2008 Top Ten

Yes, it is that time again. The deluge of end of year lists has begun, and I, as a self-proclaimed movie critic must contribute my own. This year I will again have two lists, my favorite 2008 films and my favorite “discoveries” (films from previous years that I screened for the first time in 2008). A lot of blogospheric ink is expended this time of year trying to distinguish between “Best of” lists and other, more personal lists. I suppose my own is closer to the latter than the former, though I fancy that I tend to favor personally films that are actually pretty good.

The creation, dissemination, and response to such lists have become marked by pettiness, pomposity, and preening—at least in the film blogosphere, which has become filled with these attitudes in general. I think the two standard tracks are to pick obscure films to validate how avant garde one is or two pick mainstream films to prove how one is not afraid to be labeled bourgeois by the effete and ineffectual critical consensus. There are other moves, I’m sure. And I’m well aware of how easy it is to build a review or a list around poking holes at others’ opinions. I would like to think I’m above such things, having arrived at a stage and point in my life where I have enough accomplishments that I don’t need everyone to love me or respect my opinions in order to feel good about myself and a point at which I don’t have the energy to engage in the relentless self-promotion and posturing that goes with marks the more solicitous forms of blogospheric film criticism.

As a result, I’ve grown more selective in the past few years, both in terms of what I see and what I write about. I don’t feel a need to write a review of The Incredible Hulk just because I saw it nor to take a side on debates about the merits of Slumdog Millionaire, which I liked more than the scoffers but less than zealots. If someone likes a film more than I did, even (especially?) another critic, what’s that to me? I guess I’d rather listen and hear why than immediately explain why he or she is wrong. What I find tedious is that they often spend more time explain why each other are wrong than just talking about what they liked about the films they liked.

Most of the films I’ve listed are ones I’ve already written about, and if I have, I try to note the link to the original review. I didn’t think 2008 was a particularly great year for films, but I know it was a pretty hairy year for me overall, so it could be that I didn’t see as many films as I normally would. I know a lot of the stuff that is being championed at the moment is stuff that underwhelmed me. Nevertheless, here are my annual favorites for anyone who wants to know.

10) Séraphine – Martin Provost

Link to my review at 1More Film Blog.

9) Three Monkeys — Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Link to my review at Looking Closer Journal.

I certainly appreciated Ceylan’s earlier films, Distant and Climates even if they were hard films to embrace. Three Monkeys is not what I would call a crowd pleaser, but it is a bit more accessible than the previous two films, and Ceylan’s visuals are always luscious. He can even make shades of gray look interesting.

8) The Visitor — Thomas McCarthy

The first thirty-five or forty minutes or so of Thomas McCarthy’s The Visitor is just sublime. It is measured. It reveals itself gradually. It is anchored by a sad and beautiful performance by Richard Jenkins. It’s leisurely. It doesn’t try too hard to be about anything. (Read more…)

7) Happy-Go-Lucky — Mike Leigh

Link to my review at Christian Spotlight on Entertainment.

I haven’t seen this film topping many (any?) end of year lists, but it sure feels like the film on all the lists that everyone is talking about. Of course, everyone is saying different things about it, which is what makes it so interesting.

My meta-pondering about the film has focused on whether or not that is a good thing. One school of thought (very New Critical that) is that I film should mean what it means, and if it is effective, most people ought to watch it and get mostly the same thing out of it. Another way to think about it, though, is that a film that gets people disagreeing gets people talking about it.

6) Forgetting Sarah Marshall — Nicholas Stoller

Link to my review at Christian Spotlight on Entertainment.

I’m somewhat tired of defending this film, so for the most part I’ll just post a link to my review. Perhaps, perhaps, comedy is it’s own justification. You either laugh or you don’t. And I found the puppet Dracula musical funny. I found Russell Brand very, very funny. I found Jason Segel alternately sad and funny. Mila Kunis puts the movie over the top with a wonderfully real and self-assured performance.

The end of the film will probably annoy some people, but it struck me as being honest and true. Rachel (Kunis) tells Peter (Segel) to go away, and he does. She tells him not to call, and he doesn’t. She has a conversation with one of her friends that ostensibly makes her see things differently, but really, she just gets tired of being alone, I think. In some ways, the end of the film reminds me of the end of John Sayles’s Honeydripper. You wonder how the characters are going to extricate themselves from a particular situation, and then the truth is revealed. And some people just choose to look past the truth. Do they look to a deeper truth? To what they want to be true? Or do they just decide that the truth means less to them than what they can have. I like that Rachel puts her foot down, but I think the film is honest about the consequences of trying to have and maintain expectations.

Do I think people will be watching this film in school twenty years from now? Probably not. (Unless there is a unit on the influence of Apatow or a retrospective on one of the actors.) But if you ask me what studio film I enjoyed the most last year, this is it.

5) At the Edge of the World — Dan Stone

Director Dan Stone commented in a phone interview that the transformation of the viewer provided the through arc for this documentary about Sea Shepherd and its attempts to foil Japanese whaling vessels in the Antarctic circle.

Again, most of what I want to say about this film has already been said in fuller review (this one at Looking Closer), so I won’t repeat most of it here. End of year lists are good at revisiting or rethinking one’s immediate response, and although I haven’t screened At the Edge of the World a second time, I do think it has withstood sustained conversation.

