The Servant (Losey, 1963)

If you enter the terms “servant,” “losey,” and “creepy” into the Google search engine, you get approximately nine hundred hits. Not all of them, of course, are using the “c” word in connection to Joseph Losey’s 1963 film starring Dirk Bogarde and “introducing” James Fox, but enough of them are to make it clear that “creepy” is the adjective of choice for talking vaguely about Losey’s film without having to get too specific.

“Creepy” is one of those adjectives that names rather than describes, with at least one dictionary using the descriptors of “uneasiness” or “fear” to categorize the response to something which is analogous to what is felt when something creeps on one’s skin. Not all the uses of the word in association with Losey’s film must necessarily be read as coded indictments of the film’s subject matter as opposed to its presentation of it. There are some, though, I suspect who were more creeped out by the gay just-barely-sub subtext then by the notion of just any servant insinuating himself into the life and routine of just any employer.

Was the love that dared not speak its name so unpoken in 1963 that there were some who didn’t know what was creeping them out–who were simply disoriented by Losey’s mise-en-scène rather than led by it to draw some conclusions about the nature of Hugo’s and Tony’s odd relationship? Reconstructing the consciousness of an historical audience is a notoriously difficult proposition in both literary and film studies. What seems overbearingly obvious to us can be so because we have been conditioned to pick up on cues, symbols, and language through years of experience.

One interpretive problem of being on the other side of the celluloid closet opening up is that I can never be quite sure whether or not these older films are depicting gay characters who are hiding their identity from themselves or whether the director is using coded language and situations to get around censorship and society. There is a sort of brazen overtness in its visual insinuations that makes it hard to take the repression of the characters seriously no matter how much one reminds oneself that it might have once been a norm.

The Servant could very easily have been a silent film, so much does the staging of the characters point to their relations to one another more clearly than anything they say. Take this shot from key scene where Tony comes home from his date to find Hugo in bed. Sure, within the narrative there is flimsiest of pretexts that Tony’s shock comes from Hugo having told him that Vera is his “sister,” but the real shock is that he is in bed with any woman, not just this one:

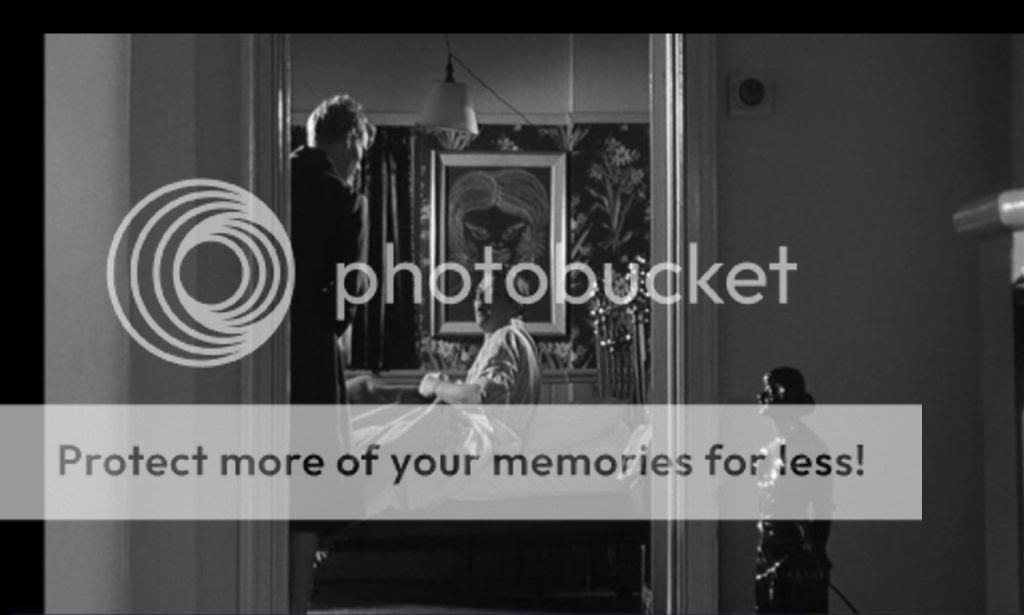

As we will see in subsequent screen grabs, Losey loves to use mirrors in this film, and so one is always seeing the reflection or shadow of bodies positioned between characters symbolically. This is, again, something that could have a non-homoerotic interpretation in the film’s narrative. Susan doesn’t like their privacy being invaded, such as in an early scene where the manservant “accidentally” walks in on the couple engaged in foreplay. But reading Susan’s animosity towards Hugo as resulting from her being merely irritated rather than threatened by him glosses over the fact that Susan has a hard time connecting with Tony even when they are not interrupted. There is something between them even when there is nothing there, and that tends to reinforce the interpretation that the shadow is the symbolic representation of what is there even when it is not. The male body is always between them, even when that body is not physically present.

