acknowledges that forgiveness is an empowerment tool. These two scenes comprised one of the most complex passages in the film because they elicited so many mixed feelings. On what basis, I wondered, was Berenbaum able to decided what was demanded or required for atonement? His phrase “enormous significance” combined with the intimation that anything formulaic is somehow inadequate evidences the human tendency to trust our most volatile (and hence least trustworthy?) emotions when contemplating abstract or spiritual concepts such as justice, forgiveness, and atonement.

But just when I’m ready to accept that Kor’s understanding of forgiveness is more Christian than is her detractor’s, she will speak in the language of self-actualization, a language which suggests that God-like forgiveness may be an innate human potentiality rather than one that is enabled by God’s transformation of our innate fallen selishness. In addition, most Christians who hear the word “atonement” are going to believe that a “[deed] of enormous significance” is precisely what has made atonement or innocence possible–it’s just that this deed has been done by another, Christ, on behalf of the guilty party rather than by the guilty party himself. The absence of any room in this particular exchange for a consideration of Christ’s crucifixion as an atoning act makes Berenbaum’s intimation that Kor is practicing “cheap grace” simultaneously offensive and reasonable. It is offensive because it threatens to diminish the magnitude of Kor’s suffering; how are we to know whether the costs (emotional, spiritual, or social) of Kor’s forgiveness were cheap. It is reasonable because history demonstrates over and over again that the effects of great evil are seldom borne by a single victim. It may be true, even from a Christian perspective, that the effects of sin can be mitigated through human forgiveness alone–though even here I suspect that the Holy Spirit can and is involved in healing and empowering for good those outside the body of Christ who demonstrate Christ-like qualities–but it is untrue, from an orthodox Christian perspective, that the debt of sin can be forgiven by human action. So while I bristle at Berenbaum saying that it is he who requires the “gestures, acts, [or] deeds,” and while I think the use of the plural makes it clear that he is not thinking of Christ’s atonement, I still struggle with the fact that his insistence that some form of atonement is necessary makes it clear that his understanding of forgiveness will be probably be closer than Kor’s to what most Christian viewers believe.

Eva’s forgiveness of the Nazis may make it appear as though she is a proponent of universal forgiveness with no conditions, but the latter parts of the film show that she is clearly uncomfortable pursuing reconciliation with Palestinians. She explains this possible contradiction by saying that forgiveness cannot really happen “while people are fighting for their lives.” Later, she tells a group that her meeting with some Palestinians was “more than I could deal with.” I have seen some responses to the film that almost revel in this apparent contradiction as though it somehow invalidates or calls into question Kor’s previous actions. The scenes with the Palestinians actually made me respect and admire her even more. The fact that she did not respond in a rote, mechanical way, struck me as evidence that she was not being “formulaic” in her earlier response to the Nazis, that her words were not vain repetitions or magic incantations but sincere expressions of her internal feelings and beliefs. Also, despite the fact that the film shows her responding to the group of Palestinians by saying she does not want to hear their stories and does not think they can have a productive dialogue, she stays. In some ways, I found the act of listening when she could not yet offer peace or reconciliation to be as difficult and courageous as the act of forgiving.

The cruelest irony of the Palestinian interaction is that Kor’s understandable discomfort seems to render her oblivious to the fact that the Palestinians don’t appear to want forgiveness from her; they see themselves as victims of Israeli oppression who want her apology. To this observer, the most valuable message that Kor could have given the Palestinians was not “I forgive you as well” but “if I can free myself from the effects of hate and bitterness by forgiving, you can as well.” I’m not blaming Kor, though, for lack of reconciliation. Remember that her statement forgiving the Nazis came fifty years after the liberation of Auschwitz. Her statement that forgiveness “cannot really help while people are fighting for their lives” could just as easily be co-opted by the Palestinians (or by contemporary Jews who did not experience the Holocaust but have felt the effects of war and terrorism) as could her example. While the lack of a bridge between Jew and Palestinian unquestionably makes the second half of the documentary more pessimistic than the first, even the end is not without hope. Forgiveness does not end all conflicts nor does it prevent new ones from arising, but it can and does provide an example, one that–at the very least–contains a promise that freedom from the soul-destroying effects of anger and hate is a possibility.