As a documentary, the film is informative without being too polemical. It has a point of view, and its makers have (I imagine) their sympathies. That said, the documentaries I like best are the ones that trust the audience enough to simply give it the story and let the viewers grapple with it on their own terms. In an age where docugandas seem to dominate the landscape, it is nice to see a film that is rich in ideas and circumspect in presentation.

4) Lorna’s Silence — Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne

The passing of Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni last year (as well as the announced retirement of Eric Rohmer) sparked, as these things often do, another round of the “who are the greatest living directors” debate.

For me, such questions about writers and directors don’t really have a right answer. I think there is a group of artists who fit in the elite category and one’s inclusion in it is more significant than any casuistic rankings within it.

On a common sense level, the test for inclusion in that group is two-fold. First, they are the artists that, when you hear they have a new book or film, you feel immediately feel the pleasure of anticipation. They are the artists that the pleasure of watching their films actually begins before you watch and after you finish. Second, they are the authors or directors where you would line up to see the film simply because their names are attached to it. (Read more.)

3) Wendy and Lucy — Kelly Reichardt

Great art doesn’t always have to have its origin in huge ideas or projects of great scope. Minute observation of everyday life will always turn over questions of great significance, because we are all faced with and live through such questions. Wendy and Lucy is about a girl and her dog. From that relationship–and what happens to it when Wendy’s car breaks down on her way to what she hopes will be an opportunity for a new job and new start in Alaska.

In my review of the film at Looking Closer, I proposed, tongue-in-cheek, that the film’s central question was whether or not people who can not afford a dog should refrain from owning a dog. From that central question ripple others: is society structured to create a poverty tax? what is the nature of justice? responsibility? love?

It is part of the film’s charm that it doesn’t assume the answer to any one of these questions is inherently more significant than the others.

Michelle Williams gives one of those live-the-role performances that are skewered in Tropic Thunder but garner Academy Awards more often than ridicule. From some quarters I’ve heard complaints that the film wears its liberal politics on its sleeve, but I disagree. It shows the situation and invites you to think what you might have done differently from Wendy, whether those choices would have made a difference, or whether the causes of Wendy’s downward spiral are as much environmental as personal.

2) Still Walking — Hirokazu Koreeda

Here’s the thing that’s constitutionally wrong with me–I still don’t get Yazujiro Ozu. Everyone at this year’s Toronto Film Festival kept comparing Koreeda’s newest film to Ozu’s works–other critics I spoke with, audience Q&A participants, even some printed reviews. In one of his sessions with the audience at Toronto, Koreeda suggested somewhat facetiously that his characters were too messy for an Ozu film and that they might be more at home in a film by Mikio Naruse.

Certainly the film’s premise, a close examination of a family struggling against the weight of social expecations, would make (and has made) fodder for an Ozu film, but for me that’s a bit like calling any examination of doubt Bergmanesque.

As I mentioned in my review of the film (at Looking Closer), Koreeda suggested he structured the film around objects. This means that rather than being filtered through any one character, the family’s dynamics are revealed organically and no one character’s experiences are given the impratur of idealization. Certainly, given Koreeda’s admitted inspiration for the film–his own mother’s passing–one would expect Ryota’s (the eldest sone, played by Hiroshi Abe) perspective to dominate the film. The film is neither an indictment nor a celebration of the parents, though. What is surprising–and delightful–about the film is how clear-eyed the portrait of the family is even when the setting for it is a situation that would normally invite excessive sentimentality. Bittersweet is one of the hardest tones to capture, perhaps because we are so cynical that we tend to assume instinctively that it is parody. Koreeda reminds us that emotions that we too often mock (because we find them embarassing or painful) are real and, often, beautiful.

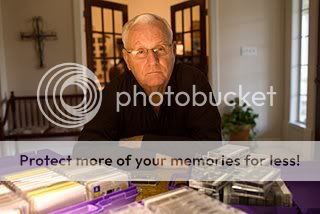

1) At the Death House Door — Peter Gilbert and Steve James

Link to my review at Looking Closer Journal.

I’m convinced in lists such as this one, that the top handful of films are usually somewhat interchangeable. Certainly any film on this list is one that I would recommend heartily, enjoy, and feel would reward multiple viewings. The differences, then, in order between the first few films has as much to do with the context in which one saw the film and one’s own pathology and viewing preferences.

After screening the film at the Full-Frame Documentary Film Festival in Durham, I wrote that the parts of the film focusing on the personal transformation of Carroll Pickett from prison chaplain to anti-death penalty activist was more engaging for me than the investigative report into the case of Carlos DeLuna. I still feel that way, and a part of me suspects that the bifurcated focus has made it easier for some to dismiss the film as merely and only a political polemic.

I have read some responses to film that dismiss as (and for) being too politically slanted. Maybe, but as with Hoop Dreams and Stevie, Gilbert and James are interested, first and foremost, in people. The film reflects the beliefs of the people in it.

Other responses have complained that the film is all set up and no pay off. We are told about the tapes onto which Pickett poured out his doubts and fears after each execution he has to witness, but we never hear them. We do hear Pickett, though, and I would argue that we know what is on them.

Pickett’s odyssey makes for an incredible story. One of the executions he had to preside over was of a man who killed a popular parishioner during a prison riot. Watching Pickett negotiate, even in memory, the complex of emotions that his job has forced him to reconcile, I was struck by how the film begins with the political and moves to the spiritual. Like Plato’s Republic, which cannot answer the question “What is Justice?” without describing the perfect society, At the Death House Door begins with a seemingly simple, direct question and shows how hopelessly complicated the simplest questions can be.