As well as containing some obvious symbolism, the use of mirrors becomes a way of foregrounding what’s in the background. This visual motif suggests that the things that remain unspoken are nevertheless obvious to all but the most casual observers.

As several of the screen grabs above illustrate, Losey uses mise-en-scène in multiple ways, often combining visual motifs in shots. The shot immediately above, for instance, does not merely draw attention to the background, it also fragments the body, uses territorial space to suggest entrapment, and uses art work to convey (along with the mirrors) a feeling of surveillance which is almost overbearing. (This latter emphasis on being constantly watched certainly contributes, I think, to the film’s “creepiness,” since the fear of being watched or exposed is universal, even when one is not trying to hide a particular secret. Hardly a five minute stretch of the film goes by without some shot that could be used as a cover photo for Michel Foucault’s chapter on surveillance in Discipline and Punish.)

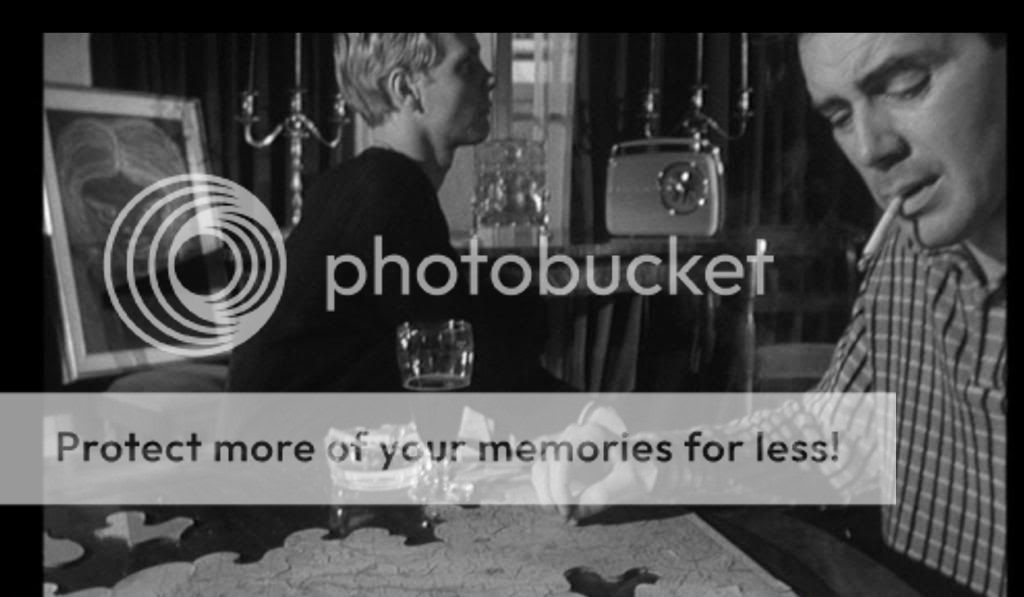

Paintings serve two purposes, then. One is to convey the feeling of surveillance, the other is to contrast the representation of the male and female form. The male figures reflected in the mirror in the shot above are traditional anatomy studies, presumably done by Tony, that demonstrate an attentiveness and attraction to the male form. Those pictures of women around the flat are exaggerated, caricaturized, and garish:

![The sketches to the left appear almost adolescently formed or conceived in comparison to the sketches of the male form..."]<](http://i457.photobucket.com/albums/qq299/kenmorefield/servant/servant7.jpg)

I mentioned in one of the first captions that Tony’s attempts to be intimate with Susan are thwarted by Barrett early in the film, but even when they are not interrupted, the mise-en-scène presents the acts of intimacy between a man and a woman as oddly (creepily?) unerotic. We get all measures of visual cues, from the fire and snow in the background, to the compartmentalization (and subsequent objectification) of the female body that intimacy is neither comfortable nor natural.

The previous shot also participates in the film’s fixation with feet. Feet and legs are erotic. Faces (particularly the female face) are more often blurred, hidden, or obliterated. (In one scene, Barrett symbolically places his hand over the window in a phone booth to cover up or blot out the woman’s face who is trying to get in.)

