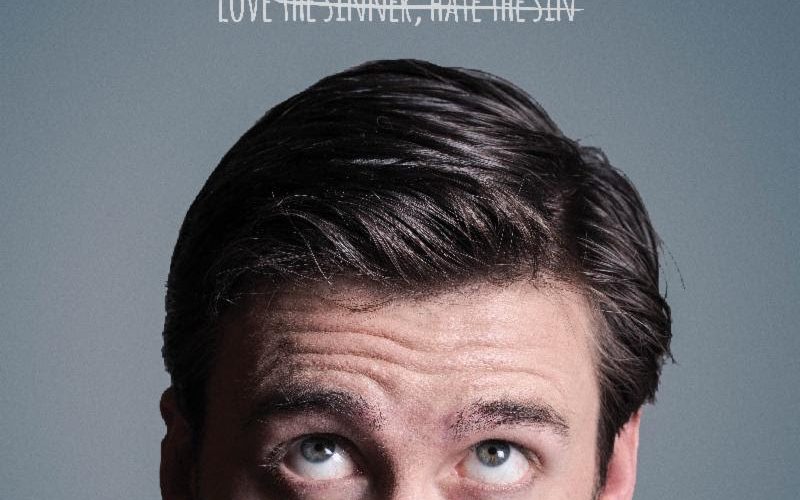

At the End of the Day (O’Brien, 2018)

Near the conclusion of At the End of the Day, a kind Christian woman offers up the film’s coda. It’s not, as you may suspect from the film’s advertising that Christians should love gay people. Protagonist Dave Hopper (Stephen Shane Martin) has pretty much already arrived at that conclusion on his own. It’s that Dave and Christians like him have fundamentally misunderstood the Bible. There are a lot of things in the Bible that she doesn’t understand, but unlike Dave, she gets what it is about: love.

That I am simpatico with the film’s cultural work makes this scene go down easy, but it doesn’t quite blind me to the fact that her approach to interpreting the Bible isn’t really any different from that of the homophobic dean (Tom Nowicki) at the Christian College where Dave works. Both characters avoid rather than confront questions about their exegesis by essentially claiming that the overall thrust of the Bible’s position is clear and that such clarity justifies ignoring the problematic aspects of passages that seemingly conflict with their views or the practices that stem from them. Yet as similar as both characters are at waving away the parts of the Bible that are inconvenient to their respective positions, the film seems oblivious to this parallel, presenting one character as close-minded and the other as salt and light proclaiming the simple truth.

Let me hasten to add, though, that this card-stacking doesn’t diminish the film’s value as an artist’s personal testimony, it just makes it less decisive than it thinks it is. That the protagonist is a fill-in for writer/director/producer Kevin O’Brien is freely conceded in the film’s promotional materials, where he says: “As my faith and views changed, I was compelled to create my first film about the tensions between the church and the LGBTQ communities. I felt an obligation to call out the misinformation that is taught in many churches at the same time I offer a hug to the LGBTQ community, specifically to those youth who have faced religious rejection.”

The plot follows O’Brien’s avatar, a Christian counselor named Dave Hopper, who takes a position at a Christian college and agrees to infiltrate an LGBTQ support group in order to sabotage their fund-raising plans so that the college can buy a local property that is earmarked to be donated for a homeless shelter.

The plot follows O’Brien’s avatar, a Christian counselor named Dave Hopper, who takes a position at a Christian college and agrees to infiltrate an LGBTQ support group in order to sabotage their fund-raising plans so that the college can buy a local property that is earmarked to be donated for a homeless shelter.

When the film misfires, it usually does so because it seems unsure of its audience and thus can’t settle on a particular voice or position. O’Brien’s quote suggests this is directed towards gay viewers, but I am skeptical that they will be invested in a story that is essentially about a straight, conservative Christian’s dawning awareness that — stop the presses! — evangelical Christians too often reject them. Only once, in a montage where Dave half-heartedly tries to exacerbate tensions between members of the group, does the film fleetingly acknowledge differences within the LGBTQ community. How long has this group been active, Dave asks its token transgender member, and there are still no unisex bathrooms?

The rather generic nature of the gay characters is partially a function of the film’s genre, but I suspect it is more a function of O’Brien’s background informing his writing. The cinema-verite type interviews with gay teens telling their stories have a lot more punch than the staged fight that one of the characters inexplicably has on his cell phone to play for Dave in order to show him just how toxic his teaching is.

But almost all of the places where the film lands its punches are in scenes where Christians talk to other Christians or straights to other straights. A town hall leader sarcastically dismisses a Christian woman with the barb that she is sorry that gays have “undermined the sanctity of your third marriage.” In perhaps the film’s best moment, a young girl from the college expresses confusion about Dave’s siding with the gays, insisting that the anti-gay position is what he “taught” them.

Maybe I like that scene because I’ve taught at a Bible college before, and I’ve had plenty of people quote Mark 9:42 to me. (Tangent, why does no one ever note that the preceding verses are about disciples deciding who is Christian and who isn’t?) Or maybe it is because it is the seed of a stronger movie, a subversion of God’s Not Dead, that I would have been happier to see–one that truly wrestles with the relationship between Biblical truth and human teaching and whether one can ever be free of the other.

Looking back over what I have written, I realize that I probably sound more critical of the film than I feel. I suspect that stems from overcompensating so that I don’t fall into the trap of giving a free pass to films whose agenda I agree with when I would gladly point out the flaws in arguments that were similarly used to support causes I found odious. But while fairness demands I acknowledge those flaws, it also demands that I concede there is some genuine talent at work here. O’Brien and Nowicki avoid turning the Dean into a cardboard monster. He is oddly the more sympathetic for genuinely believing in the righteousness of his path, and the scene where he parts ways with Hopper is surprisingly but rightly played with more sadness than sanctimony. There’s also a professional ease in O’Brien’s direction. The light, composition, and screen density of the dean’s office in comparison to that of the support group visually supports the film’s themes. The use of mise-en-scene is not particularly groundbreaking, but it’s there, and it illustrates a professional competence and confidence that is often lacking in “Christian” films.

At The End of the Day is sort of like a cinematic safety-pin that gay-friendly Christians can wear, ostensibly to let that put-upon group know they are safe to talk to but really to differentiate themselves from the practices and attitudes of other Christians with whom they disagree. It’s not a game changer, but it’s a step in the right direction.