It doesn’t take an expert in visual iconography to suggest that the face is the seat of identity and that these attempts to compartmentalize the body are attempts to depersonalize desire. It’s worth pointing out, too, that unlike the objectification and fragmentation of the body that we might see in straight male pornography–that obliterates the face but focuses on the bust or female sexual organs–so many of the shots of the legs emphasize a certain degree of androgyny by not including the waist. The main visual message that I take away from these shots, however, is that the desirability of the female body is directly proportionate to the obliteration of her face, her identity, perhaps as a person but more particularly as a female. In one of the few paintings where the object of the painting looks away from rather than at the actors and thus becomes an object of contemplation (rather than a viewer), androgyny is a major theme, and the feet and legs are, one supposes, what draws Tony to so sensual image:

For my money, the two most creepy shots in the film deal with encounters between Tony and Vera. Several of the visual themes combine to give us depersonalized, deeroticized glimpses of sexual contact. The first incorporates the mirror theme the reinforce the idea of hidden-ness, while the hand coming around the corner perhaps symbolizes repression. (The emergent hand is iconic of that which is buried trying to come to the surface or that which is offscreen trying to push its may into our sight and consciousness.):

The other shot is disturbing for the way it fragments the female body and obliterates the male participant in the sexual encounter. Here the back of the chair shields us from seeing the act itself, and for once there are no mirrors to allow us see past the surface or around the frame to that which is hidden. The legs no longer work as synecdoche, because the face that has been trying to be obliterated emerges from behind the chair. We no longer have just a part, but neither is the body whole. It is disconnected. While we understand what is going on, we see no passion in the act, no love, not even pleasure:

The lack of wholeness and the desire for it is a major theme in the Robin Maugham novella on which The Servant is based. The short novel, written by the nephew of Somerset Maugham is a bit more of a monster story than is Losey’s film. Think of it as a cross between The Portrait of Dorian Gray and The Hand that Rocks The Cradle. Barrett is more openly and unsympathetically evil in the novel than the film, desiring Tony’s deterioration and destruction rather than simply causing it. While the film retains (loosely) the conventional structure of a domestic horror film–the gradual insinuation and enmeshment of a negative influence that disrupts and corrupts domestic tranquility (if not domestic happiness)–it actually comes off as less willing to posit that force as a malevolent one. The homoerotic attraction in the film is lure towards moral decay in the film, whereas it is the weakness that is exploited in the novella.

The film, in fact, does away with the narrator, Richard, who appears to be a Maugham surrogate and is Tony’s true love interest. Barrett acts more as a pimp than a scorned lover, using Vera and Tony’s own sense of shame at his sexual identity to gain control over him and pry him away from Richard. Basically, imagine the Wendy Craig character (Susan) as a guy from whose point of view the story is told, and you’ll get a pretty good sense of the novel.

By morphing Richard into Susan and making Barrett the gay interest, the film essentially makes Barrett tempt Tony with himself. While at first thought this would appear more likely to make him less sympathetic, it actually makes him more so–at least to modern readers. Barrett becomes a character with desires of his own (whatever you may think of them) rather than simply an agent of malevolence exploiting the (culturally branded) illicit desires of others.

Of course, changing Richard into Susan may have been the only way to get the film made in 1963. There’s subtext and then there’s, well, unspoken but implicit text. But in the change there lies an irony as well. While Barrett in the novel is the representative of the barriers that keep true love apart for no good reason, Barrett in the film is part of that love that can only express itself in sublimated form. In the novel Richard says Barrett stands for “ease and comfort” (51), whereas Richard can only promise “I’ll do all I can to make you happy” (62). If the end of Losey’s film makes little sense, it is because while both film and novella show Tony’s moral disintegration, Maugham’s work shows that disintegration as resulting from the denial of his true self in favor of that which is conventional and easy. Losey’s film, on the other hand, shows it resulting from Tony’s faltering attempts to surrender to his true sexual identity. Substituting Susan for Richard not only changes the value of Barrett in the story, it changes the value of homosexuality.

The pimping of Vera makes more sense in the book than than in the film, where we are to understand that she is the vicarious means through which Hugo and Tony can indirectly consummate their own passion. (By each being with the same woman they are sorta, kinda with each other.) But, then, doesn’t such a change tend to simply reinforce the audience’s homophobic stereotypecs and suggest that what so many viewers find creepy about the film was, in fact, its subject matter rather than its representation of it? Are Losey and screenwriter Harold Pinter participating in cultural sexual panic by making the boogie man (and not just his victim) gay? I would like to think that Losey’s own experience of being blacklisted in Holllywood would make him sympathetic to people in art (or life) who are ostracized and that the creepy visual iconography of the film is not so much indicative of his revulsion at Tony’s repressed sexuality but at a world in which the fear of it creates an internalized self hatred.

I would like to think that, but I’m going to have to watch some more of Losey’s films before I’m ready to say for sure.